"They came with a search warrant," softly spoke Samuel B. Fisher, a mild-mannered cattle farmer operating a 100-acre farm tucked away in Virginia's heartland. Fisher's bread-and-butter, Golden Valley Farms, carves out the scenic countryside that's a hop, skip, and a jump away from historic Farmville, a postcard-perfect small Southern town with classical Main Street charm.

The father of five had graciously invited us down to his idyllic pasture to rehash the whirlwind of unforeseen events that unfolded over the cruel summer. It was a tumultuous time on the Fisher farm, an upheaval that threatened to upend the man's livelihood.

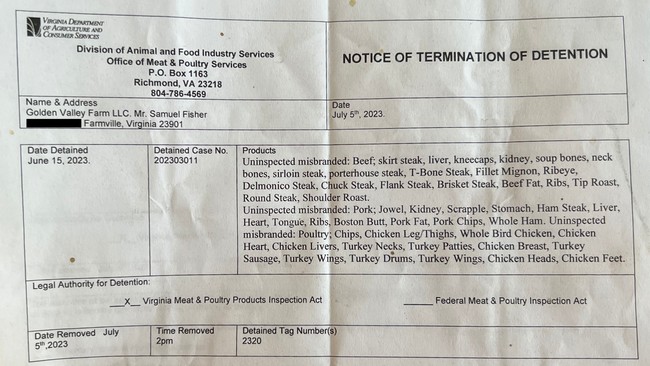

"Then, they tagged the meat, so that we can't touch it; we can't sell it; we can't feed our family with it," Fisher told Townhall.

Fisher's children gathering chicken eggs | Golden Valley Farms website

There, we sat in Fisher's office on the periphery of a multi-purpose barn, surrounded by sparsely scattered cardboard boxes of farm-fresh squash situated across the concrete floor and vintage-style empty half-gallon glass jugs labeled with "Golden Valley Farms CHEMICAL FREE A2/A2 Goat Milk" stickers that lined the nearby shelves, awaiting to be filled and delivered statewide.

Moments earlier, upon our arrival, we were greeted by the welcoming committee: a trio of barefoot, dirt-covered kids holding four-week-old kittens, sized smaller than an ear of corn and clutching the children's arms for dear life. One of the young boys, sporting suspenders and a straw hat with an LED headlamp strapped to it, scurried away to fetch his father—whose workdays begin before daybreak at 5:30 a.m. and end past sundown—from the fields. The other boy, his sandy-haired brother in a bowl haircut, prodded us with a question, asking in a small voice if we'll "put it on the news." Now, the curious children were captivated by the camera, gathered wide-eyed around Fisher after dragging a handful of upside-down milk crates over to perch themselves upon. A little girl, draped in a sunflower-colored dress, bobbed in and out of frame to wrangle one of the family's dogs, as Fisher hushed her in Pennsylvania Dutch. In the neighboring processing-and-packaging room, two girls were hand-sorting chicken heads and feet, a tedious undertaking we would later closely observe prior to embarking on a walking tour of Fisher's picturesque property.

The firestorm of Big Government saber-rattling ignited in mid-June when an inspector with the Virginia Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services (VDACS), without warning, paid the Fisher family a visit. Fisher has "no idea" what could have prompted VDACS's impromptu inspection on June 14, except "maybe they just finally found us through word of mouth," he speculated.

What was clear: The state sought to penalize Fisher for selling meat that was not processed by a USDA-inspected facility (U.S. Department of Agriculture). Fisher processes—an industry euphemism for butchering—his farm-raised meat on-site and sells it directly to his customers, feeding about 500 consumers and their families, who are part of a buying club. As members enrolled in the Golden Valley Farms membership program, they've bought into Fisher's herd of 100% grass-fed golden Guernsey cows.

Recommended

"They own part of the business. They own some of the herd," Fisher explained. "My thinking was [...] We can butcher their cows, process it, and sell it to them. I told the state all of this, but they said, 'No, there's no way around that. You can't do that.' They asked permission to get in here" to search the farm, a request Fisher denied. "And, they told me, 'We'll be back,' and left."

The next day, on June 15, the VDACS inspector did, indeed, return—this time with a Cumberland County sheriff's deputy to serve Fisher a search warrant. "They went through everything, house, every building, in the barn. They just raided through everything, put their nose in everything, and wanted to know every detail of everything. They went out back, trying to find all the failure they can find on a farm, which, of course, some of their stuff, which they think is wrong, is just normal stuff on a farm," Fisher stated.

