Last week, Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee Chairman Gary Peters (D-Mich.) announced the launch of an investigation into the recent string of ransomware attacks against U.S. firms and infrastructure. That followed a formal, multi-ally announcement the day before accusing Chinese intelligence of directing an attack against Microsoft Exchange servers used by American businesses, non-profits, and academic institutions.

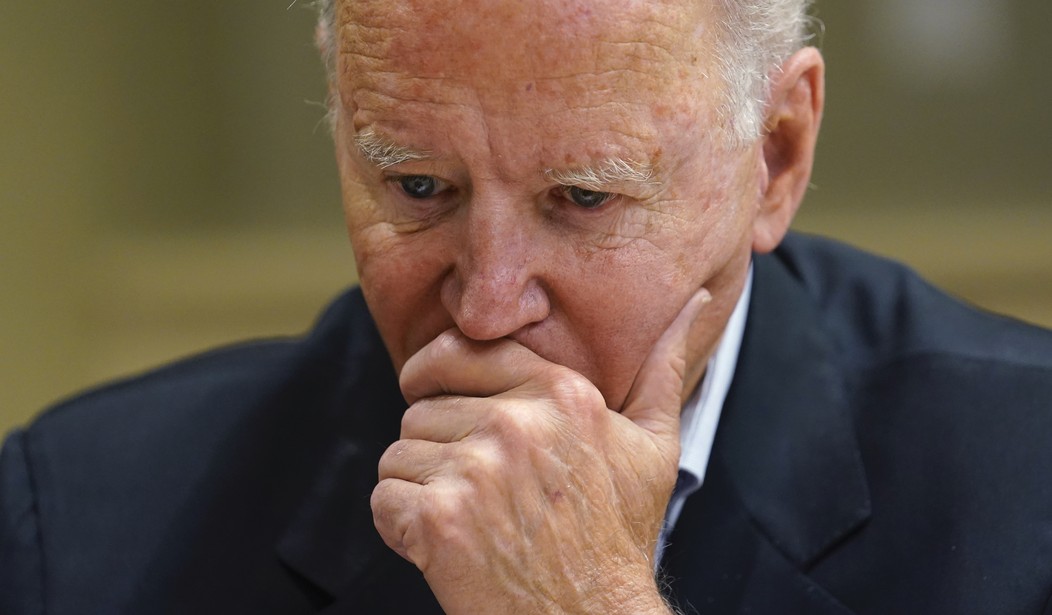

These announcements came on the heels of a series of inward-facing steps outlined by the Biden administration between early June and mid-July, representing the early turning of gears as Washington reluctantly pivots towards ransomware and other major cyberattacks. We saw the standup of a ransomware task force at DOJ, instructions for businesses on cyber-resiliency, and the expansion of focus of an existing State Department rewards program to include cyberattacks. Just yesterday the administration announced that some of these mandates for business will become mandatory for companies operating in federally defined critical sectors.

All this activity – the new initiatives and the formal announcements – all of it, is wrongheaded and its unhelpful. We are overdue for an adjustment. We need to right now begin to have a serious conversation centered around another perspective, one that rejects this type of disruption and subversion as a fait accompli. If we do so, and broaden the discussion now, we might discover what a model of credible, effective cyber-deterrence could look like.

In 1993, President Clinton ordered airstrikes against an intelligence complex in downtown Baghdad as both a retaliation and a warning after details emerged that Iraqi agents had attempted an assassination of former President Bush. The strikes took place around 1-2am, timed to minimize civilian casualties, and the physical damage was widely considered secondary to the message being sent to the regime and to the world.

Recommended

Airstrikes by previous and successor presidents fit a similar pattern, with usually similar precautions taken and – rightly or wrongly – words like surgical, smart, or more recently targeted, accompanying the word airstrike. From Reagan in Libya, Clinton also in Sudan and Afghanistan, to Obama and Trump in Syria, these limited-in-scope military actions are a comfortably accepted tool of presidential foreign policy.

It is time to take that precedent, looking to those reasonably successful uses of limited force, and discuss what they will look like in the cyber-realm. The United States needs to now seriously consider Retaliatory Cyber-Responses (RCRs) distinct from our traditional and ongoing cyber espionage activities.

The risks of such a course are apparent, and it’s natural for us to immediately jump to the risk of inviting further escalation from our adversaries in an area of such recently demonstrated domestic vulnerability. But what’s missing from that analysis is that we are already living those risks. And in the majority of the aforementioned responsive or deterrent strikes conducted by previous U.S. presidents, the tradeoff between retaliation and deterrence has normally weighed in our favor.

We now live in the era of the risks we fear unleashing, our mindset just needs to catch up. Our adversaries, state and nonstate, have made that choice for us, and are in an era of infrastructure-threatening cyber-subversion. A credible deterrent requires us to abandon the failed law enforcement model, but also on going beyond shadowy Cyber Command activity, and embracing higher risk and better returns. We must consider retaliatory and public cyber responses: if a pipeline in the U.S. goes down, a pipeline in the country the attack originated from should experience a disruption of some kind in that same sector. Again, in the model of targeted airstrikes we can and should minimize the type and length of the disruption and guard against unintended cyber-collateral damage. But the effects our of response should be recognizable to the foreign leader – and potentially both that country’s public and the American public – as the deliberate and intended result of American retaliation.

American unwillingness to respond sufficiently to what were precedent-setting acts of cyber-subversion is creating greater long-tail risk than a heartier response, and at the same time allows our adversaries to set the terms of escalation. We remain bound by a ruleset that isn’t working, doesn’t prevent disruption to the homeland, and ensures the pain and risk are felt only on one side. They shut down a pipeline, we shut down a website.

Innovation in RCRs is risky. U.S. Critical Infrastructure Sectors – the list of sixteen sectors Biden warned Putin were off limits – were designated as such nearly a decade ago in an updated presidential directive as areas deserving of additional security and resiliency measures. That’s because attacks against those sectors are judged to immediately impede U.S. safety or put U.S. lives in danger, in addition to a few other significant risks. That’s why, for example, the Emergency Response Sector and the Water Supply/Wastewater Sector appear on the list. This is not an argument that we should target critical infrastructure, it’s instead mentioned to highlight that the consequences and the risks to cyber-retaliation are immediate and very much non-virtual, just like action in these areas always is. One can think of the Al-Shifa pharmaceutical plant airstrike in 1998 as an example of when this kind of attack yields much blowback and little benefit. However, by setting a definitive and roundly noticed deterrent, we brook less overall risk and the benefits of time-boxing it than if we allow the cycle of provocation to continue unreturned and of unknown length.

Embracing RCR may put a chill on relations with countries this administration is hoping to get to join big ticket climate efforts and other actions, but if the only way to get them on board is to respond fecklessly to aggression, then our ability to lead isn’t sustainable regardless. Put the ransomware criminals and the hackers – and the nations that harbor and sponsor them – back in the box, and we can more effectively shrink the cyberattack ‘file’ in our foreign relations. By shortening the timeframe of conflict and shrinking the collective foreign affairs attention it commands, we will actually be better positioned to move forward on other issues, and we’ll be doing so on firmer and better respected footing.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member