The question of which philosophies and sensibilities define the American conservative movement has become much murkier in recent years. Like a torn battle standard, the label has found itself snatched up by all sorts of right-wingers, anti-left-wingers and — confusingly — anti-anti-right-wingers. These factions subscribe to wildly different ideologies. In fact, they often diametrically oppose one another, obscuring the question further. Whatever commonalities they share stem from a mutual distaste for the woke left.

One ideological rash that has spread across this loose ideological confederation is an obsession with ends and an ambivalence for the means. Proper procedure and the oft-maligned cultural and moral norms have found themselves frequently trampled in pursuit of some sundry policy victory or — of greater import — “owning the libs.” This rash often festers into the bleeding sore of “Great Man” worship, a disease of the human condition that transcends time. It is the belief that if the political right could concentrate sufficient political power in a great singular leader (or Übermensch), he will lead We the People, to political and cultural victory.

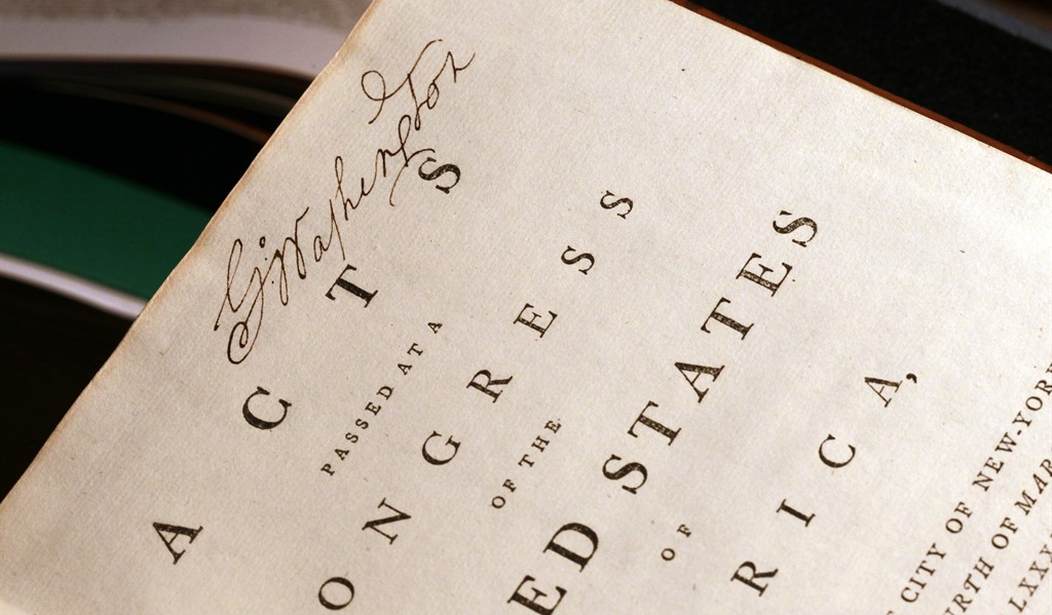

In the American context, however, hardly anything could be less politically conservative, in the sense that few ideas could be more at odds with America’s national political tradition. The Founders believed that the structure of government — the procedures by which governing is done — mattered. Besides being profoundly revolutionary, the political architecture they erected emphatically divided powers between branches of government — precisely to prevent any would-be Übermensch — or ascendent faction — from asserting its will unchecked.

The Constitution also took pains to protect minority rights from majoritarian tyrannies, adding further friction to the political process. The Founders (who did not live in 21st century, the freest time in human history) worried that government poses an ever-present threat to liberty. Far from becoming anarchists, however, they used political science to craft a system whose mechanism would tend to secure individual rights.

Recommended

The Founders, and later generations, dedicated countless volumes to explaining this political theory. James Madison’s Federalist No. 51 provides a brilliant rough outline. “In republican government, the legislative authority necessarily predominates,” Madison writes. This alone rebuffs the populist Übermensch theory. “Conservatives” who hope for a powerful executive already fundamentally misunderstand America’s political genius. The Constitution relegates the executive, no matter who occupies it, to a supporting role in domestic affairs. Indeed, to re-establish constitutional order, conservatives must return power stolen by, or delegated to, the executive branch and the administrative state to its rightful owner — Congress.

Madison wrote that preserving good governance requires “auxiliary precautions” beyond grounding political authority in the will of the people. Therefore, the Constitution divides power among the federal government’s branches (and even between the two houses of Congress). In Madison’s words, it gives to “each department the necessary constitutional means and personal motives to resist encroachments of the others.” Far from clearing the road for an enlightened leader to march in triumph, the Founders installed myriad speed bumps as precautions against tyranny. They expressly intended the relationship between branches to be somewhat adversarial — at times even messy. From this jostling, they believed consensus and good policy would likely grow.

The Constitution did not simply separate powers at the federal level. It divided authority between the central government and the state capitals. It entrusted broadly interstate and geopolitical matters to the federal authorities and the everyday tasks of governing to state and local officials. Federalist No. 39 clarifies that state authorities were to be “no more subject, within their respective spheres, to the general authority, than the general authority is subject to them, within its own sphere.” In Federalist No. 51, Madison argued that this division provides “a double security” to “to the rights of the people.” He continued: “The different governments will control each other, at the same time that each will be controlled by itself.” Even should the Übermensch accumulate unchecked federal power, the independent power of the states would check those ambitions.

The tenets of the Constitutions — legislative supremacy, checks and balances, separations of powers between and within levels of government, and a profound respect for natural rights — created and preserved a superlatively exceptional nation. Within the broad spectrum of the conservative sensibility, thinkers may debate many things. Disagreement and robust intra-movement debate make conservatism strong. However, anybody who repudiates these broad concepts and the institutions that embody them has excommunicated himself from the American conservative tradition.

David McGarry is a policy analyst at the Taxpayers Protection Alliance.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member