"I wasn't on the farm at the time" of the full-scale raid that lasted approximately three to four hours, Fisher added.

Then, the state slapped a tag on Fisher's walk-in freezer, placing the meat under "administrative detention" and declaring that he wasn't supposed to take any meat out of his own storage room. By the weekend, his kids were crying for scrapple, a mush of pork scraps and trimmings characteristic of Amish country, that sat behind the door on Fisher's property that should, otherwise, be open and easily accessible. The following Monday, Fisher "even made a special phone call," asking again, "if that's the way it is." And, as Fisher recounted, the VDACS inspector replied, "Yes, cannot feed your family with it, cannot do anything with it."

Detention notice | Virginia Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services record

There's "nothing illegal" about Fisher processing his own meat and eating it for his own consumption, asserted Mindy, the farm's officer manager, who oversees sales, handles email marketing, and fulfills online orders. "So, he decided he was gonna go and feed his family, and since he would most likely be fined for doing that, he decided to open up meat sales again. Because if he's going to be fined, he's going to be fined, and you might as well do it," she, wanting to go by "just Mindy," stated matter-of-factly.

"Anybody can go and raise animals for their own family to eat. That's where I got to the point: He [the VDACS inspector] crossed the line, so I'm going to cross the line," continued Fisher, declaring, "He crossed the line by telling me I cannot feed my own family with this meat. So, I decided I'm going to cross the line. I'm going to sell it. And that's why I didn't honor the state."

"This ain't right," an incensed Fisher further expressed. "We're going to feed our family. We're going to feed our customers [...] So, we did not honor that tag. We sold the meat, some meat, out of there [the tagged freezer], whatever customers ordered. Then, the state came back and saw what we did. They really gave me a mouthful for doing that," the farmer recalled.

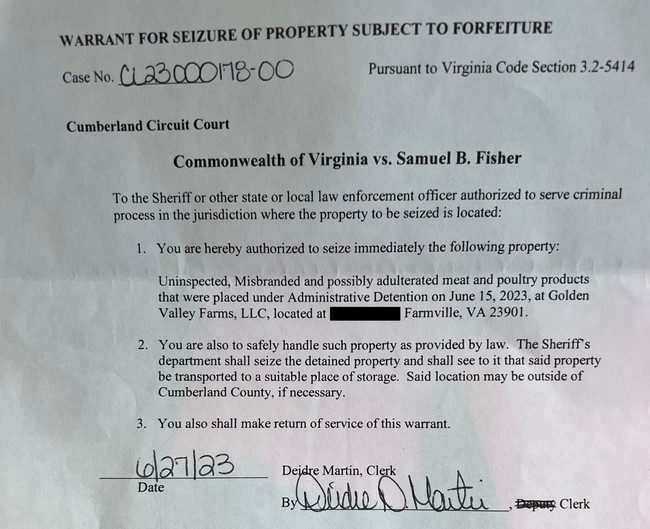

That's when the state took Fisher to court, escalating the meat's preliminary detainment to a court-ordered seizure.

State's warrant to seize Fisher's property | Cumberland County Circuit Court record

