WARNING: This article contains graphic descriptions of child sexual abuse. Reader discretion is advised.

Remember the self-avowed LGBTQ+ activists accused of sexually abusing their adopted sons? Long after the mainstream media dropped the shocking story, refusing to touch it with a ten-foot pole, Townhall has been the only outlet closely covering the Zulock case hearing-by-hearing, never missing a motion or a court filing.

To recap, William Dale Zulock and Zachary Jacoby Zulock, frequent faces at the Atlanta Pride Parade, are accused of forming a child-prostitution ring in the Atlanta suburbs. The couple was arrested overnight on July 27, 2022, allegedly in the midst of amassing pedophile members, whom they met off of the gay hook-up app Grindr and to whom they would pimp out their elementary-aged children.

Zachary (left) and William (right) Zulock at the Atlanta Pride Parade, carrying rainbow "Born This Way" flags (Zachary Zulock | Instagram)

Zachary (left) and William (right) Zulock at the Atlanta Pride Parade, carrying rainbow "Born This Way" flags (Zachary Zulock | Instagram)

Among the slew of child sex crimes they're facing, the Zulocks are charged with producing and distributing "homemade" child pornography with the two boys they had adopted locally through a Christian special-needs adoption agency, All God's Children, Inc. The now-defunct business prioritized placing children who have "waited the longest" for a family. Many of the kids already came from broken homes. Others were either older or part of a sibling pair bonded together. Some suffered from physical, mental, or behavioral challenges.

Recommended

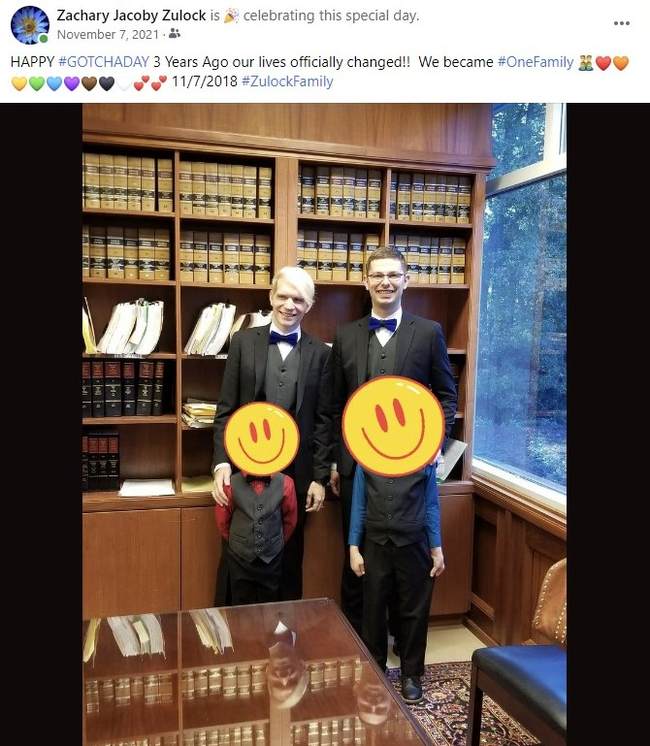

In 2018, the same-sex newlyweds apparently passed the "faster than expected" adoption process "with flying colors," despite the fact that one of the adoptive fathers was previously accused of raping a young boy in another child rape case from years ago. Within months of the children moving in with the alleged child predators, Georgia's courts made the "forever family" official in early November of that year.

A photograph from the judge's chambers on the day the Zulocks officially adopted the two boys (Zachary Zulock | Facebook)

A photograph from the judge's chambers on the day the Zulocks officially adopted the two boys (Zachary Zulock | Facebook)

The biological brothers, reportedly born to heroin addicts, were only ages 6 and 8 when the years-long sexual abuse allegedly started in late 2019. According to court documents obtained by Townhall, the children were "routinely" raped "at least once a week." Per the probable cause affidavit, William and Zachary confessed to anally penetrating both boys, forcing the two children to perform oral sex, and doing the same to them. The men acknowledged that the boys would cry out that it hurt when they were being abused, but they'd walk them through "how to handle the pain."

