Editors' note: This article is a free preview from the February issue of Townhall Magazine. Click here to subscribe and receive a free copy of Ann Coulter's new book, Guilty.

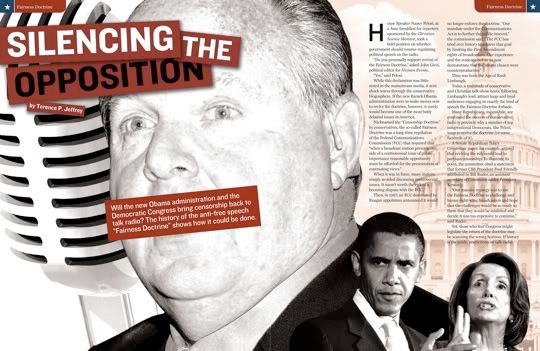

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, at a June breakfast for reporters sponsored by the Christian Science Monitor, took a bold position on whether government should resume regulating political speech on the radio.

“Do you personally support revival of the Fairness Doctrine,” asked John Gizzi, political editor for Human Events.

“Yes,” said Pelosi.

While this declaration was little noted in the mainstream media, it sent shock waves through the conservative blogosphere. If the new Barack Obama administration were to make moves now to revive the doctrine, however, it surely would become one of the most hotly debated issues in America.

Nicknamed the “Censorship Doctrine” by conservatives, the so-called Fairness Doctrine was a long-time regulation of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) that required that “when a broadcast station presents one side of a controversial issue of public importance reasonable opportunity must be afforded for the presentation of contrasting views.”

When it was in force, many stations simply avoided discussing controversial issues. It wasn’t worth the risk of a licensing dispute with the FCC.

Then, in 1987, an FCC dominated by Reagan appointees announced it would no longer enforce the doctrine. “Our mandate under the Communications Act is to further the public interest,” the commission said. “The FCC has tried over history to achieve that goal by limiting the First Amendment rights of broadcasters. Our experience and the evidence before us now demonstrate that the means chosen were counterproductive.”

Thus was born the Age of Rush Limbaugh.

Today, a multitude of conservative and Christian talk-show hosts, following Limbaugh’s lead, attract large and loyal audiences engaging in exactly the kind of speech the Fairness Doctrine forbade.

Many Republicans, meanwhile, are convinced the success of conservative radio is precisely why a number of top congressional Democrats, like Pelosi, want to revive the doctrine (or some facsimile of it).

A Senate Republican Policy Committee paper, for example, argued that reviving the rule could lead to partisan censorship. To illustrate its point, the committee cited a statement that former CBS President Fred Friendly attributed to Bill Ruder, an assistant secretary of Commerce under President Kennedy.

“Our massive strategy was to use the Fairness Doctrine to challenge and harass right-wing broadcasters and hope that the challenges would be so costly to them that they would be inhibited and decide it was too expensive to continue,” said Ruder.

Yet, those who fear Congress might legislate the return of the doctrine may be scanning the wrong horizon. If history is the guide, restrictions on talk-radio speech are more likely to come directly from the unelected FCC.

That is where the Fairness Doctrine came from in the first place.

REPEATING HISTORY

Recent events, in fact, resemble those of eight decades ago, when Congress, regulating radio for the first time, declined to give federal radio commissioners authority to regulate programming—and the commissioners did it anyway.

First, the recent history: In 2007, Republican Mike Pence of Indiana, in an apparent demonstration of strength by Fairness Doctrine opponents, offered an amendment to deny funding to the FCC to enforce the doctrine in fiscal 2008. It passed 309-115.

A few weeks later, Republican Sen. Norm Coleman of Minnesota offered a similar amendment. This time, Senate Democratic Whip Dick Durbin of Illinois objected.

Recommended

Coleman argued that the free market, not government, was the best mechanism for providing balance in broadcasting. Durbin rejected the notion that the free market applies to radio.