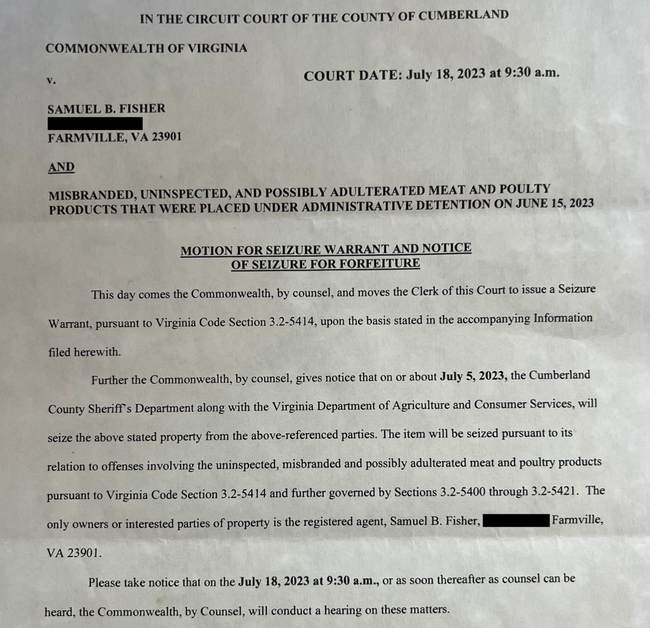

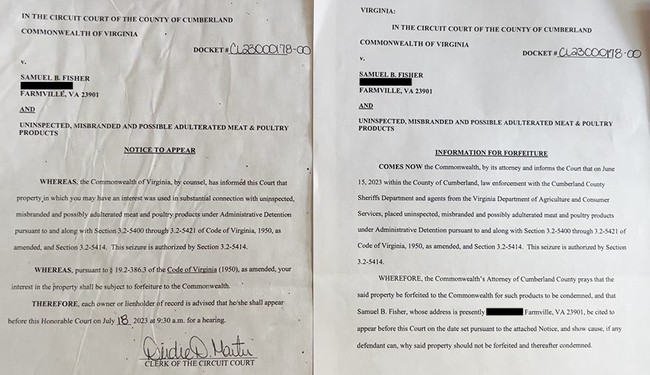

After photographing every square-inch of the farm, stockpiling pictures as evidence that the Fishers were slaughtering and selling raw meat, which the Commonwealth of Virginia claimed was "mislabeled, uninspected, and possibly unadulterated," the state summoned the farmer to a forfeiture hearing on July 18 in Cumberland County Circuit Court to try the civil case. At its conclusion, Chief Judge Donald C. Blessing, after swiftly refusing to grant Fisher a continuance, authorized the state to seize and forfeit the farmer's meat. "He [the judge] did treat me roughly because I asked for a continuance [...] I tried to be silent and he got pretty fired up on me," Fisher recollected from the scene inside the Cumberland County courthouse, off of Anderson Highway.

State summoning Fisher to court for the forfeiture hearing | Cumberland County Circuit Court record

Later that day, the state wasted no time pouncing on the court's order with glee. Within hours, two men backed a U-Haul truck right up to Fisher's door, cleared the premises of Golden Valley Farms meat products, and hauled it all to the dump for disposal.

State's notice to appear in-court | Cumberland County Circuit Court record

"We had all this meat. We worked hard to get it in the freezer, process it, package it, stack it in there to sell and bring income. And, here comes the state, puts everything in their truck, and takes it to the dump, pays us nothing for it, so that definitely affects our income. We do have a big struggle to pay our bills right at the moment," Fisher reflected, citing a temporary stoppage of cash flow when his meat sales were shut down and the dumping of inventory, evaluated to have been worth thousands of dollars.

Aside from the civil charges, Fisher was also criminally charged and accused of violating state law, specifically Virginia Code 29.1-521(A)(10). And, on Aug. 3, Fisher was found guilty of "unlawfully possessing, selling, and/or transporting animals," a Class 3 misdemeanor in Virginia, and forced by a Cumberland County criminal court to pay a fine as punishment for the violation.

Though the future is uncertain, Fisher is considering next steps, including consulting with attorneys, if the state seeks to continue targeting him and Golden Valley Farms. When asked if he fears the feds launching a larger-scale government response, Fisher stressed that since he doesn't ship beyond state lines, although out-of-state customers physically pick up the products and take the meat home themselves, the situation wouldn't warrant federal intervention or USDA involvement. "So, the federal government got nothing here. It's just the state. It's just a matter of time to see if they are going to come out again," the farmer replied.

There are striking parallels between Fisher's case and that of Amos Miller in Bird-in-Hand, Pennsylvania, whose century-old organic Amish farm was repeatedly under attack by the USDA concerning its non-conforming practices that pre-date the federal agency. Similar to Fisher, Miller serves a private-member assocation and raises livestock "the way nature" and "our father God intended": chemical, cruelty, and GMO-free, without antibiotics or hormones, and grown under traditional time-honored methods.

"He's Amish. We come from the same religion," Fisher noted. "I used to live a few miles from his farm. They keep challenging him. I just believe the bigger the farmer is, the more he sells, the harder they're [the government] going to [...] challenge him."