The older child, who sustained physical injuries from being brutally raped, told police that Zachary, the cameraman, would be in bed recording when William was abusing him. "I'm going to f**k my son tonight," Zachary allegedly bragged to potential clients, instructing them to "Stand by." He'd send unsolicited messages describing "what he would do to his son," the Walton County Sheriff's Office says.

The Zulock "family" on vacation in 2019 (William Zulock | Instagram)

The Zulock "family" on vacation in 2019 (William Zulock | Instagram)

Authorities were ultimately tipped off by a Snapchat video Zachary allegedly filmed at home in one of the bathrooms. The pornographic clip depicted "an adult male penis was repeatedly being put in the mouth of a prepubescent male." A ball gag, a blindfold, and bindings were visible in the video, says the search warrant executed on the Zulock house, the so-called "Gayest Place in Town," according to a welcome mat that adorned the front entryway. Jurassic Park footy pajamas found in the child's bedroom and a DVR set taken from the in-home "theater room" were on the laundry list of items seized and stored away as evidence.

"Our business is our business. What happens in our home, stays in our home," the men allegedly told the boys. The children said that they were threatened each time they left the house and directed not to tell anyone about the sexual abuse or "there would be consequences."

"Our business is our business. What happens in our home, stays in our home," the gay activist couple allegedly told their sexually abused sons.

— Mia Cathell (@MiaCathell) January 18, 2023

LGBTQ-pride decor littered the Zulock mansion. Placed at the entrance: a rainbow Mickey Mouse and a "Gayest Place in Town" welcome mat. pic.twitter.com/G0svd1Ikks

In a midnight search-and-rescue mission the morning of July 28, 2022, an armed SWAT team descended on the property, tackling Zachary to the foyer floor and busting William butt-naked in bed, as the couple recounted in recorded jailhouse tapes shared with Townhall. Both boys are back in foster care.

If convicted, the couple faces multiple life sentences. Though there's been much talk about a trial since the summer 2022 arrests, the Zulock case has seemingly ground to a halt, except for some status conferences that have been few and far between.

Here's what we know so far:

Judge Jeffrey L. Foster, who's presiding over the proceedings, is eyeing the end of August to set a tentative trial date.

The next hearing, another status conference after several sprinkled sparingly over many months, is slated for Wednesday, June 26.

"We will be six weeks out from about the ballpark time of the end of August—when I am looking at a trial calendar," Foster said.

At a March 20 status conference, Foster mentioned scheduling the June hearing in order to navigate setting up a special session for the Zulock case. "I'm plotting—I mean planning now," Foster said.

The purpose of this previous proceeding was to decide what to do with the defense's special demurrer.

A special demurrer, a.k.a. a motion for more definitive dates, challenges the charges by asking for additional details or specificity, such as specific dates of when the crimes were committed.

Currently, each charge against the Zulocks alleges an "expansive" date range of when the sexual abuse took place; therefore, that's too "broad" and "practically impossible" to prepare a defense, including raising an alibi, the Zulocks are arguing in an effort to toss out the 17-count indictment brought by a Georgia grand jury.

The charges are as follows:

- Count 1: Aggravated sodomy (Dec. 30, 2019 – July 28, 2022)

- Accusation: Performed oral sex on D.Z.

- Count 2: Aggravated sodomy (Dec. 30, 2019 – July 28, 2022)

- Accusation: Forced D.Z. to perform oral sex

- Count 3: Aggravated sodomy (Dec. 30, 2019 – July 28, 2022)

- Accusation: Anally raped D.Z.

- Count 4: Incest (Dec. 30, 2019 – July 28, 2022)

- Accusation: Sodomized D.Z., son by adoption

- Count 5: Aggravated sodomy (Dec. 30, 2019 – July 14, 2022)

- Accusation: Performed oral sex on J.Z.

- Count 6: Aggravated sodomy (Dec. 30, 2019 – July 14, 2022)

- Accusation: Forced J.Z. to perform oral sex

- Count 7: Aggravated sodomy (Dec. 30, 2019 – July 14, 2022)

- Accusation: Anally raped J.Z.

- Count 8: Aggravated child molestation (Dec. 15, 2021 – July 28, 2022)

- Accusation: Anal rape resulting in the injury of J.Z.

