Amazon founder Jeff Bezos -- whom National Public Radio called in December "by far the wealthiest person on the planet" -- used a small sliver of his vast fortune in 2013 to buy The Washington Post.

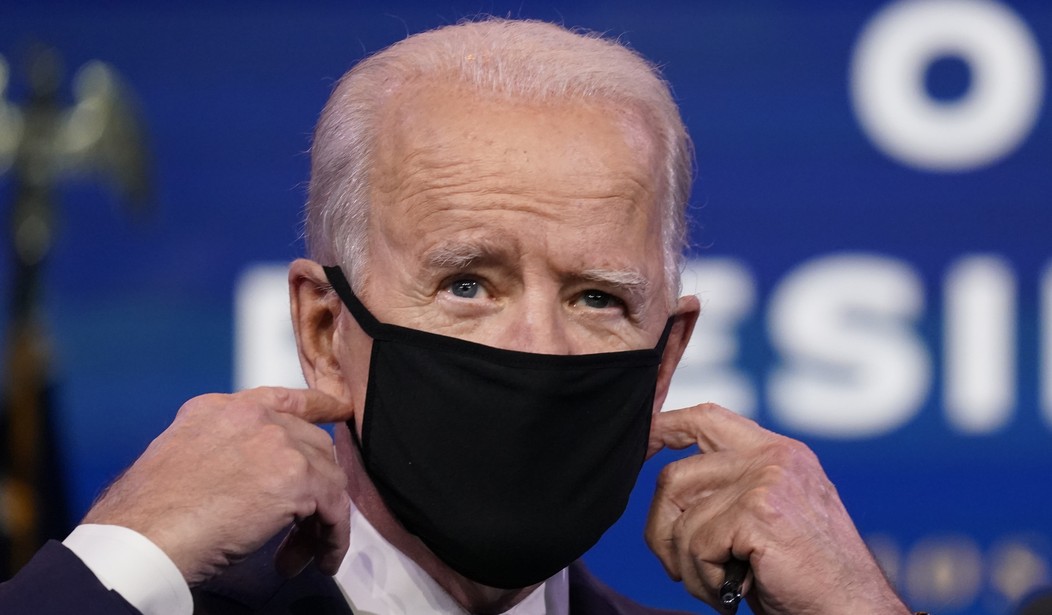

In 2020, this newspaper endorsed Joe Biden for president.

"Mr. Biden's competence and honor are more important in this cycle than any particular stand on any particular issue," the Bezos paper said in a Sept. 28 editorial.

Did it have a right to make this endorsement?

The First Amendment says: "Congress shall make no law ... abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press." Therefore, the answer is yes.

But under a constitutional amendment Biden is proposing, the question could become: How much, if anything, could the Bezos paper -- or any other organization -- spend on speech that is for or against a politician?

"In 1997, and many years afterward," says a page on Biden's campaign website, "he co-sponsored a constitutional amendment that would have limited contributions as well as corporate and private spending in elections and prevented the damage caused by the Supreme Court in Citizens United."

"Toward those ends, Biden will: Introduce a constitutional amendment to entirely eliminate private dollars from our federal elections," says the Biden website.

"Biden believes it is long past time to end the influence of private dollars in our federal elections," it says. "As president, Biden will fight for a constitutional amendment that will require candidates for federal office to solely fund their campaigns with public dollars, and prevent outside spending from distorting the election process. This amendment will do far more than just overturn Citizens United: it will return our democracy to the people and away from the corporate interests that seek to distort it."

Recommended

Biden's website links to the congressional webpage for Senate Joint Resolution 18 -- the constitutional amendment Biden co-sponsored back in 1997 (when it lost 38 to 61).

This failed amendment said in part: "Congress shall have power to set reasonable limits on the ... amount of expenditures that may be made by, in support of, or in opposition to, a candidate for nomination for election to, or for election to, Federal office."

Now, suppose this amendment had been ratified. Then, suppose Congress had enacted a law saying no individual or corporation could spend more than $1,000 on any given day supporting or opposing a candidate for federal office.

Under that restriction -- made constitutional by Biden's amendment -- would a newspaper be able to pay for the writing, layout, printing and distribution of an edition that endorsed (or opposed) Joe Biden for president"?

In the 1975 case of Buckley v. Valeo, the Supreme Court reviewed the Federal Election Campaign Act that limited "expenditures by individuals or groups 'relative to a clearly identified candidate' to $1,000 per candidate per election." The court explained why this kind of restriction was unconstitutional under the First Amendment.

"It is clear that a primary effect of these expenditure limitations is to restrict the quantity of campaign speech by individuals, groups, and candidates," the court said in a per curiam opinion. "The restrictions, while neutral as to the ideas expressed, limit political expression 'at the core of our electoral process and of the First Amendment freedoms.'"

The court went on to conclude that the law's "independent expenditure limitation is unconstitutional under the First Amendment."

Now, some might say that newspapers -- because they are press organizations -- have a right to speak about political candidates in a way other corporations do not. The First Amendment, after all, specifically protects freedom "of the press."

But, in the Citizens United case in 2010, the Supreme Court reviewed a federal law that prohibited "corporations and unions from using their general treasury funds to make independent expenditures for speech defined as an 'electioneering communication' or for speech expressly advocating the election or defeat of a candidate."

The law, as the court explained, defined an "electioneering communication" as "'any broadcast, cable, or satellite communication' that 'refers to a clearly identified candidate for Federal office' and is made within 30 days of a primary or 60 days of a general election."

The law exempted the media from this rule. But, then, the Supreme Court said the government could not treat the First Amendment rights of a corporation that operates a news outlet differently from one that does not.

"'We have consistently rejected the proposition that the institutional press has any constitutional privilege beyond that of other speakers,'" said the court.

"With the advent of the Internet and the decline of print and broadcast media, moreover, the line between the media and others who wish to comment on political and social issues becomes far more blurred," said the court.

"And the exemption results in a further, separate reason for finding this law invalid: Again by its own terms, the law exempts some corporations but covers others, even though both have the need or the motive to communicate their views," said the court. "The exemption applies to media corporations owned or controlled by corporations that have diverse and substantial investments and participate in endeavors other than news. So even assuming the most doubtful proposition that a news organization has a right to speak when others do not, the exemption would allow a conglomerate that owns both a media business and an unrelated business to influence or control the media in order to advance its overall business interest. At the same time, some other corporation, with an identical business interest but no media outlet in its ownership structure, would be forbidden to speak or inform the public about the same issue.

"This differential treatment cannot be squared with the First Amendment," said the court's opinion, written by Justice Anthony Kennedy.

In pursuit of his goal "to end the influence of private dollars in our federal elections," Joe Biden -- according to his campaign website -- would amend the Constitution to "overturn" this Supreme Court decision.

Then government could limit the money Americans spend on political speech.

Terence P. Jeffrey is the editor in chief of CNSnews.com.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member