In contact with Miller, Fisher said that he referred him to Max Kane of FarmMatch, an online marketplace that connects buyers with non-toxic regenerative farms in the area on a mission to "decentralize" and "disrupt" the food system through supporting small farmlands. "Kane advised me to sell the meat. He advised me to totally ignore them and just keep on going. 'You're doing the right thing. You're selling good quality food. You have to keep going because people are depending on this stuff as their medicine, because they buy food at the store and their children or somebody gets sick and their diseases get worse.' And then, they started buying my food and their diseases were going away. Now, if I stop, they can't get this food anymore," Fisher said.

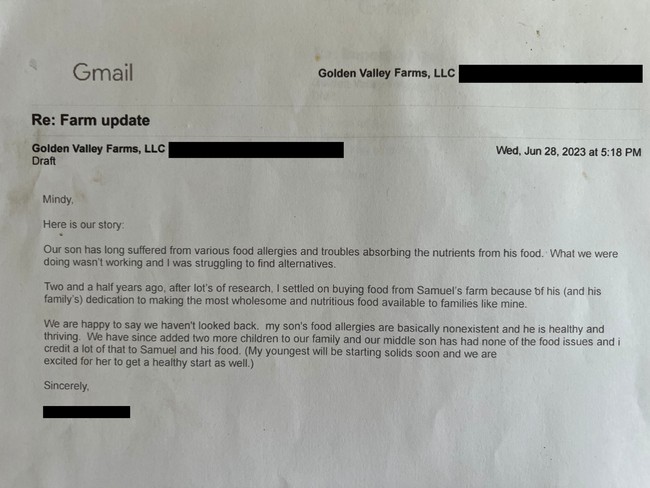

Like Miller, Fisher is one of many targets in the government's wars of attrition that subject fiercely independent farmers to shock-and-awe judicial proceedings. Unsanitary conditions were not found at Golden Valley Farms and no one has ever fallen sick from the meat. Quite the opposite. The meat is "medicine" to many customers with allergies and medical conditions, who've claimed that their ailments were alleviated after switching to Fisher's chemical-free, nutrient-rich, and farm-certified organic food.

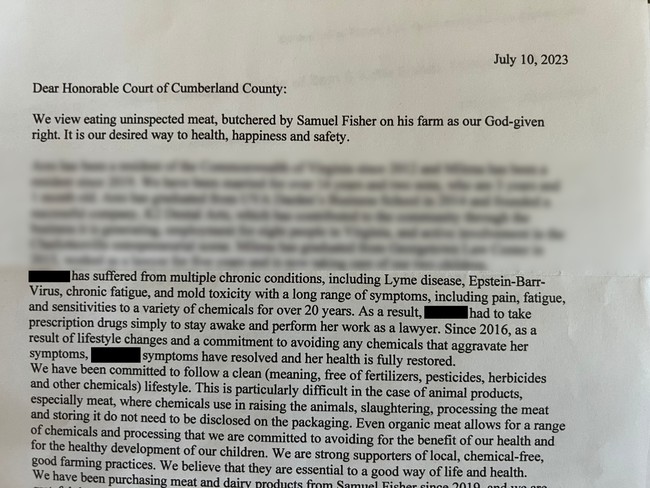

Backed by a loyal customer base, Fisher has received an outpour of support from consumers, who've written testimonies, including letters to the judge presiding over Fisher's civil case, attesting to the high-quality and medicinal effects of his products. And, when the Fishers were away in Pennsylvania, faithful Farmville-area customers poured out to the farm to protect the property, in case anybody else interfered with the business. "Because of the huge customer support, I know I got support here. I know I got people who will stand with me to help me find a way that we can process food the way we want it," Fisher remarked.

(If Farmville sounds familiar, that's the hometown of country-music sensation Oliver Anthony, whose working-man anthem "Rich Men North of Richmond" became a rallying cry for blue-collar workers who are sick of the little guy always being stomped on by the powers that be: "Lord knows they all just wanna have total control / Wanna know what you think, Wanna know what you do.")

Golden Valley Farms customer's letter to the Cumberland County Circuit Court judge

Fisher once sold USDA-inspected meat, but that was before the government-mandated shutdowns, when access to the nearest USDA processor became burdensome during the COVID-19 pandemic. Still, pre-pandemic, the drive was hours away and the cost was hefty, depending on the lot. For example, a trailer load holding four cows and five pigs would be priced at $500, he estimated. It was cumbersome to ship so many animals at one time, process the shipment, and retrieve the meat to have in stock. Hence, it was more practical to process the meat products individually on the farm in order to balance out the inventory and ensure that everything was available, Fisher said. By the time the meat came back from a USDA processor, "you might be running low on certain cuts," he added. Plus, the pandemic meant "you'd have to schedule your animals around eight to 12 months ahead of time," making the timing, and how much meat that needed to be processed, hard to predict so far in advance.

