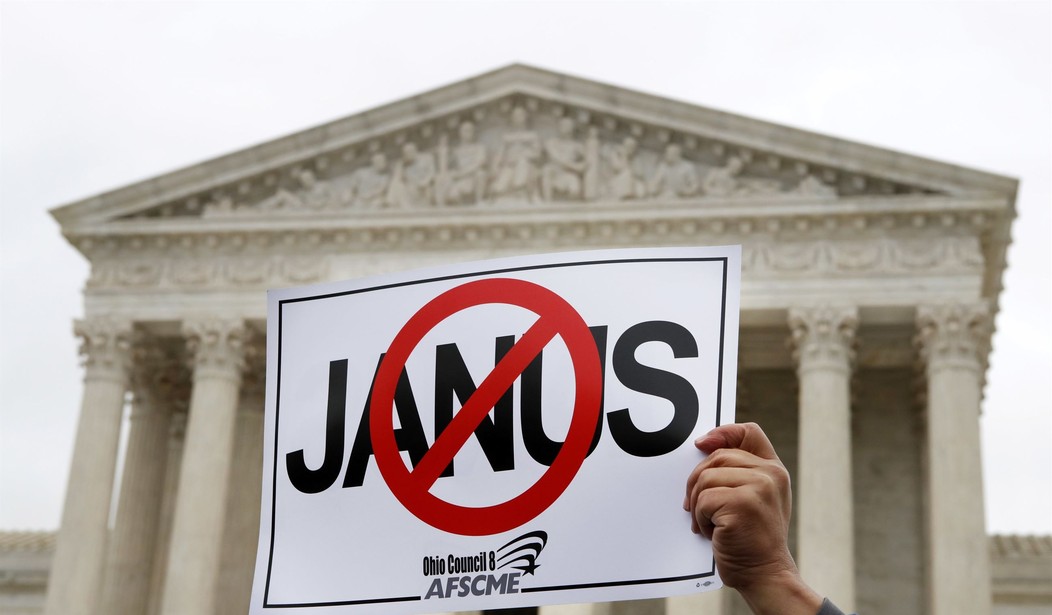

While the Supreme Court heard oral argument, last week, in Janus v. American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), the court of public opinion focused not so much on the constitutionality of the law in question, i.e. justice, but instead on the partisan impact of the decision, i.e. politics.

The case concerns Mark Janus, a child-care specialist for the Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services, who refuses to join the union. Nonetheless, by state law, Janus is forced to pay “agency fees” to AFSCME.

Those agency fees are 78 percent of what a union member pays in dues. The other 22 percent? The amount AFSME claims to spend on politics — with all contributions going to Democrats. Mr. Janus, represented by the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation and the Liberty Justice Center, argues that the union is intrinsically political and that he has a First Amendment right not to be coerced to pay AFSCME to keep his job.

Most observers believed the Supreme Court was poised to rule forced union dues unconstitutional in a different case, Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, before Justice Antonin Scalia’s passing in early 2016. Instead, without Scalia or a replacement, the Court deadlocked 4-4 in that case. Now with President Donald Trump’s pick, Justice Neil Gorsuch, replacing Scalia, most Court-watchers believe Mr. Janus will prevail, 5-4.

Maybe that is why a Washington Post editorial advances the notion that the court was presented “with two questions. The first is the legal issue . . .” and the second “implicit” question is “how the court should conduct judicial review in a deeply polarized society.”

The Post also claims that plaintiff Mark Janus and his legal team are seeking an “extraordinary remedy in the context of the Supreme Court’s tumultuous recent history.”

Recommended

But that history is not Mark Janus’s.

Or the union’s.

Or even U.S. labor relations’.

The history the editors are referring to is Washington’s bitter 2016 political fight over President Barack Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland to replace Justice Scalia. Republicans refused to hold hearings on the nomination or bring Mr. Garland to a vote. Unusual, but also lawful, as the Constitution requires that the U.S. Senate consent to the nominee.

What does political polarization have to do with the facts or law of this case? Nothing. Except . . . what’s in peril is a system whereby government workers who do not wish to join a union are nonetheless forced to pay union dues that somehow get directly funneled to only one of those political poles.

So, if the Court nixes current law, AFSCME might wind up with fewer dues paying members . . . meaning less money for AFSCME’s political pet, the Democratic Party.

And Democrats — now stuck with a conservative replacement for the late Justice Scalia — are left only with Obama’s pronouncement: “Elections have consequences.”

“[B]efore those justices pick up pens to sign organized labor’s death warrant,” pleads the Washington Post’s Dana Milbank, “perhaps they’ll pause to consider, as AFSCME attorney David Frederick warned at the end of arguments Monday, that they will ‘raise an untold specter of labor unrest throughout the country.’”

“Death warrant”? Sure, that’s hyperbole, but as fellow Post columnist Charles Lane offers, “A recent survey by AFSCME of its 1.6?million members found that only 35?percent of them would definitely pay dues if not required to do so.”

Which, again, doesn’t seem like a good argument for continuing to coerce working folks into coughing over the money.

“If stripping a political advocacy group of the power to force workers to join their efforts is a crippling event,” wrote David Harsanyi, a senior editor at The Federalist, “then it’s an event worth celebrating.”

Still, the capital’s paper of record will not be breaking out the champagne. Rather, embarrassingly, the Post makes its bizarre case for “steering the court modestly down the middle of the road.”

A lady, blindfolded, holding scales and a sword symbolizes justice. That blindfold is there not so judges can avoid reading the law. Instead, it represents the absolute imperative to be blind to the politics.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member