- Count 9: Aggravated child molestation (Dec. 15, 2021 – July 28, 2022)

- Accusation: Oral sodomy of J.Z. as to Count 6

- Accusation: Oral sodomy of J.Z. as to Count 6

- Count 10: Aggravated child molestation (Dec. 15, 2021 – July 28, 2022)

- Accusation: Oral sodomy of J.Z. as to Count 5

- Count 11: Incest (Dec. 30, 2019 – July 28, 2022)

- Accusation: Sodomized J.Z., son by adoption

- Count 12: Sexual exploitation of children (Dec. 30, 2019 – July 28, 2022)

- Accusation: Sexually exploited D.Z. for the purpose of producing CSAM

- Count 13: Sexual exploitation of children (Dec. 30, 2019 – July 28, 2022)

- Accusation: Sexually exploited J.Z. for the purpose of producing CSAM

- Count 14: Sexual exploitation of children (Dec. 30, 2019 – July 28, 2022)

- Accusation: Produced, possessed, and distributed child pornography depicting the sexual abuse of D.Z.

- Count 15: Sexual exploitation of children (Dec. 1, 2019 – July 28, 2022)

- Accusation: Produced, possessed, and distributed child pornography depicting the sexual abuse of J.Z.

- Count 16: Pandering for person under 18 (Dec. 30, 2019 – July 28, 2022)

- Accusation: Prostituted J.Z. to co-conspirator Hunter Clayton Lawless

- Count 17: Pandering for person under 18 (Dec. 30, 2019 – July 28, 2022)

- Accusation: Prostituted J.Z. to co-conspirator Luis Vizcarro-Sanchez

As explained by Brody Law Firm, a boutique Atlanta-area criminal defense firm specializing in sex offense allegations, when "the accusers" are children, kids tend to have difficulty recalling dates or pinpointing time periods, especially if the victims are in the earlier stages of development. For example, a child may say that the sexual abuse happened "when I was in 2nd grade." The local law firm advises that the special demurrer is an "indispensable tool" to defend against accusations involving young children.

While Georgia law does allow for the prosecution to allege that the crime occurred between two dates, the timespan must be narrowed down as much as possible. If the evidence shows that the state did not do so (i.e. failing to sufficiently particularize the dates), then the indictment could be successfully dismissed by a special demurrer. The defendant would subsequently be entitled to an evidentiary hearing requiring the prosecution to prove that it cannot narrow down dates.

The government can re-indict the case, though, if the indictment is quashed by the court. However, this could afford the defense an opportunity to demonstrate the case's weakness, ultimately leading to a dismissal of the charges. In the event that the case is indicted again, and the second indictment is found defective, the government is barred from further prosecution of the defendant, per state statute.

The indictment, as it is, is sufficient statutory language-wise and explains exactly what the sexually abusive acts were, Foster ruled. "It doesn't just say an act of sodomy. It specifies whose mouth or whose rectum, whose sexual organs."

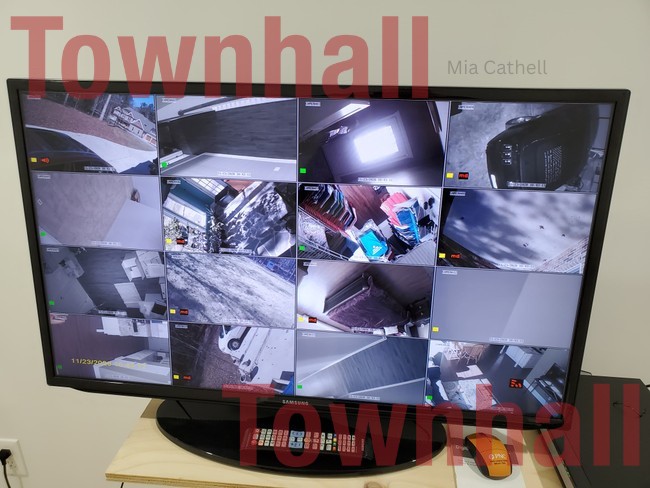

At this time, they were discussing whether or not to seek a re-indictment of the criminal charges with more counts added on after the defense's request for specific dates sparked a forensic investigation into the surveillance system that the Zulocks had installed in the interior of their home.

