The rumble of history is returning to Baghdad. With Iraq’s dominant Shi’ite Coordination Framework nominating Nouri al-Maliki as its candidate for prime minister, the nation stands on the brink of a moment that could reshape its trajectory at home and abroad. Maliki, Iraq’s most polarizing statesman since the 2003 invasion, is poised for a political comeback that has left Washington jittery, Tehran hopeful, and Iraqi Sunnis, Kurds and civil society fearful of a return to the sectarian politics that once tore the country apart.

On Sunday, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio telephoned incumbent Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani with a blunt message. Iraq must not allow itself to become a puppet of Iran again! Rubio emphasized that “a government controlled by Iran cannot successfully put Iraq’s own interests first, keep Iraq out of regional conflicts, or advance the mutually beneficial partnership” between Washington and Baghdad.

This is not just diplomatic rhetoric. The U.S. holds considerable leverage over Iraq, including the lion’s share of its oil export revenues, which are still managed through accounts at the U.S. Federal Reserve in New York, a vestige of post-2003 economic arrangements that grant Washington powerful financial influence. The Rubio warning also resonates against a backdrop of fiery U.S./Iran tensions. Iran’s theocratic regime has been battered by a nationwide uprising and regional setbacks, including the collapse of its alliance with Bashar al-Assad in Syria. In that vacuum, Tehran sees an Iraqi government sympathetic to its worldview as a rare strategic gain.

For Iraq’s Sunnis and Kurds, Maliki’s name is not just familiar, it’s intolerable. Maliki first became prime minister in 2006, with U.S. support, during the apogee of the Iraq conflict. He initially backed U.S. efforts against Sunni militants, but his legacy quickly soured. Accusations of deepening sectarian divisions, marginalizing Sunnis and even consolidating power through patronage and security crackdowns abounded. Many analysts argue that Maliki’s exclusionary governance helped lay fertile ground for the rise of ISIS in 2014. Under his two terms, Iraq fractured along identity lines. Sunni Arabs felt alienated from authority. Kurdish leaders pursued autonomy amid political deadlock, and Shi’ite militias, some aligned with Iran, grew in influence.

Recommended

During his term, Iraq, in collusion with Tehran, unleashed its military against the Mujahedin-e Khalq (MEK) in Camp Ashraf in Diyala Province. In three lethal attacks, including a ground assault, 101 MEK members were killed and more than 1,000 were wounded. Seven, including six women, were abducted and have never been heard from since.

That period’s politics were defined less by nation-building and more by factional advantage, a legacy that hard-pressed Iraqis have yet to overcome. Critics also point to corruption and Maliki’s close ties with Iran-linked armed groups, links that, in the view of Washington, undermine Baghdad’s sovereignty and fuel regional conflict. These militias have often acted with impunity, operating parallel to the state’s institutions and deepening the fragmentation of Iraqi authority. Maliki’s return must be understood in that regional context.

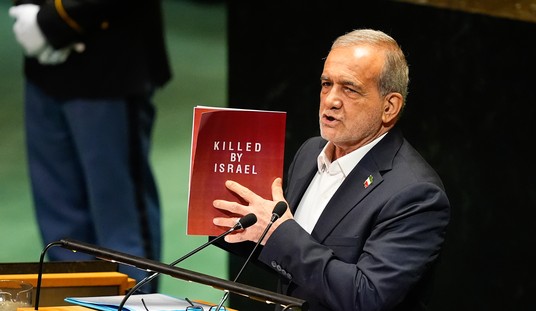

For Tehran, Iraq has long been a strategic prize. Iran’s Revolutionary Guards and allied militias have cultivated deep networks in Iraqi society and security structures. A government that leans toward Tehran could provide Iran with political cover and a buffer against its adversaries, reinforcing a “land bridge” stretching from Tehran through Baghdad to Damascus and beyond. Washington, by contrast, fears that an Iran-aligned Iraq would draw Baghdad into Tehran’s orbit, potentially dragging Iraq into conflicts it should avoid and giving Iran a strategic launchpad closer to the Gulf and wider Arab world. Rubio’s warning reflects this fear, urging Iraq to pursue a genuinely independent foreign policy. The Sunni Arab states, still reeling from years of Iranian influence expanding in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon, view Maliki’s ascendancy with apprehension. Riyadh and Abu Dhabi have invested heavily in countering Tehran’s reach. Seeing Iraq drift back into Iran’s embrace could set back years of diplomatic and economic outreach.

Iraq’s internal political map remains volatile. The Coordination Framework that nominated Maliki includes parties and militia-linked factions with varying degrees of closeness to Iran. Their dominance in parliament reflects the electoral arithmetic, but not unanimous national support. Sunnis and Kurds have voiced serious reservations about Maliki’s candidacy, and there remains a narrow window for compromise that could keep Iraq on a more inclusive footing, potentially even enabling Sudani to retain power. Moreover, Iraqi youths and civil society have repeatedly called for accountability, reform and an end to sectarian politics that have stunted governance and opportunity. Whether Maliki can, or will, address these aspirations is an open question.

If Maliki returns as prime minister, Iraq risks slipping back into the sectarian governance that once fractured the nation. A government perceived as beholden to Tehran may struggle to balance Baghdad’s interests with the broader regional turbulence, fuelling mistrust among Sunni Arabs, emboldening militia groups, and deepening Iraq’s entanglement in the geopolitical rivalries between Washington and Tehran.

Marco Rubio’s warning is not merely a diplomatic flourish; it’s a stark reflection of how seriously Washington views Iraq’s political direction. For Iraqis, it signals the geopolitical tug-of-war that now defines their national decision-making, between Baghdad’s own sovereign interests and the pressures of external powers, including Iran, the United States, and regional neighbours.

Iraq stands at a crossroads. If its leaders choose the road of factional allegiance over national unity, the consequences will reverberate well beyond Baghdad, deepening sectarian divides at home and entangling its people further in the Middle East’s relentless struggles. If, by contrast, Iraq can find a path to inclusive governance and balanced diplomacy, there remains a chance, however slim, that it might yet emerge as a bridge between competing powers rather than a battleground for them.

The world is watching.

Struan Stevenson was president of the European Parliament's Delegation for Relations with Iraq (2009-14) and chairman of the Friends of a Free Iran Intergroup (2004-14), the Coordinator of the Campaign for Iran Change (CiC). He was a member of the European Parliament (MEP) representing Scotland (1999-2014). He is an author and international lecturer on the Middle East.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member