The nation is just past halftime in the 2018 primary election cycle. Twenty states -- containing the majority, 228 of 435, of House districts -- have held their primaries, and all but the three with runoffs have chosen their nominees.

The latest results, taken together with the generic vote -- polls asking which party's House candidate you'll vote for -- undercut the many gleeful predictions of a blue wave that will produce a big Democratic majority in the House and perhaps the Senate, as well.

The RealClearPolitics average of recent polls shows the Democrats' lead over Republicans on the generic vote declining from a 13-point margin (49 to 36 percent) last December to a 3-point margin (43 to 40 percent) going into Tuesday's primaries. Given Democrats' disadvantage of having so many of their voters clustered in heavily Democratic seats, that suggests a statistical tie. That would mirror the CBS News estimate of 219 seats for Democrats and 216 for Republicans, with a plus or minus nine-seat margin of error. Donald Trump's 44 percent job approval rating, well above his 38 percent favorable rating in November 2016, points in the same direction.

Tuesday's results tend to confirm this. Most closely watched was California, with its 53 House seats. The main focus there was on the seven seats held by Republicans but carried by Hillary Clinton in 2016. These obvious Democratic targets represent almost one-third of the net gain Democrats need for a House majority.

Recommended

Both parties got some good news from these seven districts' results.

Democrats feared that the combination of California's having a "jungle primary," in which the top two candidates regardless of party go on to the general election, and the large number of enthusiastic anti-Trump Democrats running would produce "lockouts" -- i.e., general elections with two Republicans.

That didn't happen. Nor do Democrats seem to have nominated many flaky candidates as parties sometimes do when flocks of enthusiastic newcomers run.

The good news for Republicans is that these districts look less Democratic than they did in November 2016. Clinton outpolled Trump in all seven then, but this time Republicans got combined majorities of between 53 percent and 63 percent in six of the seven. And in the seventh, the total Democratic lead was just 51 to 48 percent.

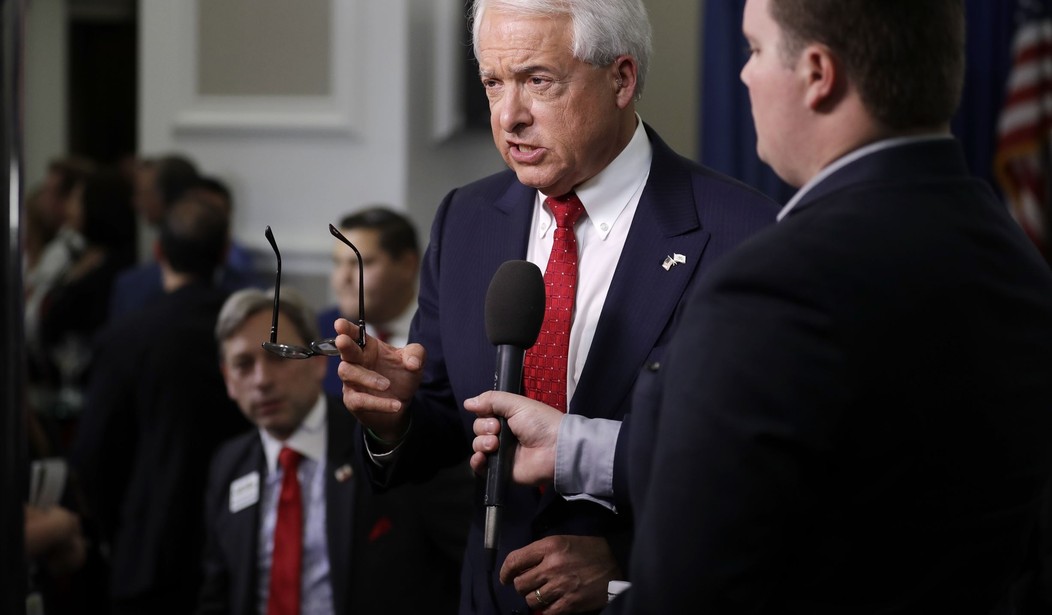

More good news for Republicans. They won't suffer from a lockout in the top statewide race as they did in 2016; they'll have a gubernatorial candidate, John Cox, this November. And though there's time for opinion to shift, past jungle primary results in California, Washington and Louisiana have often been good indicators of the vote in November.

Issues can make a difference, too. Voters in the intersection of Orange, Los Angeles and San Bernardino counties overwhelming (by an 18-point margin) recalled a Democratic state senator who had voted for a gas tax increase, and they installed a Republican in his place. In the overlapping 39th Congressional District, vacated by veteran Republican Ed Royce and considered a prime target by Democrats, Republicans outpolled Democrats by a 10-point margin.

Writing before Tuesday on the left-wing blog Daily Kos, Daniel Donner argued that in 2017-18 state and special elections, "Democratic overperformance is concentrated in red states and districts that shifted red in 2016" -- places where whites without a college degree gave Trump higher percentages than more conventional Republicans.

In other words, those results look more like the divisions that have prevailed in all but two off-year cycles starting in 1994. Similarly, California's seven Clinton/Republican districts -- which swung away from Trump in 2016, with their high percentages of college-educated whites and/or Hispanics -- seem to have swung some distance back to the 1994-2014 norm this year.

This would be in line with polling that shows Trump enjoying almost universal job approval among self-identified Republicans -- higher than all but one post-World War II president enjoyed at this stage in their tenures from their fellow party members.

The 1994-2014 partisan divisions have been unusually long-enduring, aside from the short-lived shift to Democrats in 2006-08, and the actual number of Obama/Trump voters who switched 100 electoral votes to the Republican was small by historical standards.

Will a reversion to that norm give Republicans a narrow House majority once again this year? That's one result -- though certainly not the only result -- consistent with the primary results we've seen so far. Opinion can shift; perhaps another blue wave is building. But the one almost everyone was expecting six months ago seems to have crested and ebbed.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member