"Stores weren't open. Stores were running out of food. Customers were starting to buy heavily. All of a sudden, we had a lot of need for meat. Well, there was no option taking it to a USDA facility at that time. So, that's when the trigger pushed us to do it ourselves [...] We put an addition to the building and made a processing room and we certainly like it now," Fisher stated.

"Amish people—They don't follow the rules. That's the point," Mindy said. "So, it shouldn't be a surprise to somebody that an Amish person is not following the rules. They opt out of everything. They don't send their kids to school. They don't have to be involved in the [military] draft. They don't pay into the Social Security system and they don't receive money from the Social Security system. Why would anybody think it'd be a stretch that he wasn't getting his meat inspected by the government, too?"

"He thought he can do it himself, so why not do it himself?" Mindy questioned. "And, you know, these people that are buying from him, they're choosing to not buy USDA-inspected meat. That's their choice. They're adults. They can make choices like that."

In fact, a survey was sent to Fisher's customers, asking if they'd prefer the meat to be USDA-inspected or processed here himself. The poll came back overwhelmingly in support of the latter—92% of customers wanted Fisher to process on the farm. "It was very obvious: Customers do want the meat that is processed here on the farm and no USDA inspection," Fisher observed.

Asked why he's become the local go-to source for meat over big-box retailers, Fisher responded: "Oh, because it's a huge differs. If you go to the store, you don't know what's in your food." Fisher went on to describe how, elsewhere in the industrial meat-processing world, whole carcasses of animals are sometimes shipped in, partly rotten and emitting a putrid odor. Assembly-line workers dip the meat into a strong chloride, as a chemical preservative, to manufacture a red, pinkish look "just like it be fresh."

In recent years, medical research has discovered that human ingestion of sodium nitrites and nitrates, oft-used as artificial preservatives and coloring agents in meat, poses a carcinogenic risk to consumers, with links to leukemia and colorectal cancer.

The same goes for soy. Oftentimes, the cause of soy-sensitive consumers, who are allergic to soy, reacting to eggs, dairy products, and flesh meat is the soy residues from soy-based chow that's fed to poultry, also known as secondhand soy transferred via animal feed. "Soy is a cheap product. [Poultry] processors use soy in almost any food they make, 'cause it's cheap," said Fisher, whose chickens are raised without a soy-derived diet. "And now, people are having soy allergies."

Golden Valley Farms customer's letter praising Fisher's products

"And, they send it off to the people. They don't care if people get sick or what happens, because you can't track it," Fisher explained. "If you buy stuff from a store, you can't track where it comes from [...] So, that's why I say if you buy food from a farm, go to that farm, ask the farmer, you want to see their animals, you want to see the farm, you want to know where your food comes from. You do have the full rights to ask for that. If you are not given it, take it as a warning..." he advised. "We believe the healthier your animal is, the healthier the people are who drink the milk or [eat] the meat...from the animals we feed on the farm."

"I want this world to have the opportunity of finding raw, real food, because I've seen what you're buying at the store," Fisher said.

"I don't really know, to the far extent, why they think everything has to be under their jurisdiction, how things are processed, but they like control," Fisher said of the state. "At the same time, I do believe they, in some sense, do care about sanitation and how their foods are processed. So, I do think, in one sense, they are trying to take care of their customers, but they do not have the experience or the education of chemicals, of GMOs [genetically modified organisms]. The way the modern-day processes things is not healthy for your body and they do not seem to care or believe in that. So, to come out here and see it done in a small way, with no inspection, for some reason, they don't like that. I don't really know why they should care too much, if it don't go out to the public, if it just goes to my membership [...] But we do know they like to have jurisdiction over everything they possibly could."

Golden Valley Farms has since launched a GiveSendGo fundraising campaign to support the Fisher family's recovery as the farm rebuilds what the government of Virginia destroyed. Fisher approximates that $10,000 in products was confiscated and dumped.

Editor's Note: Townhall's investigative reporting exposing government overreach would not be possible without the support of our VIP members.

Join Townhall VIP and use promo code INVESTIGATE to support the vital work of Mia Cathell and help us continue to shed light on the infringement of freedom in America.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member