A formidable four terabytes of data, which investigators are continuing to comb through, was extracted from the 16 security cameras stationed all over the house in every single room. The cameras were recording 24 hours a day, seven days a week, capturing everything, including the sexual assaults. "They are all on video filmed throughout multiple rooms in the house," the prosecution says.

A TV transmitting a live feed from inside the Zulock house. Of the 16 surveillance cameras positioned all over the premises, one of the cameras captured an aerial angle of a mattress. (Zachary Zulock | Facebook Messenger)

A TV transmitting a live feed from inside the Zulock house. Of the 16 surveillance cameras positioned all over the premises, one of the cameras captured an aerial angle of a mattress. (Zachary Zulock | Facebook Messenger)

So, the prosecution can now specify "hundreds of allegations," matching the metadata to timeframes, as the defense unwittingly welcomed.

As of March, the prosecution was waiting on an official report from the Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI)'s crime lab, where the forensic examination is underway, but had only received a four-paragraph summary of the GBI's findings.

On May 20, the prosecution provided the defense with the GBI Cyber Crime Center (GC3)'s 18-page investigative report detailing some of what was discovered in that extraction.

In court, the prosecution indicated that these are individual write-ups and that further reports are forthcoming spanning "hundreds of pages."

Astounded by the volume of data, William's defense attorney John E. Haldi said, "I had to look up terabytes on Google. One terabyte is, depending on the quality of the video, roughly the length of anywhere between 100 to 150 two-hour movies at the movie theater." In accordance, Haldi asked that the GBI provide some assistance with cross-referencing dates to timestamps of the security footage to help mount his defense.

"They aren't obligated to do that," Assistant DA Lacey Majors of the Walton County District Attorney's Office countered. To which, Haldi responded, "Then I need months to review it."

The dispute prompted a fed-up Foster to interject.

"Here's what's going to happen. We are going to trial in August. So either you are going to trial on a new indictment that has, as I understand it, hundreds of counts, because now that they can specify dates and timestamps, they will re-indict [...] or do you want time to process that evidence and specifically focus on the smaller 17-count indictment that is pending now," Foster told Haldi.

Majors clarified that the charges, as they stand, stem from child pornographic photographs and videos—taken primarily on Zachary's iPhone—that are presently in the DA's possession. A folder, labeled "US," was allegedly found on Zachary's cell phone containing videos of William sexually abusing their one son.

"Those things have been available for inspection for two years..." Foster added. "I think we are right at two years from the actual arrest."

Turning it on the other party, Haldi said that throughout the two-year wait, the prosecution has not been able to provide exact dates.

"It has taken them [the investigators] that long because your client saved that much data," Majors fired back.

Foster reiterated to Haldi that the GBI only conducted its labor-intensive, months-long analysis because he requested that the state be specific in its charging instrument. Accordingly, the state is then inclined to charge each instance of sexual abuse as investigators find them in the footage, Foster explained.

As they await the GBI's reports, Haldi was instructed that the digital material can only be seen in a secured location on-site.

Incensed by the stringent stipulations, an aggravated Haldi said, "I have to do it in their offices on their schedule," harping on how reviewing the exorbitant quantity of evidence could take up a significant amount of his time.

"Well, that is the law," Majors stated matter-of-factly.

"When the law is contrary to my client's interests, I have to stand up for that," Haldi replied.

"We can't create and copy child pornography for you," Majors said.

Pivoting, she said, "Mr. Haldi, we have evidence that you have never asked to come see."

"That's not true," Haldi rebutted. "I have been to your office several times. I have never asked to come see it? Good gravy!"

Foster, weighing in, asked Haldi if he actually inspected the evidence himself.

"Three times, judge," Haldi answered immediately. He recounted sifting through a three-ring binder containing still images and delving into the contents of a number of thumb drives. "I have got to make sense of it myself again in your office at your disposal," Haldi griped.

