Editor's Note: This column was co-written by Dr. Kent D. MacDonald and Dr. Timothy G. Nash

***

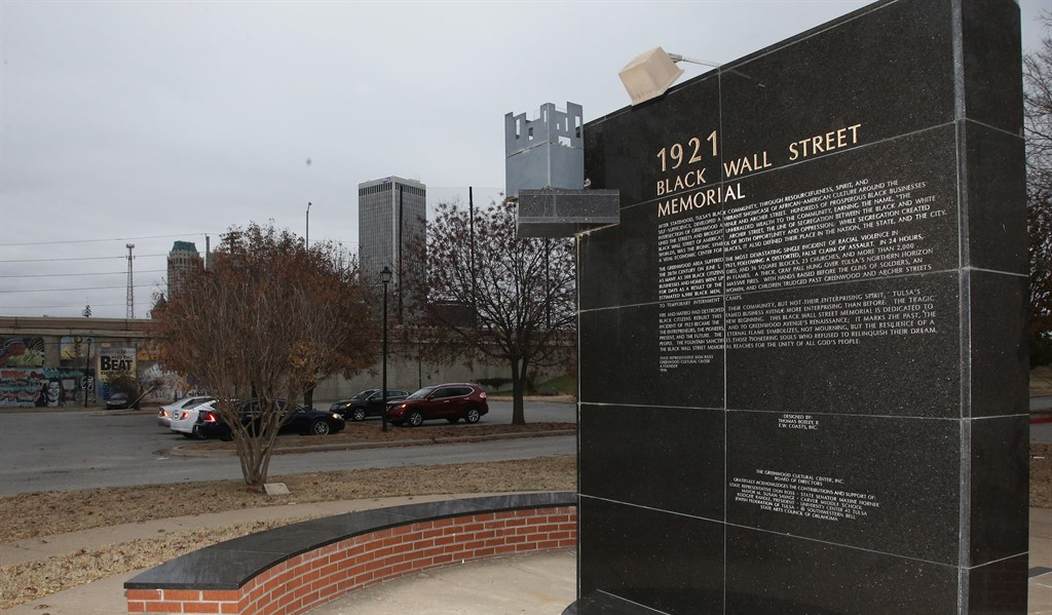

Just over 100 years ago, the Greenwood District – a 40-square-block area of Tulsa, Oklahoma – was the thriving epitome of American economic and entrepreneurial activity, leveraging the success of Oklahoma’s oil boom. What made the Greenwood District different is that it was home to Black-owned restaurants, hotels, insurance companies, professional offices, dance halls, grocery stores, and movie theaters.

One of America’s wealthiest African American communities, the Greenwood District was hailed as the “Black Wall Street of America” – a shining example of the life-changing impact potential of American free enterprise. Most remarkably, the Greenwood District’s success came less than 60 years after emancipation. Black Wall Street emerged as a model for other African American communities to proactively achieve economic and social prosperity.

Tragically, this beacon of prosperity was violently destroyed in just 24 hours, between May 31 and June 1, 1921, by mobs of white Tulsans jealous of their Black neighbors’ success (some had even been deputized and provided weapons). Over those two days, Greenwood businesses and homes were burned to the ground, thousands were injured, and hundreds were murdered in a massacre that is still considered to be one of America’s worst single acts of racial violence in U.S. history.

Beyond the unspeakable carnage, perhaps equally tragic is that these events, now known as the Tulsa Race Riots of 1921, would be largely forgotten for almost 100 years.

To better understand this evil perpetrated by citizens against citizens, we must look beyond those two repugnant days in 1921 and remind ourselves that Oklahoma had been considered a haven for Black people since the Civil War. Dozens of Black townships and settlements were established in Oklahoma, with the Greenwood District serving as the most prosperous community – proudly “built for Black people, by Black people.”

Recommended

While these communities were growing and prospering, racism and resentment had been lingering among white Tulsans for years. It would take little to spark a riot, and that flashpoint began when 19-year-old Dick Rowland, a young Black American with a shoe-shine business, was accused of assaulting a white elevator operator named Sarah Page. When the Tulsa Tribune shared news of the alleged assault and provided an accompanying editorial demanding a lynching that night, a horrible race riot and massacre soon followed.