“What is the senator’s response if the marketplace fails to provide? What if it doesn’t provide the opportunity to hear both points of view?” said Durbin. “Since the people who are seeking the licenses are using America’s airwaves, does the government, speaking for the people of this country, have any interest at that point to step in and make sure there is a fair and balanced approach to the information given to the American people?”

Sixty votes were needed to force a substantive vote on Coleman’s amendment. It got 49.

The Coleman-Durbin debate of 2007 could have been lifted from the Congressional Record of 1927.

Up until then, American broadcasting was governed by the Radio Act of 1912, which was designed to ensure good communications with ships at sea, then the primary users of radio. It gave government no power to deny a broadcasting license to anyone.

In the 1920s, the number of broadcast stations exploded, clogging the limited frequencies available, interfering with each other’s signals. Radio was gagging on its own success.

A 1925 conference convened by Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover recommended new legislation to regulate the airwaves. Republican President Calvin Coolidge backed the recommendation, and Maine Republican Rep. Wallace White took up the cause in the House.

In a 1926 floor speech, White explained that his radio bill was designed to preserve the freedom of speech and property rights of broadcasters while serving the broader “public interest.” In his view, the “public interest” meant restraining government, not broadcasters.

“We are dealing here with a new means of communication,” said White. “It is fighting to develop its usefulness in a field in which telephones, telegraphs and cables are entrenched. We should exercise every care in the public interest, but there exists a reasonable doubt whether we are justified in applying to this industry different and more drastic rules than the other forms of communication are subjected to.”

The first person to question White on the House floor was New York Republican Rep. Fiorello La Guardia, who had one issue on his mind: preserving freedom of speech.

“The pending bill gives the secretary no power of interfering with freedom of speech in any degree,” White told La Guardia.

“It is the belief of the gentleman and the intent of Congress in passing this bill not to give the secretary any power whatever in that respect in considering a license or the revocation of a license,” said La Guardia.

“No power at all,” responded White.

Rep. Luther Johnson, a Texas Democrat, was unhappy about this. He offered an amendment instructing broadcasters that “equal facilities and rates, without discrimination, shall be accorded to all political parties and all candidates for office, and to both the proponents and opponents of all political questions or issues.”

It was ruled not germane. The bill that the House sent to the Senate gave the government no power to regulate political speech on the radio.

SENATE FIGHT OVER SPEECH

In the Senate, there was a bloc that did want to regulate political speech on the radio.

Contrary to the views of the Senate sponsor, Washington Democrat Clarence Dill, the Senate Committee on Interstate Commerce produced a bill that said: “If any licensee shall permit a broadcasting station to be used … by a candidate or candidates for public office, or for the discussion of any question affecting the public, he shall make no discrimination as to the use of such broadcasting station, and with respect to said matters the licensee shall be deemed a common carrier in Interstate commerce: Provided, that such licensee shall have no power to censor the material broadcast.”

The practical effect of this provision would have been that any station that allowed any discussion of a public issue would have been required to allow access to all comers to say anything they wanted about that issue.

Dill took the Senate floor intent on removing this provision. He argued for free-market radio.

“First and most important of all, radio in the United States is free,” said Dill. “In practically all other countries, the government either owns or directly controls all broadcasting stations. In this country, there has been practically no control exercised by the government, except as to the assignment of wave lengths and regulations as to the amount of power to be used. What has been the result of this policy of freedom for radio broadcasting and radio reception? The result is that American initiative and American business ingenuity have developed radio broadcasting in the United States far beyond anything known in other parts of the world.”

Dill offered an amendment to strip the bill of the language that said broadcasters could not discriminate between points of view in “the discussion of any question affecting the public.” However, his amendment maintained an equal-time rule for political candidates.