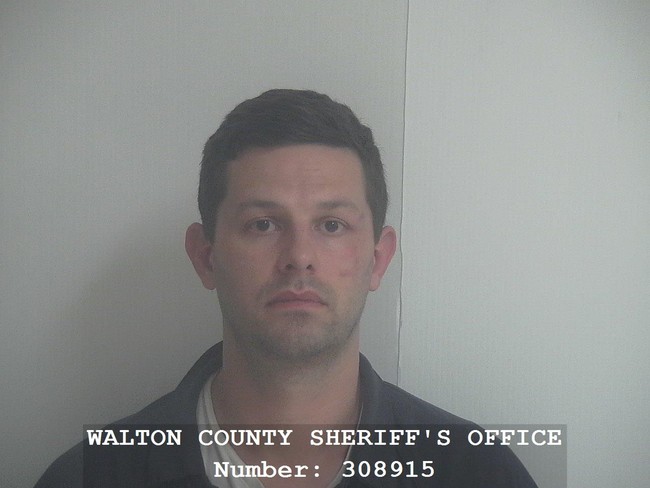

Zachary Zulock's mugshot (Walton County Sheriff's Office)

Zachary Zulock's mugshot (Walton County Sheriff's Office)

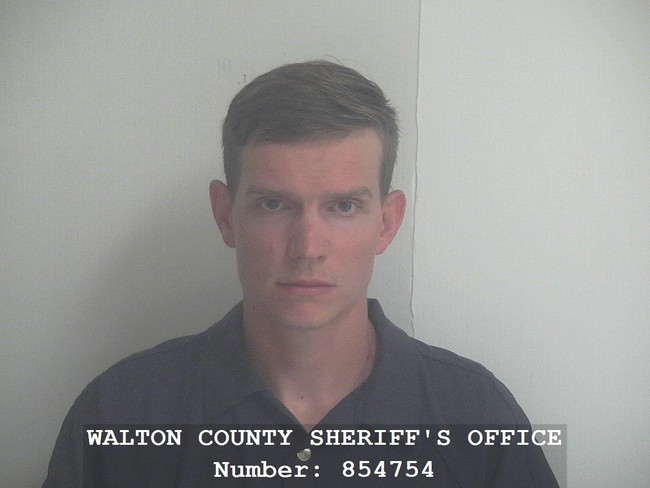

William Zulock's mugshot (Walton County Sheriff's Office)

William Zulock's mugshot (Walton County Sheriff's Office)

Foster said that Haldi did not have to announce whatever his plans are that very day—that is, his decision to continue with the demurrer or not.

"If we are going forward on a demurrer in this case [...] we will indict..." Majors declared. "There will only be more counts, not less. I can say that," Majors said.

"Your Honor, I'm getting these implicit threats: 'Hey, if you look at the evidence, we're gonna charge your client with more. We're gonna try to send him to jail for 100 life sentences instead of 20' [...] In all my years at the bar, I have never been presented with that dilemma [...] I have never had the state say, 'I have hundreds and hundreds of hours of evidence. Good luck finding it.' I have never had that," Haldi said.

Foster said in his 17 years of criminal defense, he never had a prosecutor hand him "a handwritten map." In the past, he's been given a file or a data dump or a printout "that thick," Foster said, gesturing with his hands. "It is a pain," he conceded, adding that he used to have to drive to GBI's headquarters in Augusta.

Again, Haldi asked that "benchmarks" be highlighted in the GBI's reports so that he can efficiently examine the evidence. "I am happy to comply with that. But if they dump the equivalent of 600 full-length movies on me and say, 'Figure it out yourself,' you can bet I'm going to object to that."

This week, we will see where the case stands and how much of the evidence Haldi has been able to "plow through," as Foster phrased it. The Alcovy Judicial Circuit judge told Haldi he can submit a waiver in writing, if he does decide to drop the demurrer.

Haldi had appeared via video conference instead of in person. The case's slow-walking can be blamed, in part, on Haldi's prolonged leave of absence lasting from August through November 2023, which he had designated on the court calendar for physical therapy and rehabilitation. Last year, Haldi fell and broke his hip, rendering him immobile and unable to drive anywhere, including to the Walton County courthouse.

As Zachary was transported out of the holding room by the bailiff and William was ushered in, Foster bantered with Haldi for a bit about his recovery. "You'll hear the metal detector when I finally do make it to court," Haldi joked. Piling on, Foster mentioned how he has a pacemaker and oft-experiences trouble going through security at the airport.

"I've been groped in every airport and courthouse in Georgia," Foster joked offhandedly at the March hearing in the sprawling child sexual abuse case.

