Y.A. Tittle died last week. A Hall of Fame quarterback for the New York Giants, he is best known for the taking a knee on a football field. Actually, it was two knees.

In September 1964, the Giants were facing the Pittsburgh Steelers at old Pitt Stadium. Tittle was 38 years old and at the tail end of a 17-year professional career. He had led his team to three straight NFL Championship Games, in ’61, ’62, and ’63, but did not win.

In the game against the Steelers, he dropped back into his own end zone to throw a pass. He was viciously knocked to the ground and his helmet flew off. The pass was intercepted for a touchdown.

He struggled to his knees and stared blankly into the open field, bleeding from his head. The other players backed off and left him to himself. At that moment, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette photographer Morris Berman snapped a picture.

It is among the greatest sports photographs ever taken. There is Muhammad Ali standing over Sonny Liston and Ben Hogan with his one iron at Merion’s final hole. But those are about achievement and victory. This is about the struggle to rise after being knocked down.

People watch the NFL to revel in such mythology. A game where redemption is purchased at a great physical cost serves as an allegory for the common man.

In the 1960s, American culture was fracturing along a fault line, with the common man on one side and scorn against his mores and values on the other. The league’s commissioner at the time, Pete Rozelle, chose to take the side of ordinary Americans in the raging culture war, because they were his natural audience. The league sent star players to visit troops in Vietnam and issued rules requiring players to stand upright during the playing of the National Anthem.

Recommended

In 1967, the NFL produced a film that combined sideline and game footage titled, “They Call It Pro Football.” The film was unapologetically hokey. It was crew cuts and high tops and lots of chain smoking into sideline telephones. With a non-rock, non-folk, non-“what’s happening now” soundtrack, heavy on trumpets and kettle drums. John Facenda, who would come to be called “The Voice of God” for his work with NFL Films, provided the vaulting narration. The production began with the words, “It starts with a whistle and ends with a gun.” There was nothing Radical Chic about it.

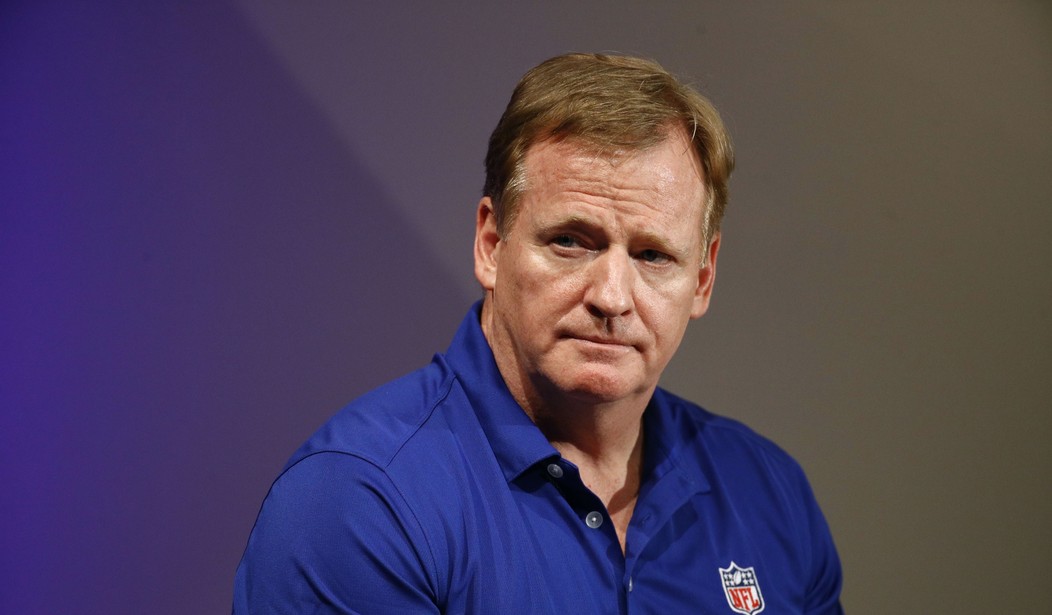

The NFL surpassed baseball as America’s pastime with careful branding that conformed to the tastes and sensibilities of middle-class Americans – Nixon’s silent majority. A half century later, Roger Goodell would kill the goose that laid the golden egg.

In August 2016, America was experiencing a polarizing presidential election. San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick sat during the playing of the national anthem, to protest injustice. It was a politically divisive act directed at fans who regard the national anthem as something sacred. The league did not lift a finger to stop him.

Most employers don’t let their workers make controversial political statements to their customers. It is why you do not know your UPS driver’s views on the expansion of NATO. The Constitution does not prohibit private businesses from regulating speech during work.

A savvier commissioner would have reminded Kaepernick that he is being paid millions to wear the logo of the NFL, and the league does not permit players to use its brand to flaunt their personal politics. Instead, Roger Goodell permitted the pregame ceremonies to become the focus of intense political scrutiny, as the media lined up to catalog whether players stood, sat or knelt during the national anthem.

He knew, no doubt, that protesting the national anthem would be offensive to some people. With Hillary Clinton’s inevitable triumph looming, it was generally considered okay to offend those people. They would be described by Hillary Clinton a few days after Kaepernick’s protest as a basket of deplorables. The NFL was just pandering to the prevailing sentiment when it green lighted Kaepernick’s cause. Then Trump won.

The rule before Trump was that half the country had to endure any scold, put up with all name calling, and generally be treated like idiots by popular culture. The brilliant lights who made the rules never considered that scolding half the country may, in itself, have been divisive. And that people have been stewing about it for years.

When the 2017 seasons started, President Trump railed at the NFL for permitting the protests. Rather than back down, the NFL doubled down, employing the double speak of the cornered weakling. Try to imagine John Facenda speaking the words, “The NFL and our players are at our best when we help create a sense of unity in our country and our culture” – you can’t.

Television ratings have tanked. By permitting its games to become a forum for liberal politics, the NFL broke faith with its fan base.

Y.A. Tittle quit football after kneeling in the end zone and sold insurance. He hung Berman’s photograph in his office with the caption, “Nothing Comes Easy.” Last week, his death coincided with the end the NFL mythology he represented. The league is no longer a fanfare for the common man, an allegory about the struggle to get up after being knocked down.

It is easy to drop to one knee in a deliberate pose to protest something. Rising from two knees after spending yourself in a physical battle, that’s not so easy. It is why people watched, Roger.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member