Nebraska Republican Sen. Robert Howell objected to Dill’s amendment. “To perpetuate in the hands of a comparatively few interests the opportunity of reaching the public by radio and allowing them alone to determine what the public shall and shall not hear is a tremendously dangerous course for Congress to pursue,” said Howell. “If both sides of a question cannot be heard over a particular radio station, none should be heard.”

Dill countered by predicting that if Howell’s version of the legislation were enacted, that is exactly what would happen. “[T]here is probably no question of any interest whatever that could be discussed but that the other side of it could demand time,” said Dill, “and thus a radio station would be placed in the position … that they would have to give all their time to that kind of discussion, or no public question could be discussed.”

Congress sided with Dill, not Howell. The Radio Act of 1927 required broadcasters to give “equal opportunities” to candidates but not to opposing sides of public issues. It expressly denied regulators “the power of censorship” or the authority to “interfere with the right of free speech” on the radio.

It also instructed federal regulators to use the general standard of “public interest, convenience, or necessity” when granting, renewing or modifying broadcast licenses.

Editors' note: This article is a free preview from the February issue of Townhall Magazine. Click here to sign up and receive Townhall Magazine every month in your mailbox!

IMPORTANCE OF INTENTION

In 1968, the staff of the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce published a study on the “Legislative History of the Fairness Doctrine.” “As enacted by the 69th Congress, the Radio Act contained no provision similar to the Fairness Doctrine,” the study concluded. “This omission seems to have been specifically intended.”

Initially, the Federal Radio Commission (FRC) created by the 1927 act saw it that way, too. Its first report to Congress included a speech by Commissioner Henry Bellows.

“Very rightly Congress has held that the broadcaster shall not be subject to government dictation as to the character of the material he sends out: The Federal Radio Commission under the present law cannot and will not interfere with any broadcaster’s right to control and censor his own programs,” said Bellows. “In that matter, his relations are not with the government, not with the commission, but with you. It is for you, the listeners, not for us, to censor his programs. It is for you to tell him when he is rendering, or failing to render, real service to the public, and you may be sure he will listen to your voices.”

While Bellows expressed concern that “the newcomer, the nonconformist, the representative of the minority” might not fi nd a voice on the air because of the limited number of broadcast licenses available, he also said the law gave the FRC no power to deal with this potential problem.

If listener feedback did not cause broadcasters to provide a broad range of programs, Bellows said, “then it may be that Congress will feel that there is a need for some amendment to the present radio law, an amendment calling for such government regulation of radio programs as would manifestly be deplorable if it can possibly be avoided.”

Congress passed no amendment. But two years later, in the case of Great Lakes Broadcasting Co., the FRC unilaterally adopted precisely the sort of regulation of speech Congress had rejected—using the law’s vague “public interest” standard to justify the move.

“Insofar as a program consists of discussion of public questions,” the commission said, “public interest requires ample play for the free and fair competition of opposing views, and the commission believes that the principle applies not only to addresses by political candidates but to all discussions of issues of importance to the public.”

In the same case, the FRC said it intended to discriminate against radio stations “operated by religious or similar organizations.”

“Certain enterprising organizations, quick to see the possibilities of radio and anxious to present their creeds to the public, availed themselves of license privileges from the earlier days of broadcasting and now have good records and a certain degree of popularity among listeners,” said the Great Lakes ruling. “The commission feels that the situation must be dealt with on a commonsense basis. It does not seem just to deprive such stations of all right to operation, and the question must be solved on a comparative basis. While the commission is of the opinion that a broadcasting station engaged in general public service has, ordinarily, a claim to preference over a propaganda station, it will apply this principle as to existing stations by giving preferential facilities to the former and assigning less desirable facilities to the latter to the extent that engineering principles permit.”

In 1934, when Congress replaced the Radio Act with the Communications Act (which currently governs radio regulation), it again had an opportunity to authorize regulation of programming content. It declined to do so.

