In spring, hearts turn to baseball, so stay with me, please, as I show you how some supposedly objective social science research is not worth a broken bat or a coming-apart-at-the-seams ball.

Imagine a social scientist, with a large research grant, studying baseball players drafted each year by the 15 American League (AL) teams and the 15 National League (NL) teams. Imagine that all AL pitching coaches stress throwing a strike with the first pitch, but all of their NL counterparts have “nibble around the corners” as their mantra: They advocate throwing the first pitch wide of the plate on the assumption that overeager batters will swing at it anyway.

Imagine that young AL pitchers respond in one of two ways to that teaching. Half absorb it, practice it, and stay with it—and they give up fewer runs than NL pitchers. The other half ignore or rebel against the teaching and give up more runs than the NL hurlers. Thus, on average the AL and NL results are virtually the same, and a social scientist concludes that the “make your first pitch a strike” perspective doesn’t work.

But, of course, it does, because AL and NL pitchers are not hermetically sealed off from each other or the world around them. Some NL pitchers read a best-selling book that advocates first-pitch strikes. Others watch how their AL buddies are faring. Others get tired of falling behind in the count by nibbling at those corners rather than being a confident, purpose-driven pitcher. Everyone finds a different path—via genes? environment? x factors?—to success or failure.

Recommended

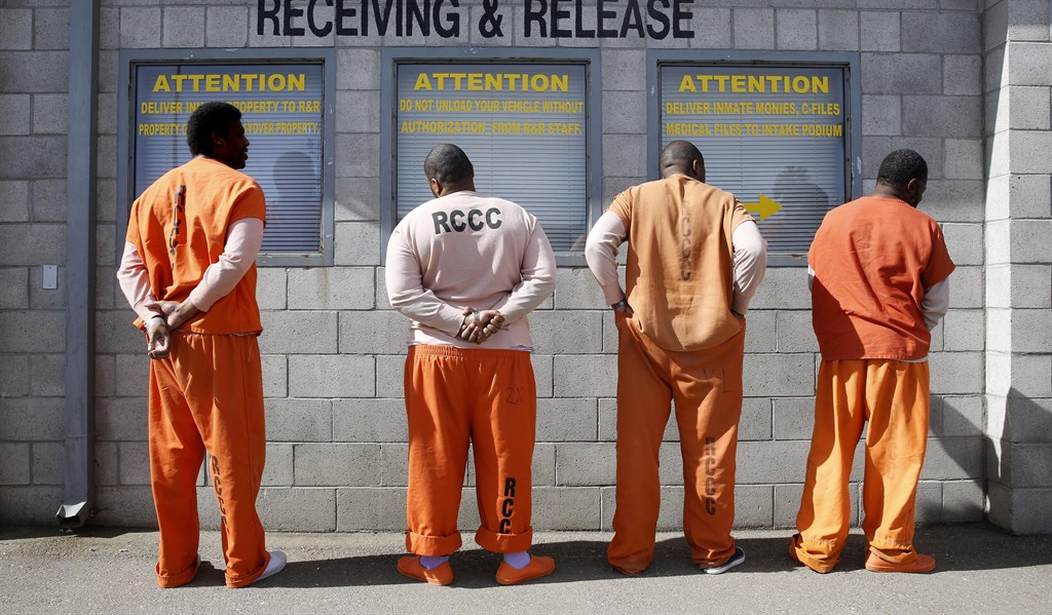

Via a “Washington Post” blog on Feb. 11, 12, and 13, Emory professor Alexander Volokh thrice attacked faith-based prison programs. Volokh was summarizing his “Alabama Law Review” article from late last year, “Do Faith-Based Prisons Work?” He was kind enough to give readers the executive summary—“Short answer: no”—even though some lengthy studies have given a longer answer: yes.

For example, a Michigan faith-based prison program had a recidivism (rearrest) rate of 18 percent for graduates compared to 57 percent of inmates with similar backgrounds and offenses who were not part of the program. In Texas, most ex-cons also get rearrested, but a Christian program showed a rearrest rate of 17 percent and a reincarceration rate of 8 percent among those who stuck with the program. And so on.

Sticking with the program is Volokh’s sticking point. He contends that the only legitimate comparison to secular programs, or no program at all, comes when the faith-based program counts everyone who enters it, even if he drops out after an hour. If a program admits 100 inmates and the 50 who graduate are not rearrested, but the 50 who drop out are, the program’s success rate is only 50 percent: Volokh says “we shouldn’t divide the sample based on participation level, since this introduces a new source of self-selection bias.”

I’m commenting further regarding the bias issue on wng.org, but here’s what’s crucial: A faith-based program—OK, let’s cut the euphemisms and say (90 percent of the time) “Christian program”—is more like communion than magic. It’s not pixie dust. Rather, it intensifies the life or death, God or Satan decision we all have to make at some point during our lives.

Prisoners who enter a Christian program often want to because they’ve had failure after failure: They are not more likely to succeed than others, just more desperate. Christian programs lead prisoners to water, but only God can make them drink. Those who turn aside miss their great opportunity, and may even increase their commitment to evil. That’s why it’s important to compare program graduates with the general prison population. By doing so we see that faith-based prisons (and other faith-based programs) do work for some but not all—and that’s a surprise only to those who believe in magic.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member