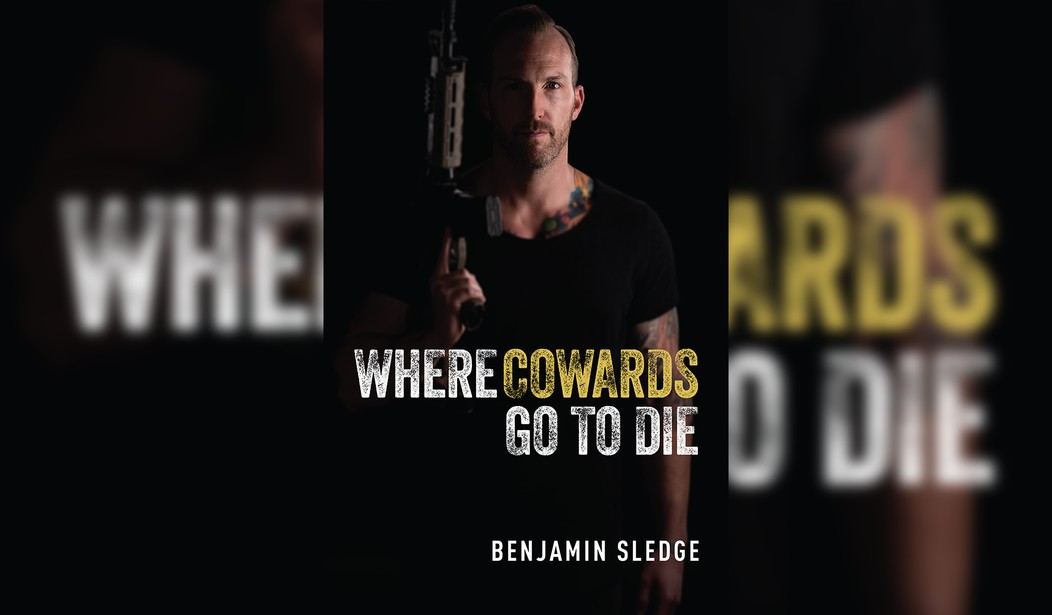

Editor's Note: This is an exclusive excerpt adapted from "Where Cowards Go to Die," by Benjamin Sledge, out July 5 (Regnery Publishing).

"I know you fought in both wars, Sledge. I've even seen the multiple medals hanging on the walls of your home, but aside from that, I know nothing about your time overseas. You never talk about it."

The coffee shop was slow and sleepy at six in the morning. Patrons with bleary eyes ordered espresso and breakfast tacos—an Austin, Texas, staple. While I'd already downed my first cup of joe, I was not awake enough to process the question, so instead I stared at my friend, Andrew.

Andrew and I—along with a few other men—met weekly to discuss spiritual matters and deepen our brotherhood and faith. I was the only veteran in the group, a fact I'm well aware of given that less than 1 percent of the population have served in the longest-running wars in the history of the United States. I am an anomaly. So when people discover that I not only served in the military but in multiple wars, their curiosity gets the better of them.

Andrew, though, was trying to understand. An architecture student at the University of Texas, he'd joined a group that encourages veterans to tell their stories. Civilians listen to the tales of combat, seeking to understand instead of judge, and this process gives veterans a therapeutic outlet. After Father Rocheford's suicide, I was trying to open up more but was still caught off-guard when Andrew tried this process with me.

Nursing my coffee to buy time, I finally spoke. "I used to. It was all I talked about for a while when I got home from Afghanistan. But that's also when I was struggling pretty badly."

Andrew's eye contact was intense. I could tell he wanted more.

"It's hard to talk about combat in a manner that doesn't offend people or make you sound crazy. Some stories are so insane, people will chalk them up to fiction, but that's how you know they're real. The more absurd they sound, the more certain you can be they happened."

Recommended

"How so?"