As Rowland awaited his right to due process in a local jail, throngs of Blacks and whites gathered at the courthouse. When the Blacks made it clear they would protect Rowland’s right to a speedy and fair trial, the unruly white mob ignited the riot that would destroy Greenwood.

The once-thriving Greenwood District had more than 1,400 homes and businesses burned to the ground, and nearly 10,000 people were left homeless. While “the official” Greenwood death toll was recorded at 10 whites and 26 Blacks, many experts today believe at least 300 people were killed (mostly Blacks).

As America celebrates Black History Month, it is time to intensify the light on one of the worst stains on American history. Although there have been attempts to return Greenwood to its former stature after the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, the community never could recapture the success and prosperity it once enjoyed.

The destruction of Black Wall Street led to severe economic and social losses for the people of Tulsa. Especially important to note is that the inter-generational wealth acquired by black citizens would never be passed on to family members. Many of the thousands of victims who were displaced during those terrible days, never returned. Many survivors and their families never recovered socially or economically.

Hopeful signs in America since the Tulsa Riots

Since this calamity, America has experienced many positive changes within the Black community. The number of Black members of Congress has increased. A Black president presided for two historical terms. Soon, we will likely have two Blacks seated on the nine-member United States Supreme Court. Further, a record number of Blacks now hold federal judgeships. And our current Vice President is Black. The color barrier has been broken in all professional sports in the United States, with Black athletes playing a significant role in baseball and literally dominating in football and basketball. Since 1921, Black Americans have won numerous Academy Awards, traveled in space, and won Nobel Prizes.

Economically, there also are reasons to celebrate within the Black community. The Multicultural Economy Report from the University of Georgia’s Selig Center for Economic Growth estimates minority buying power in the U.S. and all 50 states have increased over the past 30 years. It estimates the buying power for Black, Asian, Hispanic, and Native Americans is up from $671 billion in 1990 to $4.9 trillion today. The total buying power of this demographic increased from 15.6% of the U.S. economy in 1990 to 28.3% in 2020.

The Selig Center also identified other economic improvements, noting that purchasing power among Black Americans rose to $1.6 trillion or 9% of our nation’s total purchasing power – a number equal to the nominal GDP of Canada!

We are also pleased to see free enterprise continues to be embraced by Black Americans. According to an October 2021 media release by the U. S. Census Bureau, Blacks owned just under 135,000 multi-employee businesses employing 1.3 million people with another 2 million Black businesses serving as single-person sole proprietorships or partnerships.

Within higher education, the number of black first-year medical students increased 21% last fall, bringing in a nationwide class of 2,562 future doctors. Black students made up 11.3% of first-year students in 2021, up from 9.5% in 2020, and the Law School Admission Council declared the incoming class of 2021 to be the most diverse law school class in U.S. history.

America is not perfect, but it is reasonable to note we have come to some distance since 1921, including an ever-growing celebration and understanding of — and appreciation for — Black History Month. By shining a bright light on Black history and re-telling the unimaginable horrors of what happened to Black Wall Street, we create the opportunity to look more deeply at important race-related issues facing the country.

These uncomfortable discussions also present opportunities to talk about difficult realities that still exist in America. We must never forget the lessons of Greenwood, where those who looked different were unjustly singled out and punished mightily, many fatally, for daring to dream big. So too, can these lessons be applied to ideology: We are first and foremost Americans. We should never allow partisan talking points to override the need to engage in open, honest, civil, and peaceful discourse to air our opinions, grievances, and positions.

America has come a long way since Greenwood and with God’s help — and kindness, respect, and love for each other — we will accomplish even greater things as we continue to embrace the principles of life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness, free enterprise, and opportunity and equality for all. Future successes will be achieved not because some law says so but because credentials, hard work, and results demand it to be so.

While we rightfully continue to recognize and mourn the tragedy of Greenwood, let’s also be mindful of the progress we have made as a nation of immigrants and redouble our efforts to improve the lives of all Americans.

Lieutenant Colonel (ret.) Allen B. West is currently a Republican candidate for governor of the state of Texas and a former member of the U.S. Congress from Florida. Dr. Kent D. MacDonald is the president of Northwood University. Dr. Timothy G. Nash is the director of the McNair Center at Northwood University.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member