Majors laughed, observing that the court stenographer didn't transcribe that tidbit. "You didn't take down that he's been groped in airports?" she asked. "Really, I've been groped in more courthouses than I have in airports," Foster continued.

Although Haldi's "slightly more mobile" now, propped up haphazardly by a walker-and-cane combo, his lack of mobility, coupled with cardiac issues, is still interfering with his work defending William.

"Mr. Haldi, let's be realistic. Because of the nature of the information you got to review," Foster worded it euphemistically, "your mobility is currently hindering your ability to get out here. I am certainly not insensitive. In fact, I am rather sympathetic to that." Previously, the judge joked about Haldi and him crossing paths at Emory's electrophysiology clinic.

In the interim, Foster instructed Haldi to keep the court "in the loop" between then and when they reconvene Wednesday.

For half a year, Haldi was unreachable; even his client couldn't get ahold of him. "We are just not sure if he is even representing, Mr. [William] Zulock," the prosecution said around Christmastime. At a December 20 status conference, after his leave of absence elapsed, the ever-inaccessible Haldi had "not been in communication with anyone," not responding to emails or phone calls from prosecutors. They tried texting him and leaving voicemails to no avail.

Appearing virtually, William Zulock wore a black COVID-19 mask and a navy-blue Walton County Jail jumper. He shook his head repeatedly when the prosecution recited the slew of charges leveled against him. (March 20, 2024 | Townhall Media)

Appearing virtually, William Zulock wore a black COVID-19 mask and a navy-blue Walton County Jail jumper. He shook his head repeatedly when the prosecution recited the slew of charges leveled against him. (March 20, 2024 | Townhall Media)

William hadn't heard from him either and neither had his parents, who are footing his legal fees. "I think they want to fire him," William, unaware of Haldi's medical incapacitation, told Foster. Saddled with the accruing court costs, William's side of the family has spent at least $50,000 on William's criminal defense.

Haldi's indisposed state has left Foster unwilling to rule on anything substantive without William having proper representation first. "We're not going to let it fall through the cracks," Foster vowed to William.

Also absent from the courtroom was Zachary's court-appointed defense attorney, Reginald L. Winfrey, who just so happens to serve as general counsel for New Birth Missionary Baptist Church, a black megachurch whose senior pastor has publicly spoken out against same-sex marriage and preached that "homosexuality is a sin." Notably, Winfrey also works at his wife's law firm, the Law Office of Earnelle P. Winfrey, who is a deputy district attorney in Fulton County DA Fani Willis's administration, specifically spearheading her Human Trafficking and Internet Child Exploitation Unit.

Prior to the mid-March proceeding, Winfrey informally sent the prosecution team a lengthy text message in a group chat, which Haldi was a part of, indicating he's "not prepared to announce ready for trial" because he also intends to come in and physically review evidence.

Winfrey, who adopted Haldi's motion, has since withdrawn from the special-demurrer request in lieu of an impending wider-ranging indictment.

Back at a May 17, 2023, motion hearing, Foster addressed a flurry of pre-trial filings.

There, Foster granted the state's motion to sever the co-defendants, who were jointly indicted.

Objecting to the severance motion, Winfrey implored that Foster allow them, the Zulocks, to go to trial together. Winfrey cited no legal basis, other than claiming that the alleged child rapists are asking out of concern for the abused boys being re-traumatized.

"My client would prefer not to put the children on the stand twice," Zachary's counsel claimed.

Haldi agreed. "We also have no desire to have the children go through two separate trials, so I parrot what Mr. Winfrey said."

Foster noted that under the child hearsay statute, the defense attorneys may be the ones to control whether the children will have to testify more than once. The kids could also offer testimony on video to "minimize impact," Foster mentioned.

As for spousal privilege, Foster decided it's best deferred until the surveillance footage's metadata is returned.

Self-described "#partnersincrime for life" (Zachary Zulock | Instagram)

Self-described "#partnersincrime for life" (Zachary Zulock | Instagram)

Foster did permit the prosecution to compel the Zulocks to testify against one another under grants of immunity, which means nothing that they say on the witness stand can be used against them in their own individual trials. Even though they're immunized against self-incrimination, they are still subject to penalties for committing perjury and making false statements.

