Earlier this year during the first week in March we visited Disney in Orlando, Florida. We live in West Palm Beach so it was a mere two-and-a-half hour drive north on Florida’s Turnpike to the parks and our hotel.

It was during spring break and the first half of the week was spent entertaining guests from New Jersey who wanted to enjoy the warm weather and attend a couple of spring training games and watch the Astros play the Nationals at Fitteam Ballpark. That left us with only four days to visit two parks so we decided we’d go to Disney Studios to check out the new Star Wars attraction and then spend a second day at Epcot.

I had been to Disney many times before but had never seen the parks so crowded. People from all over the world had come to Florida! We waited 90 minutes in one line for a brief 5-minute ride on Han Solo’s Millennium Falcon.

The main attraction, Galaxy’s Edge, had such a long waiting list we were placed on “standby” (and when the ride broke down late in the afternoon, we were forced to give up).

The next day dawned a chilly March morning in the 50s. Epcot turned out to be just as packed as Disney Studios. It was almost impossible to get a seat in a restaurant without having to wait at least a half hour.

We returned to West Palm late Saturday afternoon wondering if we’d have another opportunity in the near future to use the third day of our 3-day park passes.

On Sunday I woke up feeling a bit “off.” By that evening my stomach was upset and I was beginning to feel a wave of fatigue. This continued until Wednesday when I began to spike a low fever of 99.6. My appetite disappeared and I spent most of the next two days struggling to get through my classes despite having slept 10 hours on each of the previous two nights.

Recommended

I felt better over the weekend but the following week the fever and malaise returned. And Disney had closed all of its parks due to the COVID-19 pandemic, something that was hardly comforting.

By the end of the second week I had fully recovered from whatever it was I had caught without ever developing a cough or losing my sense of taste and smell. But I wondered: Did I have a mild case of COVID-19?

In March it was nearly impossible to be tested for COVID-19 and even less likely to get an antibody test. By May that had changed.

As pleas for convalescent plasma donations from people previously infected mounted, I was finally able to get tested for IgG and IgM COVID-19 antibodies in the hopes of donating blood to perhaps save someone’s life.

To my disappointment my test came back negative. This was one of the first tests available and it wasn’t an FDA authorized test. Perhaps my results were a false negative, I thought.

Five weeks later I was tested again, this time by a different, FDA authorized test. Again, the results came back negative.

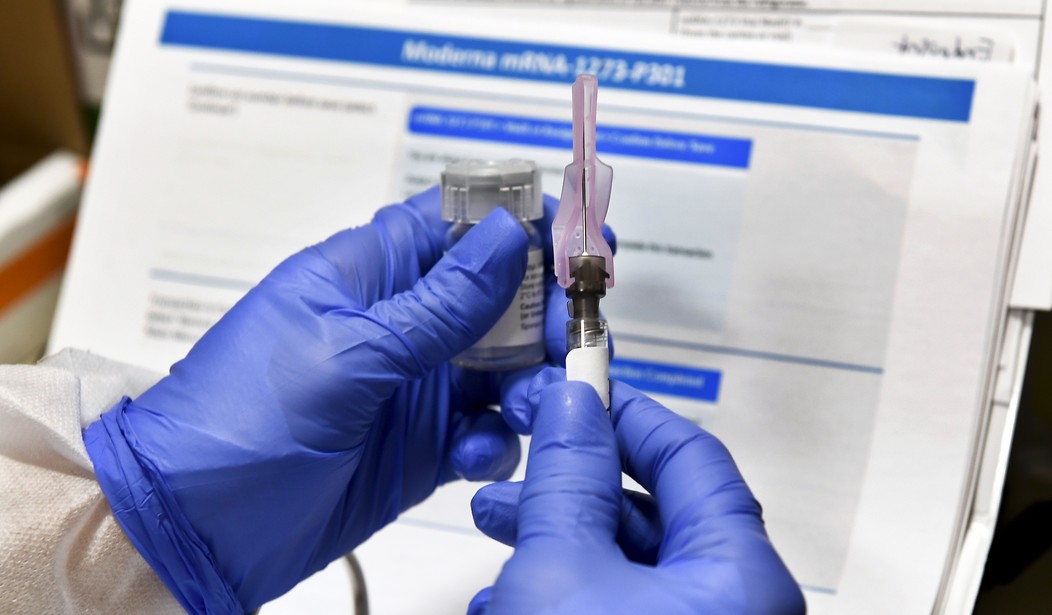

Frustrated at not being able to do anything to help those who were sick and dying, I learned that Moderna Inc. was planning phase 3 clinical studies of its mRNA 1273 vaccine in various cities across the U.S. Three studies would take place in south Florida, one of them at the Palm Beach Research Center, a mere five-minute drive from my university office.