Explaining this concept was difficult. Frown lines formed over my forehead. "Sometimes I'll remember an event and think, nah, that didn't happen. It seems far too unrealistic, and I become convinced my brain made it up. Then I discover it's true when I get around guys from my old unit and we start telling war stories. I think some memories are too traumatic, though, and why we bury them until we get in those group settings. Still, it's like a phantom constantly lurks in your head. Certain sights, sounds, and smells beckon like old flames."

I paused, searching for a way to explain it to Andrew that he'd grasp. "It's like one of those moments when you're certain the girl at the supermarket is someone you dated, so you keep staring to see if she recognizes you. She doesn't, but as you walk to your car, you can't seem to shake the feeling. It's like we remain haunted by a ghost we're not sure existed."

Years later, an old romance movie and novel, "The Ghost and Mrs. Muir," would help me grasp this phenomenon. The story revolves around a young widow, Lucy Muir, who moves to the English countryside near the sea. Her life is marked by failed romances, and the cottage she moves into is haunted by the soul of a roguish but charming sea captain, Daniel Gregg. The two fall in love, but because he's a ghost, there's no chance of them being together.

One evening, hoping she'll leave and find true love, Captain Gregg suggests that their romance was all a dream. However, whenever Lucy looks at the sea, she feels a terrible longing. In life, she becomes more haunted than she ever was by Gregg's ghost. Perhaps that is the curse the combat veteran endures: the mercy of forgetfulness and the unexplained torment of the past.

What I really wanted to tell Andrew was that I loved war. I wanted to talk about it all the time. I loved combat with every fiber of my being. I relished in the fear, adrenaline, brotherhood, and utter thrill of knowing I might catch a bullet. The whole experience made life grand and exciting.

But I also hated war.

I hated it with a passion so intense I never wanted to see another conflict in my lifetime. I'd give anything to ensure my future children never had to endure what I'd seen. I hated the warmongering of politicians and the violence we readily embraced. I hated death. I hated myself for being an active participant in human suffering. War was, and is, evil. Anyone who says differently has never seen combat or has slipped into the black abyss of nihilism.

These paradoxical emotions left me conflicted, without a way for people to understand them. How can you love and hate war at the same time? Even worse, I knew that if another Pearl Harbor happened, I'd sign right back up. Even C. S. Lewis tried to enlist again at the beginning of World War II, despite the combat injuries he'd sustained and friends he'd lost during World War I.

As the years have passed, I've grown far more contemptuous of the reasons we go to war, except for ending human rights violations. The minute you cry havoc and let slip the dogs, there will be human suffering and collateral damage. Innocent men, women, and children will die. I suppose that's why I've always felt torn in two. I'm part pacifist, part combat-hungry warrior.

Most people will probably chalk up the haunting memories and conflicted emotions to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Part of what made my wife, Emily, assume my actions and emotions stemmed solely from PTSD was finding me sleepwalking in our apartment. According to her, I would always stare out the window in our living room like I was looking for something, then return to bed. Other times, I'd awake to find I was staring at myself in the mirror. Those instances always scared the hell out of me, as did the vivid nightmares. I'd have to stare at the repetitive motion of a ceiling fan when I woke to remind myself I was home, not fighting in the Middle East.

But here's the thing: my memories didn't feel like PTSD. They felt like getting punched in the soul.

When I dug into my work in mental health, I discovered PTSD is a psychological response to a traumatic stressor. This explained my aversion to fireworks; they often sounded like incoming 107mm rockets. A common approach to treating PTSD, however, is exposure therapy—that is, slow, incremental exposure to past triggers in order to desensitize you to the stimuli.

After struggling for years on the Fourth of July to the point that it shut me down, I used this method to desensitize myself to fireworks. As a child I loved the noise, lights, and experience of shooting roman candles into the sky (and at my brother). I hated that I could no longer enjoy something that gave me so much joy because it was now associated with trauma. So I began to expose myself to fireworks in increments I could handle until I could enjoy them once more and associate them with fun and not artillery.