The prosecution intends to call on William as a witness in Zachary's trial and vice versa, though it's not yet known who will be tried first. Their testimonial statements to police "clearly implicate" the other defendant, the state says.

Haldi, unprompted, questioned the judge: "Would, Your Honor, anticipate recusing yourself in a second trial?"

"No," Foster retorted tersely.

"I simply don't know how you could un-hear some of the things," Haldi ventured further.

"Well, I am not a fact-finder. So, no. I would not recuse myself because I will not be making any findings of guilt or innocence," Foster said, presuming they're not bench trials and the cases go before separate sets of 12-person juries.

To ensure a fair and impartial jury, out of "an abundance of caution," Foster signed a gag order restricting extra-judicial statements following Townhall's publication of the couple's out-of-court commentary. The men had enthusiastically blabbed about the case to a relative, who then captured the confessions in a series of tell-all texts, sent on jail-issued tablets, and phone calls from behind bars.

Immediately after they were warned against speaking about their criminal case to third parties, the #Zulock co-defendants—left dumbfounded by the prosecution dangling the threat of a gag order—both blabbed anyways in spite of the judge's advice.

— Mia Cathell (@MiaCathell) February 21, 2023

Read the tell-all jail texts 👇 pic.twitter.com/QRulPCtBBE

However, the court order only applies to attorneys and law enforcement officials. It's not a restraint on members of the media or third parties, Foster clarified, as they are protected under the First Amendment.

At issue was also Zachary's string of confessions in police custody and whether he actually invoked his constitutional right to counsel. Winfrey, who filed a motion to suppress his incriminating statements, argued that his admissions were inadmissible.

A portion of Zachary's police interrogation was played in court, around the one-hour mark.

According to the videotape of Zachary's in-custody interview, he said:

"So, I guess I need a lawyer first then."

"I didn't say I am unwilling. I just asked for my lawyer because you mentioned it at the very very beginning."

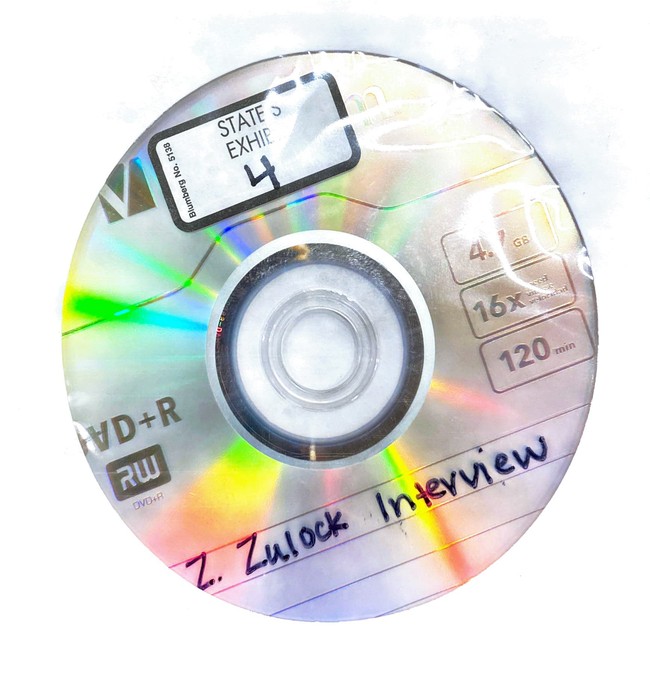

A DVD of Zachary Zulock's police interrogation (Walton County Superior Court | State's Exhibit #4)

A DVD of Zachary Zulock's police interrogation (Walton County Superior Court | State's Exhibit #4)

Foster noted that the Miranda warnings were read beforehand. The issue came down to whether there was a "clear invocation of counsel" after Zachary previously waived the right to legal representation.

