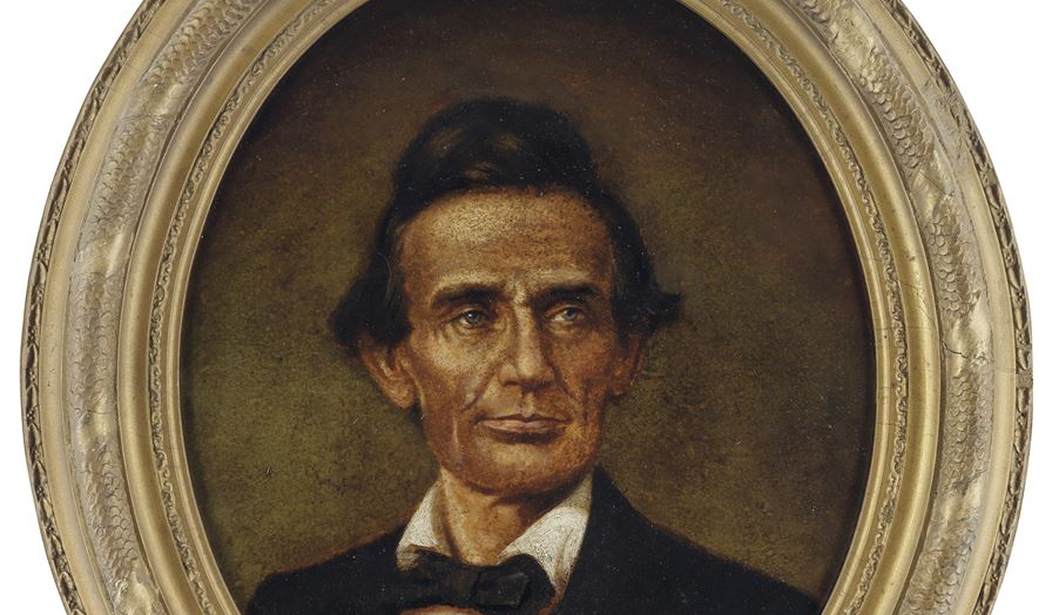

Among the thousands of speeches by American presidents, none is better known and more representative of American democracy than Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, delivered on November 19, 1863.

In a National Public Radio interview in 2013 - the sesquicentennial of Lincoln’s address - historian Eric Foner said that among “The two key ideas in this speech,” was “the principle of democracy: Government of the people, by the people.”

The PBS documentary Lincoln @ Gettysburg, released that same year, included an interview with former Bill Clinton Chief Speechwriter Michael Waldman, who characterized that passage saying, “Lincoln, to this day, has given us the most concise, telegraphic and basic definition of democracy: Government of the people, by the people, and for the people."

Another 2013 piece in Politico waxed eloquent, proclaiming the speech, “a sacred American text, so fully absorbed into the culture that phrases such as… ‘of the people, by the people, for the people’ are as familiar as any song lyric or line of poetry.”

These modern assessments of the Gettysburg Address and how Lincoln defined the essence of our democratic republic are insightful. But when learning about history, nothing compares with accounts from those who were actually there. That would include Clark Ezra Carr, whose analysis of Lincoln’s address merits considerable weight in the historical record.

Carr was a prominent Illinois Republican who shared the stage with Lincoln that November day 160 years ago as a commissioner on the Select Committee Relative to the Soldiers’ National Cemetery at Gettysburg. He went on to write the book Lincoln at Gettysburg: An Address, first published in 1906.

Recommended

In his book, Carr explains how critics pounced on Lincoln’s use of the ‘government of/by/for the people' line. “The phrase ‘of the people, by the people and for the people’ was not original with Mr. Lincoln,” writes Carr on page 73. “There was considerable comment at the time upon his using it, which went so far that it was insinuated that he was guilty of willful plagiarism.”

Criticism of Lincoln’s use of the phrase and its provenance prompted a speedy damage control response by his allies. Carr reports the passage was “thoroughly investigated,” with the results showing that “the phrase had been so often used as to have become common property,” citing numerous American variations of the phrase between 1825 and 1853, as well as its use in foreign languages.

The plagiarism investigation determined, “The first appearance of it, so far as it has been possible to ascertain, was in the preface to the old Wycliffe Bible, translated before 1384,” with Carr noting, “it is there declared that, ‘this Bible is for the government of the people, by the people, and for the people.”

The “old Wycliffe Bible” to which Carr refers is that of Oxford theologian and scholar John Wycliffe who, in defiance of the theocratic powers of the day, first translated the Bible into English, a capital offense in the 14th century. Wycliffe, who promoted keeping the church separate from the civil government, avoided being burned at the stake for his crime. But the translation so enraged the ruling theocracy, they posthumously declared him a heretic and subsequently exhumed his bones 44 years after his death for the purpose of burning them and scattering the ashes.

NPR, PBS, and Politico all praised the Christian foundation of American democracy and the necessity of biblical precepts in civil society, probably without realizing it. They extolled these virtues in the context of Lincoln’s address, but the words and sentiment they so effusively admired were entirely biblical, enunciated by a radical Christian reformer who proclaimed freedom of conscience, and separate government and church entities - nearly five centuries before Lincoln - and who declared the Bible to be the source of wisdom and guidance for good government.

Liberal commentators will predictably discount this historical record, likely claiming they cannot find any writings by Wycliffe to this effect. But Lincoln’s men found them in 1863. The historical record is sufficient for the University of Delaware’s Gettysburg Address in 2023 Exhibition, which also cites the preface to Wycliffe’s English Bible.

Ironically, Lincoln’s defenders didn’t even need Wycliffe. The damage control team had more than enough examples of common use of the phrase to deflect any partisan accusations of plagiarism. Furthermore, Lincoln’s men had no incentive to promote a ‘Christian Founding’ narrative simply because almost all Americans in the mid-19th century knew that to be true. Adding Wycliffe’s writings to their findings wasn’t gratuitous, it was merely due diligence.

Regardless of how Lincoln’s allies defended him, the fact is more than a few modern, liberal commentators agreed with John Wycliffe’s observation that the Bible is essential to democracy and government of the people, by the people, and for the people. They were just too ignorant to know otherwise, and too intellectually inconsistent today to admit they got it right the first time.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member