To that nagging question, the answer increasingly seems to be yes.

Certainly, they were a novelty. As novelist Lionel Shriver writes, "We've never before responded to a contagion by closing down whole countries." As I noted in May, the 1957-58 Asian flu killed between 70,000 and 116,000 Americans, between 0.04% and 0.07% of the nation's population. The 1968-70 Hong Kong flu killed about 100,000, 0.05% of the population.

The U.S. coronavirus death toll of 186,000 is 0.055% of the current population. It will go higher, but it's about the same magnitude as those two flus, and it has been less deadly to those under 65 than the flus were. Yet there were no statewide lockdowns; no massive school closings; no closings of office buildings and factories, restaurants and museums. No one considered shutting down Woodstock.

Why are attitudes so different today? Perhaps we have greater confidence in government's effectiveness. If public policy can affect climate change, it can stamp out a virus.

Plus, we're much more risk-averse. Children aren't allowed to walk to school; jungle gyms have vanished from playgrounds; and college students are shielded from microaggressions. We have a "safetyism mindset," as Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff write in "The Coddling of the American Mind," under which "many aspects of students' lives needed to be carefully regulated by adults, and that it was far better to overreact to potential risks and threats than to underreact."

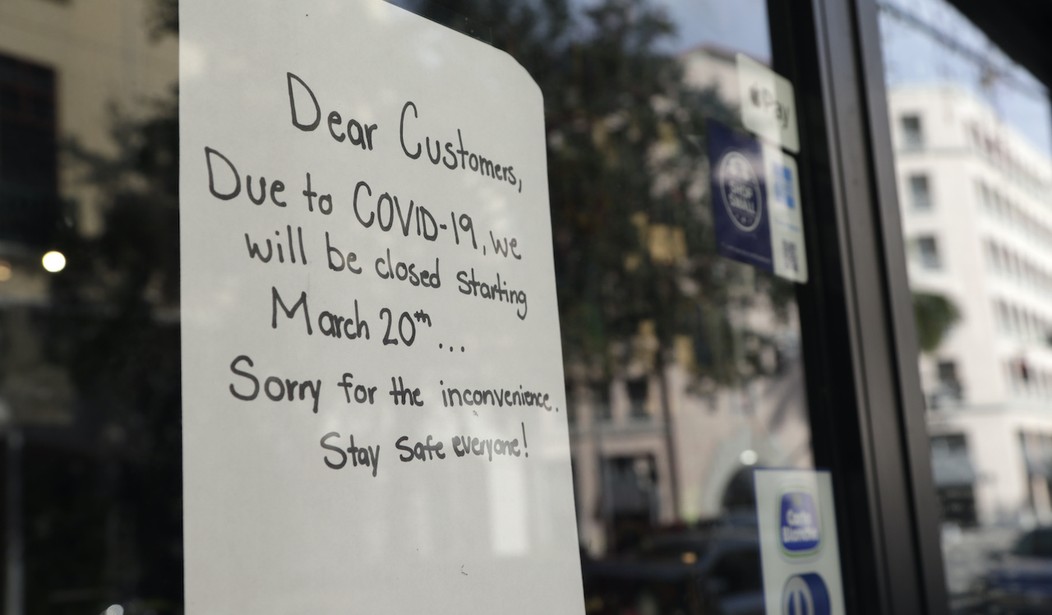

So the news of the COVID-19 virus killing dozens and overloading hospitals in Bergamo, Italy, triggered a flight to safety and restriction. Many Americans stopped going to restaurants and shops even before the lockdowns were ordered in March and April. The exaggerated projections of some epidemiologists, with a professional interest in forecasting pandemics, triggered demands that governments act.

Recommended

The legitimate fears that hospitals would be overwhelmed apparently explain the (in retrospect, deadly) orders of the governors of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Michigan requiring elderly care facilities to admit COVID-infected patients. And the original purpose to "flatten the curve" segued into "stamp out the virus."

But the apparent success of South Korea and island nations -- Taiwan, Singapore, New Zealand -- in doing so could never be replicated in the continental, globalized United States.

Governors imposing continued lockdowns claimed to be "following the science." But only in one dimension: reducing the immediate number of COVID-19 cases. The lockdowns also prevented cancer screenings, heart attack treatment and substance abuse counseling, the absence of which resulted in a large but hard-to-estimate number of deaths. What Haidt and Lukianoff call "vindictive protectiveness" turned out to be not very protective.

Examples include shaming beachgoers though outdoor virus spread is minimal; extending school closedowns though few children get or transmit the infection; closing down gardening aisles in superstores; and barring church services while blessing inevitably noisy and crowded demonstrations for politically favored causes.

The new thinking on lockdowns, as Greg Ip reported in The Wall Street Journal last week, is that "they're overly blunt and costly." That supports President Donald Trump's mid-April statement that, "A prolonged lockdown combined with a forced economic depression would inflict an immense and wide-ranging toll on public health."

For many, that economic damage has been of Great Depression proportions. Restaurants and small businesses have been closed forever, even before the last three months of "mostly peaceful" urban rioting. Losses have been concentrated on those with low income and little wealth, while the lockdowns have added tens of billions to the net worth of Amazon's Jeff Bezos and Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg.

Attitudes on lockdowns are highly correlated with partisan politics. Democrats tend to be more risk-averse and want lockdowns continued until there's a vaccine. Republicans are less risk-averse and want most restrictions lifted.

As a result, since governors and mayors make these decisions, it's heavily Democratic central cities -- New York, Washington, Los Angeles, San Francisco -- whose civic fabric is being rent and cultural capital is left in ruins, with much less devastation in the exurbs and countryside.

This fouling your own nest extends to voting. Many more Democrats than Republicans want to vote by mail, even though the risk of voter error or non-counting is higher than for those, most of them Republicans, who want to vote in person.

The anti-lockdown blogger (and former New York Times reporter) Alex Berenson makes a powerful case that lockdowns delayed, rather than prevented, infections, and that current plunging hospitalization and death rates suggest we're approaching herd immunity, where the virus will fade out for lack of new targets.

There are old lessons here, ready to be relearned. Governments can sometimes channel but never entirely control nature. There is no way to entirely eliminate risk. Attempts to reduce one risk may increase others. Amid uncertainty, people make mistakes. Like, maybe, the lockdowns.

Michael Barone is a senior political analyst for the Washington Examiner, resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and longtime co-author of The Almanac of American Politics.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member