What PTSD didn't explain, however, were the nights I would stare at the photo of the dead enemy combatant in the blue Toyota Hilux. It didn't explain why I couldn't recall the Bermel Massacre, even though I'd written about it in my journal. Nor did it explain why I laughed about morally reprehensible situations, why Father Rocheford's suicide and Kyle's death weighed so heavily, or why I felt intense shame over some of my actions. When Starnes got married and had children, he admitted that he, too, felt intense guilt and shame about some of the more violent things he had done.

"I told myself I was doing it to keep you and Wegner safe," he explained. "Now it just eats away at me."

What's wrong with us veterans? It's like we continue to walk around with these gangrenous soul wounds that have never healed. Then we remain quiet, all while rotting away from the inside. More troubling is the fact that, while overseas, most of us never felt bad for killing, wounding, or maiming because we didn't see the enemy as human. The military teaches this to you from day one by shooting at pop-up targets and singing cadences about killing.

Instead, human beings become "tangos" (targets), "MAMs" (military-aged males), or "hajis” (an Islamic term of endearment for someone who'd made the hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca, which we'd turned into a slur). To have to reconcile your humanity with the person you're fighting would cause you to hesitate, and hesitation gets you killed. That's why we never humanize those we fight. Instead, they're "krauts," "nips," "zips," "gooks," and "hajis."

Once you get home from war, though, you try to bury what happened underneath mundane life experiences. Compared to the intensity of combat, your job is mundane. Your marriage is mundane. Your friendships—while deep—don't compare to the level of absolute devotion you had to those you fought beside. You become a human punch clock who repeats menial tasks, and the people around you have their heads buried in a cell phone while pretending to experience connection.

It's bullshit compared to war. So you start to think about war—the thrill and camaraderie. It's an escape—nostalgic and familiar—until one day the penny drops and you remember who you were and what you did.

Posttraumatic stress is different than a soul wound. Instead, there's a term for it: moral injury.

Moral injury is a term coined by clinical psychologist Jonathan Shay. The term refers to the emotional and psychological damage soldiers incur when they do things that violate their sense of right and wrong. Shooting a woman or child. Killing another human. Watching a friend die. All the things we do in war and laugh about to stay sane.

That's why I never talked about war with my wife, friends, or those outside the military. The bruise went deep, and to touch it made me flinch. It could shut me down emotionally or cause me to head straight to a bottle just to get the images out. I wonder if that's why my granddad didn't talk about combat, either. I suppose that's why we said nothing to each other. We knew what we'd done and perhaps felt the same soul punch.

I suppose war does that. The bonding and bruising of souls, I mean. While my granddad and I never talked about war, we felt the distinct brotherhood. And perhaps that's the greatest gift and curse combat gives you—the camaraderie. To this day, I've never experienced a deeper sense of brotherhood than when I was at war. That's the beauty. The tragedy is that you go home and never talk to one another until someone dies. At the funeral, you sit around retelling war stories and promise to keep in touch, but you don't. For that day, though, you're whole once more, surrounded by the men who would gladly take a bullet for you. Then you return to the world where your boss lets everyone at the company catch the proverbial shrapnel to make an extra buck. Is it any wonder why we only talk to those we served with about war?

Purple Heart and Bronze Star veteran Benjamin Sledge reveals the brutal reality of war and the struggle veterans face when returning to civilian life in his new book "Where Cowards Go To Die," out July 5. Sledge is a wounded combat veteran with tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, serving most of his time under Special Operations (Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations Command). He is the recipient of the Bronze Star, Purple Heart, and two Army Commendation Medals for his actions overseas. Upon returning home from war, he began work in mental health and addiction recovery. A prolific communicator, Benjamin has authored several viral articles in addition to being the author of two books. His work ranges from fiction, self-help, and investigative journalism to Christianity and the military. He lives in Colorado Springs, Colorado, with his wife, daughter, and son.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member