On a sunny morning in the summer of 2012, I visited Charlottesville, Virginia (Jefferson’s hometown). My host was a local pastor, Dr. Mark Beliles. He and I were working on a book (Doubting Thomas) on the faith (and sometimes lack thereof) of our third president.

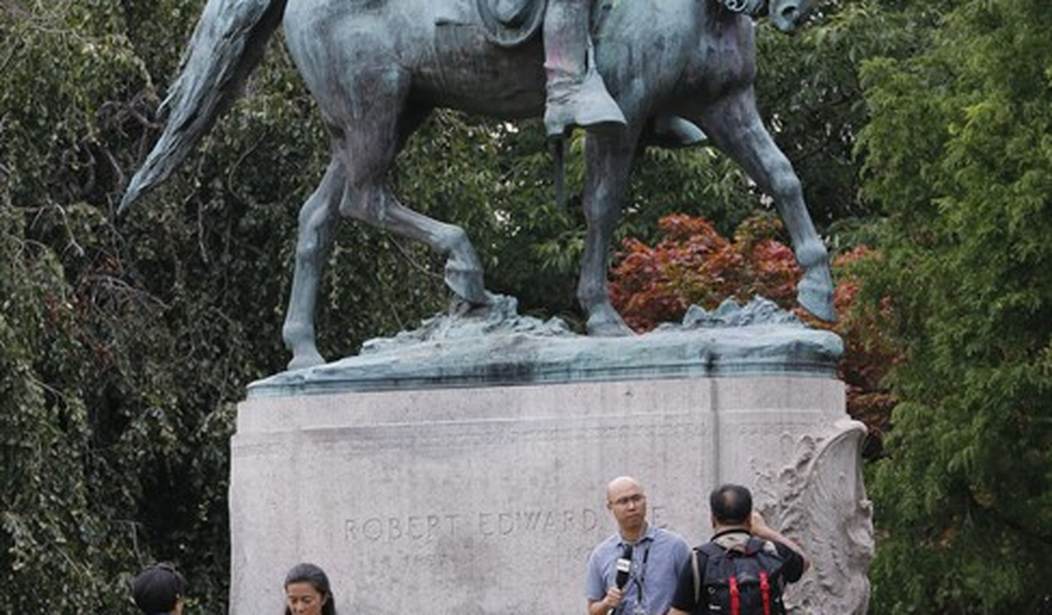

Beliles brought me to two parks downtown on that peaceful day and showed me two statues that he said were shrouded in controversy, although they have stood for a hundred years. They were of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson.

Fast forward to this past weekend, and the scene was anything but peaceful. The protests centered around the Robert E. Lee statue, which apparently is slated to be dismantled.

Protesters for and against the statue clashed in ugly violence. A 20-year old reported Hitler-loving racist from Ohio allegedly drove his car into a crowd of counter-protesters and killed a 32-year old woman and maimed others. Our thoughts and prayers are with the victims and families.

After this awful melee, President Trump said (8/14/17): "… we condemn in strongest possible terms this egregious display of hatred, bigotry and violence. It has no place in America. And as I have said many times before, no matter the color of our skin, we all live under the same laws. We all salute the same great flag. And we are all made by the same almighty God.”

And he added, “Racism is evil. And those who cause violence in its name are criminals and thugs, including the KKK, neo-Nazis, white supremacists and other hate groups that are repugnant to everything we hold dear as Americans.”

Whether Confederate statues should remain in the parks (as opposed to museums) is one issue. But the irony of all the fuss over Robert E. Lee is that the man himself would have been among the first to eschew racism. The real Robert E. Lee is an ironic lightning rod for such violence.

Recommended

In research for this piece, I came across an article from National Geographic News from 2001. Edward C. Smith wrote an opinion piece; “U.S. Racists Dishonor Robert E. Lee by Association.” Hear. Hear. He writes: “Lee, the epitome of the image of the noble, chivalric cavalier, accepted the loss of the quest for Southern independence with extraordinary grace.”

General Lee didn’t fight to preserve slavery. He freed slaves, at great personal cost, that he had inherited by marriage. He hated the “peculiar institution.” He also was in favor of the preservation of the Union and opposed to secession. But when asked by President Lincoln to lead the troops to squash the burgeoning rebellion, he asked, “How can I draw my sword upon Virginia, my native state?”

State’s rights was the ostensible reason men like Lee and Jackson fought for the Confederacy, but clearly the catalyst cause was slavery. This reality is clearly a mark against Lee, Jackson, and others who fought for the South. But we should also remember them for who they actually were, rather than as two-dimensional cutouts in a simplistic morality play of obvious good versus obvious evil.

If we start to tear down all statues of Lee and Stonewall Jackson and Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy, why stop there? What about the nine presidents of the United States who owned slaves? Washington was the only one of those who freed his slaves.

And why stop with just slavery? Didn’t the Union General Sheridan go on to fight Native Americans in the West and to reportedly declare (although he denied it), “The only good Indian I ever saw was dead”? Too many statues. Too little time.

We should be honest about our history, but not try to revise it with a giant eraser, like the “unpersons” in George Orwell’s 1984.

America needs a great revival, where we can honor the past, but not be held captive to it.

In one particular incident after the war, Robert E. Lee himself provides a great example of the kind of change we need in this country going forward. Smith writes: “One Sunday at St. Paul's Episcopal Church in Richmond, a well-dressed, lone black man, whom no one in the community—white or black—had ever seen before, had attended the service, sitting unnoticed in the last pew. Just before communion was to be distributed, he rose and proudly walked down the center aisle through the middle of the church where all could see him and approached the communion rail, where he knelt. The priest and the congregation were completely aghast and in total shock. No one knew what to do…except General Lee. He went to the communion rail and knelt beside the black man and they received communion together—and then a steady flow of other church members followed the example he had set.”

Join the conversation as a VIP Member