Michael Bloomberg’s “Nanny State Fever” is spreading like a bad virus across America. Texting bans have become a new and favored tool in local and state government arsenals, with which to control citizenry and raise revenue. At least 30 states now ban texting while driving. Claiming that, “something must be done,” cash-strapped local governments are taking advantage of anti-texting hysteria and authorizing sweeping new powers for law enforcement officers. Coincidentally, these laws quickly become an easy source of revenue.

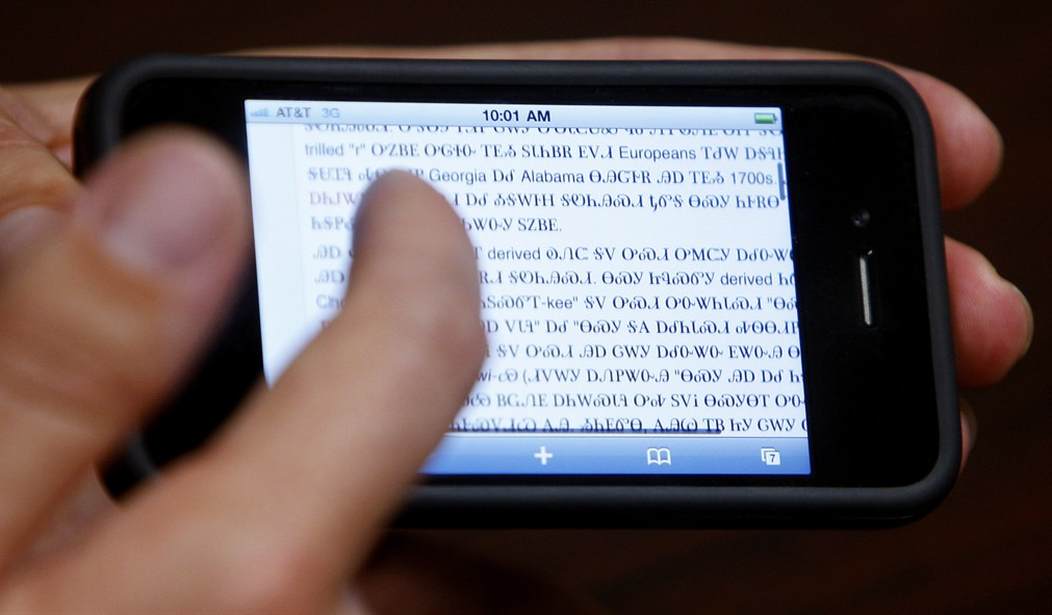

Many of these laws go far beyond a simple ban on texting, however. According to the text of an ordinance recently passed in Charleston, South Carolina, for example, the ban on cell phone use is not limited to texting, but applies to any use of a cell phone beyond talking -- web browsing, GPS directions, email and even scrolling through music. Simply looking at a phone while driving could earn drivers large fines plus court costs -- which often approach or even exceed the fines themselves.

Worse still, these tickets are virtually impossible to defend against. Issued at the discretion of the officer, a driver’s only defense often is his word against the word of police; after all, how do you prove you weren’t looking at a music playlists or GPS screen. It doesn’t take a Matlock to know who judges most often side with in such contests. Thus, these tickets often go uncontested; making it easy-money for local governments facing budget short falls.

City council members and law enforcement officials claim these texting bans are all about “public safety,” not raising revenue; therefore, citizens should trust that these new police powers will not be abused. Such assurances ring hollow as texting convictions mount, along with resulting revenues. One officer in Gwinnett County near Atlanta, Georgia, is responsible for roughly one-quarter of the entire state’s texting-ban convictions, writing more than 800 tickets already this year. At $150 a pop, and assuming most offenders pay the fine rather than risk losing a challenge in court, this single officer likely has generated more than $100,000 for the state – thanks to his “concern” for public safety.

Recommended

If these broad, revenue-generating, anti-texting powers follow the historical trends of other public safety measures such as red light and speeding cameras, the revenues generated quickly will become addictive. License plate scanners, initially instituted for “public safety,” increasingly now are used to automatically assess parking fines for illegally parked cars. Similarly, the Washington Times reports that the District of Columbia’s traffic enforcement camera program doubled its revenue from 2011 to 2012, bringing nearly $100 million in revenue from fines.

With such significant sums of money on the line, it comes as no surprise that government contractors and police officers are being pressured to squeeze ever more money out of taxpayers. American Traffic Solutions, a contractor hired by DC to operate its cameras, recently was accused of manipulating photos to make it harder for wrongly accused drivers to defend themselves in court.

Do these revenue-generating traffic schemes actually make roads safer for residents? The short answer is, No. Studies such as those conducted by the Highway Loss Data Institute, a non-profit dedicated to traffic education, show that texting bans have no impact on distracted driving, and may even contribute to an increase in car accidents. “Texting bans haven't reduced crashes at all,” Adrian Lund, president of both HLDI and the related Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, tells CNN. “In a perverse twist, crashes increased in three of the four states we studied after bans were enacted.”

Yet, local government officials continue to insist that such programs are enforced solely for the safety and benefit of citizens.

Nobody is denying that texting-while-driving -- or, any form of distracted driving -- is dangerous. However, police already have ample means with which to address unsafe driving; tools that do not create broad new government powers susceptible to abuse. By using “distracted driving” and “unsafe operation” ordinances already on the books, police can punish bad drivers without netting thousands of other drivers into a government-backed traffic trap. This approach also would protect the constitutional rights of drivers, by requiring a higher standard of proof of wrongdoing than merely a police officer’s “observation” of “illegal cell phone use.”

Join the conversation as a VIP Member