The famous quote is “vox clamantis in deserto,” or “a voice crying in the wilderness.” The meaning is to arrive at truth, yet to be unheard. Today, we live in a period of great un-hearing. Truth is spoken, but few are listening. This is true in many areas, including human space exploration.

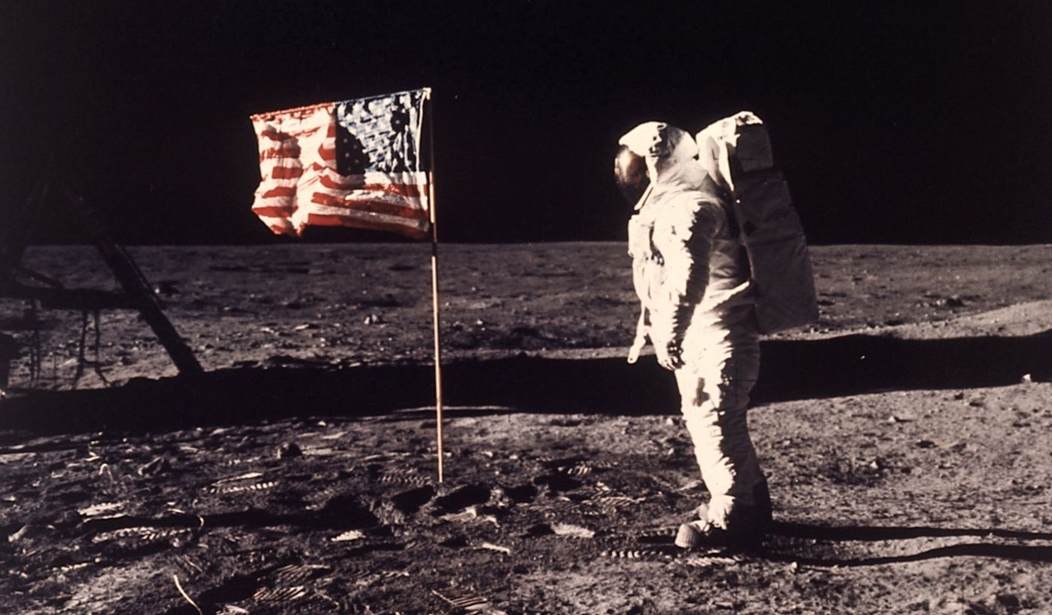

With the 51st anniversary of Apollo 11’s remarkable moon landing this past week, it’s important to remember that Buzz Aldrin – now 90 – is still a pathfinder – and our “voice in the wilderness” when it comes to pressing forward with human space exploration.

Aldrin still regularly thinks, writes, and speaks on the topic. His observations are worth hearing. Here are a few – and why they are worth knowing, or remembering, especially as we look back on a time of enterprise, risk-taking and enormous accomplishment for America.

First, as Aldrin has pointed out, exploring space is about human destiny. He is fond of saying, “we explore, or we expire.” There is an ultimate truth in his point. The human quest to know, reach outward, experience events firsthand, and explore the unknown is strong. The impulse is especially strong in America, founded by daring, undaunted pilgrims and pioneers.

While national security and science have animated recent ventures into space, it is the powerful force of human curiosity that – in the end – drives highest interest. We want to know what it feels like to walk on the moon, peer over the rim of a crater new to human eyes, look beyond the next boulder, and eventually land on and learn more about Mars. It is the doing, to satisfy the want to know – which pushes us.

Second, as Buzz and Apollo 11’s anniversary remind us, America is an exceptional land. We seem to be able to “go where no one has gone before,” physically, intellectually, and in ways that reflect our innate national comfort with daring.

Recommended

As Aldrin has written, “our national past offers us courage, confidence and a bearing on the future.” We are determined to keep pioneering, in our personal, professional, and national lives. We are right to be pioneering in space – and we are the leaders in having done so. Fifty-one years after walking on the moon, no other nation has yet repeated the feat.

Third, as America pushes forward with landing a man and woman on the moon, then sending humans to pioneer Mars – both exciting ventures – Buzz Aldrin reminds us to be as realistic as we are idealistic. Aldrin notes “space is a risky place.” As we explore, we must prepare for mid-course corrections. Gemini and Apollo both required that.

Perhaps most interestingly, Aldrin has made a pitch for rethinking two issues. He believes we should blend America’s exceptionalism in private enterprise and public policy, becoming comfortable with public-private partnerships – and also with international cooperation.

In effect, just as Aldrin pioneered orbital rendezvous mechanics, neutral buoyancy training for astronauts, efficacy of space tourism, and mathematical feasibility of orbiting cyclers to and from Mars, he is ahead of the curve again.

He believes that, by reference to ideas like President Eisenhower’s “Atoms for Peace,” an international effort to tame nuclear development, a public-private partnership of American companies and NASA should be melded into a larger international effort to press forward with international human space exploration.

As he recently noted, “Eisenhower advanced the idea that nuclear technology – what it promised and threatened – might be better managed with international cooperation,” an appeal that “grew the International Atomic Energy Agency and Treaty on Nuclear Non-Proliferation, making the world safer.”

Aldrin’s idea is that longer-range human space exploration is – far from a zero-sum-game mission – more a species-wide undertaking. His idea seems to be that, whatever competitive and security pressures drive near-Earth policy, a larger calling pulls the human species – as a species – into distant space.

As with Eisenhower, Aldrin sees value in early agreement among nations to manage human space exploration responsibly, collegially, and internationally – from Earth. Doing so might preserve peace in distant venues, at least on moon and Mars.

To get there, Aldrin sees a need for greater cooperation between governments and private exploring ventures – much as early risk-takers got government funding for oceanic exploration. Buzz Aldrin says this is the time “to configure a public-private international alliance tying together leading sovereign space agencies and top private sector space exploration companies.”

Last, but maybe first in time, Aldrin sees a need to constantly rethink plans for getting to the moon – assuring the way is efficient, not weighed down by unnecessary infrastructure, corporate welfare, or political deals that comprise efficiency, integrity or architecture of the enterprise.

Remarkable is the knack of this mentally nimble old moonwalker for calling it right, before others get there. He was right on orbital rendezvous, neutral buoyancy, space tourism, the math on cyclers, and public-private teaming. He may be right again. For now, just another nod to a great American – and a living, thinking pioneer.

Robert Bunn, former senior law enforcement attorney in FL and commentator on national issues, has special interests in rocketry, intelligence, international affairs, and national security. He holds multiple degrees from Harvard University and is author of two books, one of which is The Panama Canal Treaty: Its Illegality and Consequential Impacts.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member