DA Randy McGinley cited a Georgia case where the defendant similarly said he "might need a lawyer." Comparing the cases, McGinley argued that Zachary, too, made an ambiguous assertion. Next, the chief prosecutor pointed to a 2019 Georgia Supreme Court opinion and quoted the ruling: "When a Defendant makes an equivocal reference to counsel [...], interviewing officers are not always required to clarify their request but they can." That decision cited a U.S. Supreme Court case, which says, "Of course when a suspect makes an ambiguous or equivocal statement, it would often be good practice for the interviewing officers to clarify whether or not he actually wants an attorney." That was the procedure followed in the Zulock case, McGinley said. The detective asked Zachary follow-up questions for clarity's sake, such as "Do you want to talk to us?" In response, Zachary said he was not "unwilling" to talk.

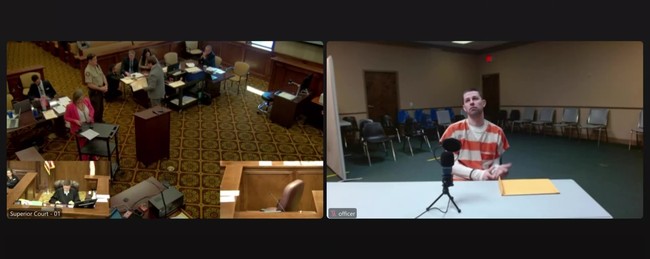

Zachary Zulock, wearing a striped orange-and-white Barrow County Detention Center uniform, sat separately in a holding room designated for locked-up defendants to tune in. He remains detained out of county under "maximum" security. (March 20, 2024 | Townhall Media)

Zachary Zulock, wearing a striped orange-and-white Barrow County Detention Center uniform, sat separately in a holding room designated for locked-up defendants to tune in. He remains detained out of county under "maximum" security. (March 20, 2024 | Townhall Media)

Since it's a constitutional matter, not a question of state statute, McGinley moved to reciting case law in other jurisdictions beyond Georgia. In a 2022 Illinois case, a defendant was asked whether he wanted to speak to detectives or an attorney. "An attorney, I guess," the defendant said. The court deemed the defendant's statement equivocal. Out of Texas, in a 2016 appeal case, the defendant said, "I guess I'd like a lawyer." The court found that that was equivocal.

"Wondering about an attorney is not invoking your right to an attorney and wanting to stop questioning," McGinley argued, urging Foster to find that Zachary's statements were voluntarily made.

Winfrey relied on Wheeler v. State, a 2011 Georgia case involving aggravated sexual battery, cruelty to children, and child molestation. The defendant said, "You know, I'm not trying to be hard to get along with, but the seriousness of my charges and everything, I need to discuss it with a lawyer before I, you know, talk to you." He was convicted at trial and the appellate court affirmed it. The case went all the way to the state's Supreme Court, which reversed it.

"Well, if I recall Wheeler, the context of the statement in Wheeler was not an expression of a willingness or unwillingness but rather that he was not trying to be difficult or hard to get along with," Foster replied.

Rejecting Winfrey's comparison, Foster found the Zulock case akin to Willis v. State. In that case, the state's Supreme Court determined the invocation was not clear and was, at best, equivocal. The detective asked, "Do you want an attorney before you talk to us?" Willis, the defendant, said, "No, I'm saying I don't have any problem answering any questions, but I still do want an attorney." There were these "countervailing things, which is the equivocation," Foster remarked.

Applying it to the Zulock case, Foster said Zachary asked, not stated decisively, "So, I guess I need a lawyer first then?" That was an "equivocal question," Foster ruled, "not an invocation." He was advised by the detective, "That's your choice." They then talked until Zachary said, "I didn't say I am unwilling." Of Zachary's second statement, Foster heard it as, "I just asked about my lawyer because you mentioned it at the very very beginning." Even if he had said, "I just asked for," that implied past tense, Foster said. "He sandwiches it between two statements that he is willing to talk [...] two expressions of a willingness to talk, and the only other reference was a question about 'I guess I need.' This was not a clear, unambiguous invocation of right to counsel."

Foster found that Zachary was advised of his Miranda rights, expressed that he understood them, and that he voluntarily waived them. His statements were equivocal and, "really, more questions," Foster said. Therefore, his admissions are admissible at trial.

Editor's Note: Townhall's investigative reporting exposing the disgusting, depraved behavior of the left would not be possible without the support of our VIP members.

Join Townhall VIP and use promo code INVESTIGATE to support the vital work of Mia Cathell and help us continue to shed light on the darkest parts of the radical left.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member