The Senate passed language in the 1934 bill that required broadcasters “to permit equal opportunity for the presentation of both sides of public questions.” The House did not. As enacted, the 1934 law preserved Sen. Dill’s 1927 amendment verbatim. “Equal opportunities” were required for political candidates but not for opposing views on public issues.

The 1968 congressional study on the legislative history concluded: “The enactment of the Communications Act in the 73rd Congress provided another instance wherein language similar to the present Fairness Doctrine was unsuccessfully proposed for incorporation into the law.”

Nonetheless, the FCC, which under the 1934 law replaced the FRC, advanced the FRC’s vision for regulating content.

In 1941, a potential competitor sought a license to take over the frequency used by WAAB in Boston, which the FCC found had broadcast editorials “from time to time urging the election of various candidates for political office or supporting one side or another of various questions in public controversy.”

The FCC renewed WAAB’s license but warned that a broadcaster could not operate a station “devoted to the support of principles he happens to regard most favorably.”

“In brief,” said the FCC, “the broadcaster cannot be an advocate.”

It should be noted that this sweeping regulatory ruling came down at a time when a single party had controlled the Congress and White House for eight years.

FORMAL PRONOUNCEMENT

It was not until eight years later that the FCC modified its position by issuing a follow-up opinion on the question of “whether the expression of editorial opinions by broadcast station licensees on matters of public interest and controversy is consistent with their obligations to operate their stations in the public interest.”

Here the Fairness Doctrine was formally pronounced. It was OK for stations to editorialize, said the FCC, but the public interest “requires that licensees devote a reasonable percentage of their broadcasting time to the discussion of public issues of interest in the community served by their stations and that such programs be designed so that the public has a reasonable opportunity to hear different opposing positions on the public issues of interest and importance in the community.”

Ten years later, the issue came up in Congress again. The FCC ruled that a broadcaster that gave exposure to a politician in routine news coverage must give equal time to rival candidates. Congress—full of incumbents likely to gain exposure in routine news coverage—sought to overrule this.

Again, there was disagreement about codifying a requirement that broadcasters also air opposing sides of public issues. In 1959, the exemption to the candidate equal-time rule Congress finally approved warned broadcasters that it did not exempt them “from the obligation imposed upon them under this act to operate in the public interest and to afford reasonable opportunity for the discussion of conflicting views on issues of public importance.”

The meaning of this provision was disputed. Like the 1968 staff of the Interstate Commerce Committee, author Steven J. Simmons studied the legislative history of the Fairness Doctrine. “Whether by congressional mandatory compulsion on licensees or by congressional authorization of FCC mandatory compulsion on licensees, it is obvious that Congress in 1959 was approving the commission’s Fairness Doctrine,” Simmons wrote in his 1978 book, “The Fairness Doctrine and the Media.” “If the amendment compels the fairness doctrine, then the FCC cannot remove it without congressional approval. … If, by the 1959 amendment, the Commission is simply authorized, and not compelled, to impose the doctrine, then the Commission could indeed suspend its enforcement if it deemed this to be in the public interest.”

RULED ‘CONSTITUTIONAL’

In the 1969 case of Red Lion Broadcasting v. FCC, the Supreme Court ruled that the Fairness Doctrine was constitutional. In the 1986 case of Telecommunications Research and Action Center v. FCC, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia settled the dispute on the meaning of the 1959 amendment.

“We do not believe that language adopted in 1959 made the Fairness Doctrine a binding statutory obligation; rather, it ratified the commission’s longstanding position that the public interest standard authorizes the Fairness Doctrine,” said the court. “The language, in its plain import, neither creates nor imposes any obligation, but seeks to make it clear that the statutory amendment does not affect the Fairness Doctrine obligation as the commission had previously applied it.” The opinion was written by Judge Robert Bork, and joined by Judge Antonin Scalia.

As far as the courts were concerned, the Fairness Doctrine was constitutionally permissible, but not statutorily mandated. That is how the law stood in 1987 when the FCC exercised its discretion to stop enforcing the doctrine, and that is how it stands today.

