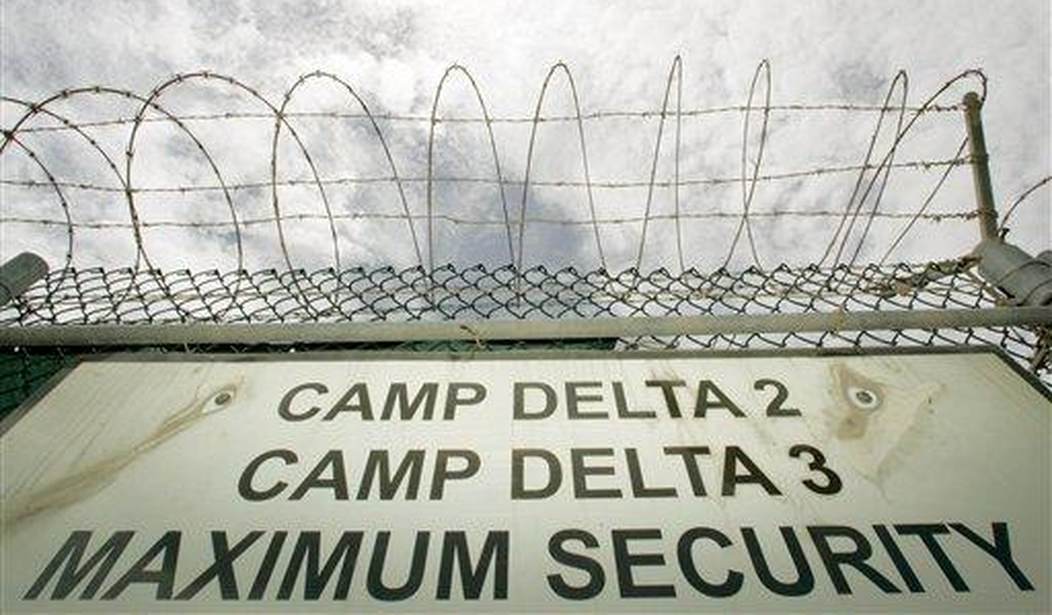

We've all heard that the law requires the administration to give Congress 30 days notice before releasing prisoners from the U.S. terrorist detention facility in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba -- a provision the White House willfully ignored in the recent release of five Taliban commandos in exchange for Army Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl.

But the law -- specifically the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2014 -- requires much more than that. Congress did not intend for the president to give lawmakers a simple heads-up. Instead, the House and Senate ordered that any such 30-day notification must include:

1) A detailed statement of the basis for the transfer or release.

2) An explanation of why the transfer or release is in the national security interests of the United States.

3) A description of any actions taken to mitigate the risks of re-engagement by the individual to be transferred or released ...

4) A copy of any (review board) findings relating to the individual.

5) A description of the evaluation (of conditions in the country to which the individual would be transferred).

Of course, the Obama administration did none of that in the Bergdahl/Taliban case. And the specificity of the law -- it is certainly not a casual requirement -- makes that decision more consequential.

In addition, it's safe to assume that Congress meant what it said -- the Defense Authorization Act passed by voice vote in the House and by a vote of 84 to 15 in the Senate. In passing the notification requirement, Congress was speaking with very nearly one voice.

After the Bergdahl affair, there's no doubt Republicans are steaming over Obama's decision to ignore Congress. But the president's longer-term problem may be with his own party.

Some Democrats are already unhappy. "It comes to us with some surprise and dismay that the transfers went ahead with no consultation, totally not following law," Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein, chairwoman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, said recently.

Recommended

Then, after a briefing in which the administration tried to sell lawmakers on the wisdom of the deal, other Democrats emerged with doubts undiminished. "That did not sell me at all," said Sen. Joe Manchin. "I still have concerns," said Sen. Mark Pryor. And Sen. Mark Begich -- like Pryor facing a tough re-election battle this year -- said some of his concerns had been allayed, but "there are still some questions."

Maybe Democrats will eventually fall in line. After all, in this case, the U.S. got something in return for freeing the five Taliban commanders. Democratic lawmakers can go to voters and make the case that even if Bergdahl deserted, he was still an American soldier and the United States had an obligation to get him back.

Certainly Bergdahl was the key to the White House argument in its "explanation" to Congress. "The administration determined that the notification requirement should be construed not to apply to this unique set of circumstances," National Security Council spokeswoman Caitlin Hayden wrote in a defense of the decision, "in which the transfer would secure the release of a captive U.S. soldier and the Secretary of Defense, acting on behalf of the President, has determined that providing notice as specified in the statute could endanger the soldier's life."

But what about Obama's next Guantanamo release? It's no secret the president wants to close the detention center. What if he wins nothing in return for giving more hardened terrorists their freedom?

There's no question how Republicans will react -- GOP Sen. Lindsey Graham is already threatening impeachment if there are more releases. But what about the president's party?

Having relied on the U.S. obligation to take care of its troops as an explanation for the Bergdahl case, Democrats might have a difficult time falling in line the next time if there's no American to be saved.

Back in December 2013, when Obama signed the Defense Authorization Act into law, he issued a now-famous signing statement in which he argued the notification clause "would violate constitutional separation of powers principles.

"The executive branch must have the flexibility, among other things, to act swiftly in conducting negotiations with foreign countries regarding the circumstances of detainee transfers," Obama wrote.

The message was clear: The president will act as he chooses, no matter what Congress wants. The next Guantanamo release could make the Bergdahl battle seem tame.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member