First, crises unite or divide. How society responds is as much about society as leadership. Historian Wayne Cole described emotions running hot pre-WWII politics. “Individuals on both sides found it increasingly difficult to see opponents as honest people who happened to hold different opinions.”

Accordingly, “attacks on both sides became more personal, vicious and destructive” and “it became easier to see one’s adversaries not just as mistaken but as evil, and possibly motivated by selfish, antidemocratic, or even subversive considerations.” That’s a dead end. We learned, let’s not forget.

Second, beating a crisis is harder than talk. Even when America goes to a “war footing,” time is needed for retooling. Gaps occur. As retooling took time in WWII, making car plants produce ventilators takes time. Getting resource inputs for more masks and robes takes time.

In July 1941, as we prepared for war and helped Great Britain, everything turned cold molasses. Historian Lynne Olsen, writing in Those Angry Days, describes production as “paltry” when “compared to the vast demands and needs …” Incredibly, of $7 billion appropriated in March 1941, only two percent reached Britain by July. Government is slow. Private retooling takes time.

Even so, America today is nimble. On March 24th, Ford, General Motors and General Electric announced a pivot to making respirators and ventilators, not cars, refrigerators and dishwashers.

Third, foreign actors exploit our disunity. World War II offers countless examples. Germany wanted to keep the United States out of war, so Germany encouraged Americans who opposed the war. Foreign actors are doing the same now. China reinforces anti-Trump sentiment, cites US sources to blame the virus on us.

Recommended

Likewise, vocal in opposing FDR, Americans inadvertently helped opponents. FDR – a Democrat who moved with method – criticized those who had criticized him mid-crisis.

Said FDR, opponents “were not only wrong, they were contributing mightily to apathy and disunity, thus jeopardizing national survival.” Then as now, they sought to wrest power in the name of “debate.”

FDR saw it very differently. He said their efforts reinforced “clever schemes of foreign agents” intended to “create confusion, public indecision political paralysis, and eventually a state of panic.” Presidents have a tough job; seeking unity is part of it. Patriots should weigh that into their thinking.

FDR’s words are 75 years old but sound fresh. Creating disunity is easy, repairing it hard. As the adage goes: “It takes a seasoned carpenter to build a barn, but any jackass can kick it down.” We need more carpenters – along with more masks, gowns and ventilators.

Fourth, post-crisis critics abound, just expect it. When World War II was over, many leaders – including General George C. Marshall – were interviewed. They were tough on Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

While FDR empowered field commanders, as Trump has done, FDR was accused of not moving fast enough. Critics said he should have accelerated war- footing, engaged faster, cracked the whip to ramp up supplies, recognized America needed to save Europe.

Marshall was a wartime supporter yet became a critic. In retrospect, he saw things differently. Marshall told his biographer if the United States had begun rearming in 1939 – not waited – the decision could have “shortened the war by at least a year” saving “billions of dollars and 100,000 casualties.” Perhaps. But after the dust settles, everyone seems to know what might have settled it faster.

After a crisis, even those part of solving the crisis blame others for insights no one had. Part of preserving unity is remembering events emerge quickly, often without warning, and for a while are hard to control.

Think about it. If diplomacy had taken a different course after World War I, or if European leaders had not overlooked Germany’s rearmament, or if France had not believed the Maginot Line, or if... You get my point. What matters is less what might have been, than good-faith leadership in the moment.

The corollary: Crises often reflect collective unpreparedness and the sudden appearance of an unforeseen event. That is seldom the fault of one person.

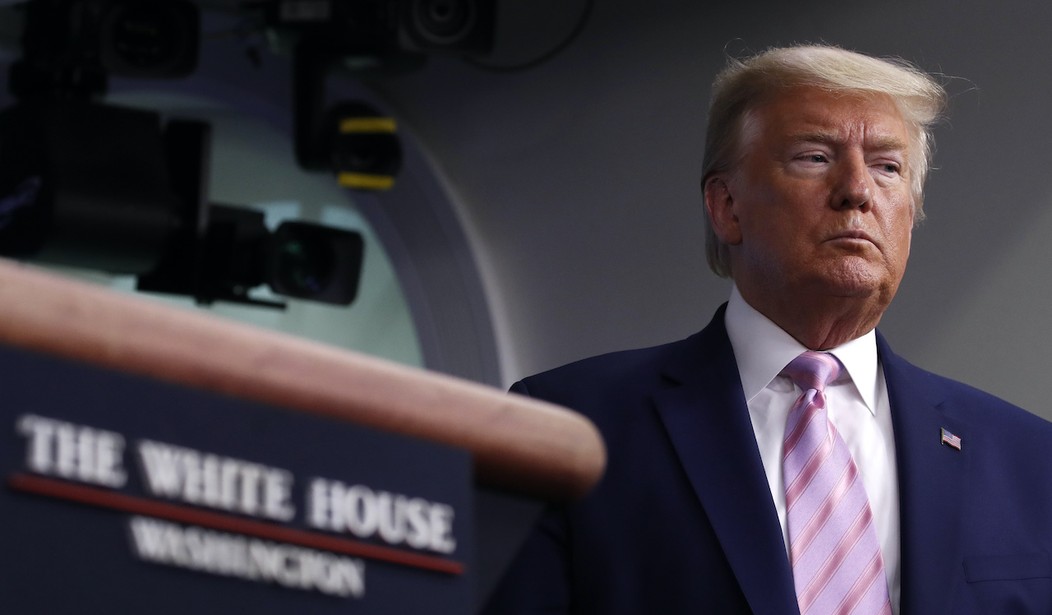

If George Marshall could fault FDR, expect attacks on Trump for not being omniscient. Predicting what already happened is easy, but tough calls mid-crisis are hard. Trump is imperfect, but he is leading.

Net-net, the old lessons apply today. Unity is harder than disunity – work toward unity. Confronting crises is harder than talk – be the solution. Foreign exploitation lurks – be circumspect. And as the cloud lifts, critics multiply. Getting through this crisis will take effort. Let’s pull together – not apart.

Robert Charles is a former assistant secretary of state for President George W. Bush, former naval intelligence officer and litigator. He served in the Reagan and Bush 41 White Houses and is spokesman for the Association of Mature American Citizens (AMAC) a 2.1 million-strong, non-partisan group for Americans 50+.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member