Editors' note: This article is a free preview from the February issue of Townhall Magazine. Click here to subscribe and receive a free copy of Ann Coulter's new book, Guilty.THE GOAL: WEAKEN RIGHT-WING SPEECH

Today’s congressional opponents and proponents of the Fairness Doctrine have reached a stalemate, but that does not mean the FCC cannot take steps that, without actually re-imposing the doctrine, can achieve the same end: diminishing the conservative presence on radio.

After his one-year funding moratorium passed in 2007, Rep. Pence introduced a bill to permanently prohibit the FCC from reviving the doctrine. When the Democratic leadership refused to bring it up, Pence started a “discharge petition” that if signed by 218 members would have forced a vote. It garnered only 202.

This year, Pence has joined with Republican Sen. Jim DeMint, S.C., to reintroduce his bill. But in a Congress that has a larger Democratic majority, it will not see the light of day.

The experience of Rep. Maurice Hinchey, a New York Democrat who sponsored a bill to revive the Fairness Doctrine, illustrates the problem for its proponents. When Hinchey appeared on Tucker Carlson’s MSNBC program in 2007 to defend his proposal, he ended up defending the right of Holocaust deniers to be heard on TV.

“So, I’m required to put a holocaust denier on?” asked Carlson.

“Any particular point of view that you have, if somebody has an alternative point of view, then there is a responsibility to give that point of view an opportunity to be heard,” said Hinchey.

Supporters of legislatively mandating the Fairness Doctrine risk putting themselves in a politically untenable position.

“Obama is way smarter than that,” conservative writer Jack Thompson noted in a November column in Human Events.

So is John Podesta, who led Obama’s transition team, whom conservative critics such as Thompson and other close observers of the Fairness Doctrine debate believe has already laid out an alternative strategy for censuring talk radio.

Podesta, a former Clinton White House chief of staff, is president of the Center for American Progress (CAP). In 2007, CAP published a study detailing the policy steps needed to reverse conservative domination of talk radio. It neither rejected nor recommended resurrecting the Fairness Doctrine.

But it did argue that the free market does not work in radio.

“When 91 percent of the talk radio programming broadcast each weekday is solely conservative—despite a diversity of opinions among radio audiences and the proven success of progressive shows—the market solution has clearly failed to meet audience demand,” said the CAP study.

CAP said its study showed “that stations owned by women, minorities or local owners are statistically less likely to air conservative hosts or shows,” while “stations controlled by group owners— those with stations in multiple markets or more than three stations in a single market—were statistically more likely to air conservative talk.”

HOW OBAMA COULD SQUELCH TALK RADIO

To increase “progressive” talk and decrease conservative talk, CAP recommended capping the number of stations any organization can own, increasing the percentage of stations owned by women and minorities, shortening the lifespan of broadcasting licenses from eight years to three, and compelling licensees to show they are serving the local “public interest.”

Could an Obama administration do this?

The FCC has fi ve commissioners appointed by the president, who chooses the chairman from among them. No more than three can be from one party. The commission is now missing a Republican member whose term expired. Obama can immediately name a Democrat to fi ll the vacancy, securing a Democratic majority, and elevate one of the Democrats to the chairmanship.

Obama spokesman Michael Ortiz told Broadcasting & Cable last year that Obama does not favor the Fairness Doctrine, considering discussion of it “a distraction from the conversation we should be having about opening up the airwaves and modern communications to as many diverse viewpoints as possible.” Ortiz mentioned “media-ownership caps” and “increased minority ownership of broadcasting and print outlets” as things Obama did support.

In a 2007 letter to the FCC, Obama criticized the commission because he believed it “failed to further the goals of diversity in the media and promote localism.

Obama’s team may be preparing not to censor Rush Limbaugh but to have the FCC transfer broadcast licenses to station owners who will hire someone else in his place.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member