Some people might think that sitting high up in the end zone of a college football stadium is not a good place to watch a game. They would be wrong.

The ultimate strategic goal of every football team in every game they play is simple: Score more than the other team.

That makes the goal line and the goal post the key locations on the field -- and both sit at the end of the field. To score, a team must either put the ball across the goal line or kick it through the uprights.

To accomplish either, it needs to engage in offensive maneuvers designed, play by play, to move the ball toward its opponent's goal line.

A fan sitting on the 50-yard line whose position requires him to look across the field does not see the game from the same perspective as the players moving up and down it.

A fan sitting in the end zone can see each play, and the defense against it, unfold or fail to unfold as they were actually designed.

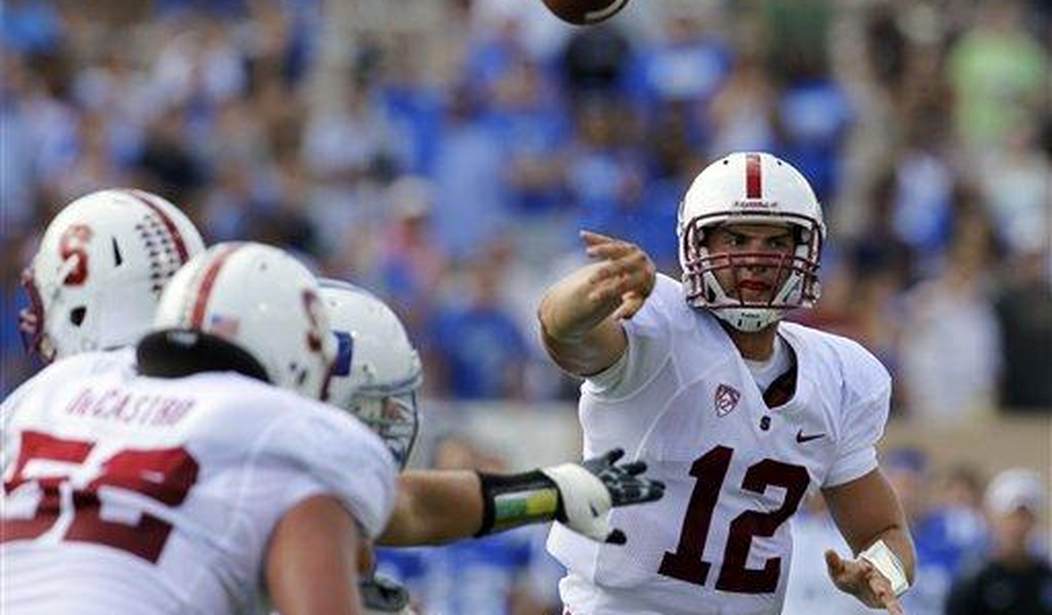

When I was growing up, my father brought me and other family members to every Stanford University Cardinal home game, where we usually sat high in the north end zone of Stanford's old stadium. There we saw great quarterbacks -- including the Heisman Trophy winning Jim Plunkett -- lead Stanford teams to memorable victories.

When Stanford was not playing at home on a fall Saturday, we would go see the University of California Bears play at Memorial Stadium in Berkeley.

And one game we never missed was the Big Game, when Cal and Stanford played each other.

Thus, on the Saturday before Thanksgiving in 1982, when I was a year out of college and was living with my parents in the Bay Area, I went with my father to see John Elway's Stanford team play Cal at Memorial Stadium.

Recommended

We sat high in the south end zone. To our left was San Francisco Bay; to our right, the Berkeley hills; and straight ahead, the field of play.

It was there that we saw Cal make a classic mistake in the closing minutes of the game -- and Stanford's John Elway take advantage of it.

As summarized in Tyler Bridges' book, "Five Laterals and a Trombone: Cal, Stanford, and the Wildest Ending in College Football History," Cal was leading 19-17 with less than three minutes to go when Elway fumbled the ball and Cal recovered it.

"The Bears took over on their own 37 with 2:32 left in the game," wrote Bridges. "Stanford had all three of its timeouts. The Bears needed one first down to win the 85th Big Game, deny Stanford a bowl game invitation, and send Elway back to Palo Alto with a loss in his final collegiate game. It was going to be just a matter of time before the Bears ran out the clock and celebrated a sweet victory."

Or so it seemed.

What did the Bears do? They ran the ball three times, worrying more about the clock itself than getting a first down. Stanford called timeouts after the second and third downs and, as Bridges reports in "Five Laterals and a Trombone," Cal ended up facing a fourth and 2 on their own 45 with 1:43 on the clock.

Cal then punted, giving Stanford and John Elway a chance to win the game.

One short pass in that series might have given Cal a first down and, thus, four more downs and the ability to kill the clock and win the game without giving the ball back to Stanford. But Cal's approach was too conservative for that.

Three downs later, however, the Cardinal was in a dire situation. "Stanford faced fourth and 17 on its own 13-yard line, trailing 19-17. Only 53 seconds remained," wrote Bridges.

Elway evaded Cal's pass rushers and completed a pass to receiver Emile Harry. "It was a 29-yard gain and a first down!" Bridges wrote. Elway then completed another pass to receiver Mike Tolliver, and Stanford had the ball at Cal's 39-yard line.

Then Stanford -- still with one timeout left -- did something shocking: It ran the ball, and running back Mike Dotterer took it all the way to the 18-yard line.

Then Stanford ran Dotterer again, who was tackled immediately.

That is when Stanford made the opposite mistake Cal had made: It did not worry enough about the clock.

An article published in 2002 in Stanford Magazine described it this way: "But with the clock winding down, Elway made what at the time seemed an insignificant mental error: he called timeout with 8 seconds remaining. This guaranteed that the game would not end with Stanford's ensuing field-goal attempt. Yet when kicker Mark Harmon drilled a 35-yard field goal a moment later to put Stanford ahead, 20-19, he recalls thinking, 'I just won the Big Game!'"

"But the game clock had four seconds remaining," Stanford Magazine explained.

What happened in those four seconds?

Stanford sent a squib kick down field. The Cal return team lateraled the ball five times -- with the third lateral being made by a player who arguably was already down.

With the Stanford student band running through the south end zone onto the field in an ill-timed celebration, Cal's Kevin Moen, who had been the first to field the kick and first to lateral it, took the last lateral and ran the ball into the end zone where he collided with a Stanford trombone player.

The referees ruled it a touchdown. Cal won.

Had Stanford simply waited four seconds to call its last time out, Cal would not have had the four seconds it needed to win the game.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member