After some digging around on the Internet, a Facebook post of mine that got the attention of a journalism student which led to a short interview on WLRN Radio Miami, South Florida, I learned where and how to volunteer.

I became Patient 001 out of the 1,000 the center was looking to sign up for Moderna’s 2-year phase 3 clinical study of its mRNA-1273 vaccine.

Some of my friends thought I was crazy. “That vaccine will re-write your genetic code,” one warned on a Facebook post. “You’re going to become a 5G cellphone tower,” another commented. “I hope you don’t grow a second head or a third eye,” a nurse friend of mine joked.

But I had done my homework. I wasn’t about to go into this blindly. I had read about the results of the early stage phase one clinical study where in “two weeks after the second dose (day 43), participants receiving the 25 microgram dose of mRNA-1273 had levels of antibodies that bind to the novel coronavirus at similar levels to those seen in patients who have recovered from COVID-19.”

While there were reactions to the vaccine – nothing unexpected – they were mild such as malaise, soreness at the injection site and fevers. No one had experienced a cytokine storm, a potentially deadly immune reaction caused by the body’s own defenses to the virus.

I reported to the center on July 31 for my first visit, a two-hour preliminary screening which included a thorough medical history and a physical exam. During the course of the two hours various health care professionals came into my room and introduced themselves: nurses, doctors, PAs, pharmacists and phlebotomists, all of them gushing with gratitude because I had volunteered for this study. They went out of their way to express this on several occasions. “We need to get our lives back,” one of the doctors commented. “Thank you so much for your willingness to be a part of this study.”

I returned the following Monday, for the second two-hour appointment which included another short interview, a COVID-19 nasal swab, a visit to a phlebotomist who cheerfully stuck me with a needle and withdrew eight vials of blood from a vein and, finally, the two pharmacists who administered the first injection into the deltoid muscle of my left arm.

Then I laid down for 30 minutes on a comfortable bed in an examination room to be observed for any adverse reactions. There were none.

Follow-up over the next seven days consisted of daily responses to a series of questions on an e-diary that I had downloaded and installed on my iPhone. The questions addressed possible side effects and I had to take my temperature every morning as well as report on any fatigue, nausea or headaches I experienced.

The only symptoms I experienced after the first injection were a mild headache and slight fatigue the first day in the evening followed by very mild muscle aches the next morning.

I returned to the center on August 28 for my third visit. Again, I was swabbed for COVID-19, donated another eight vials of blood and received my second injection.

The study is a “double blind.” No one, including the doctors and the pharmacists, are supposed to know whether a patient is receiving the actual mRNA vaccine or sterile saline. But the doctor who is running the study commented to me. “I can’t believe they would give Patient 001 a placebo.”

His intuition may have been correct.

Four hours later I spiked a small fever – around the same temperature as I had experienced in March after we had been to Disney for three days. I also experienced mild body aches – nothing that interfered with activity – but I felt like I needed to lay down and go to bed early.

The next morning, I woke up with mild body aches but I went out and rode 15 miles on my bicycle anyway. Later that evening a low-grade fever returned. By the third day, any side effects to the vaccine were over.

There are several reasons why I am participating in this study. As a citizen I believe this is my civic responsibility. I am old enough to have actually heard President John F. Kennedy utter these famous words in his 1961 inaugural address: “Ask not what your country can do for you. Ask what you can do for your country,” a message largely lost on a generation of young people today. I refuse to sit idly by and watch as people my age and older live in fear because of the very real risk of becoming ill and dying just because they went to work or to eat out at a restaurant or go to a family gathering. We know of several families who went through hell on earth as loved ones died alone in hospital intensive care wards.

I am participating in this study because as a scientist, this is history in the making. Although there have been coronavirus vaccines administered to animals for decades, there has never been an mRNA virus successfully developed and approved by the FDA for injection into humans.

And lastly, my faith constrains me to do this. Bible verses such as “[W]e who are strong ought to bear the weaknesses of those without strength,” and “From everyone who has been given much, much will be required,” are challenges to live out of my comfort zone to exercise faith, not just talk about it. I dare not compare my efforts to the real heroes – the healthcare professionals who have risked their lives on the front lines by running into the middle of this pandemic to save the lives of others. But my involvement, as small as it is, is something.

As one piece of a 30,000-piece jigsaw puzzle, if my involvement facilitates the final approval of a safe and effective vaccine for COVID-19, we will get our lives back again.

Gregory J. Rummo is a Lecturer of Chemistry at Palm Beach Atlantic University and a Contributing Writer for The Cornwall Alliance for the Stewardship of Creation. The views expressed in his columns are his own.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member