In 1935 George Dangerfield published "The Strange Death of Liberal England, 1910-1914," a vivid account of how Britain's center-left Liberal Party, dominant for a century, collapsed amid conflicts it could not resolve.

The Liberal Party had appeared impregnable. Its cabinet in 1910 included Herbert Asquith (in the midst of the longest consecutive prime ministership since the Duke of Liverpool's and until Margaret Thatcher's), and the future wartime leaders David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill. But after 1910 the party never won an election again.

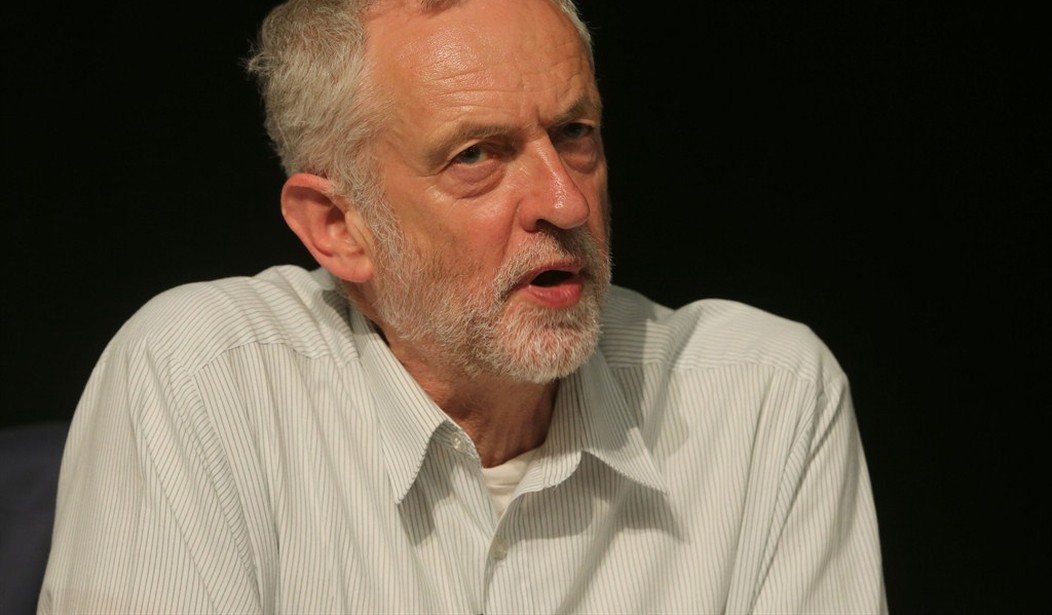

What got me thinking about Dangerfield's delightfully written book were political developments here and in Britain -- the monster crowds flocking to hear Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders on the West Coast and the likelihood that the far-left Jeremy Corbyn will be elected next month to head Britain's Labour Party.

The Sanders and Corbyn boomlets have things in common. Sanders has long styled himself a socialist and seeks income redistribution; Corbyn wants government ownership of railroads and coal mines. Both look with favor on 90 percent tax rates.

Both men are competing for leadership of parties with winning electoral records in the recent past. Democrats have won four of the last six presidential elections. Labour won large parliamentary majorities in 1997, 2001 and 2005.

But both candidates repudiate the architects of their parties' initial victories in the 1990s, Bill Clinton and Tony Blair. Sanders is not only running against the architect's spouse but against his record. Corbyn has suggested that Blair be tried for war crimes.

Recommended

Blair has responded in kind, charging that Corbyn's election would "annihilate" the Labour Party. Bill Clinton has not publicly commented on Sanders' campaign, and we can only speculate on what he thinks of Hillary Clinton's abandonment of his triangulation and third-way politics.

Democrats flirting with Sanders and comfortable with the current Clinton can argue that Barack Obama's two victories point to a different, farther-left majority than Bill Clinton's center-left governance. Hillary Clinton strategists say explicitly that they hope to duplicate her former boss's coalition rather than her husband's.

For Labour, the lurch leftward seems more clearly suicidal. Blair's successors as party leaders, Gordon Brown and Ed Miliband, moved left and lost. Miliband's attacks on Conservative "austerity" resulted in Conservatives gaining seats and, unexpectedly, a parliamentary majority. Corbyn would go still farther left.

How can we explain the rejection by American Democrats and British Labourites of center-left strategies that recently proved so successful?

One explanation is that people are acting out of principle. Left-wing Democrats and Labourites love to hear candidates echo those of their beliefs that are unpopular with the wider electorate. (Right-wing Republicans love this, too.)

Another is that today these parties have not been chastened by repeated defeats. Republicans held the White House for 16 of the 20 years before Bill Clinton won; Conservatives held Number 10 Downing Street for 18 years before Blair did. Partisans were willing to accept half a loaf in those circumstances.

A third explanation applies specifically to center-left parties, including Dangerfield's Liberals a century ago. They were bedeviled by demands from different constituencies -- Irish Catholics, feminist suffragettes, militant union leaders -- which their compromising tendencies could not assuage. Liberal Britain faced internal violence, Dangerfield argues persuasively, when it unexpectedly went to war in August 1914.

Parties that are uneasy coalitions of self-consciously divergent groups with varying agendas, groups that consider themselves out of line with (or oppressed by) the national majority, are prone to splinter. It's hard to keep everyone happy and onboard.

In May's election, the Labour Party lost Scottish seats to Scots Nationalists who won 56 of 59 seats; lost working-class votes to the anti-immigration UK Independence Party; and lost upwardly mobile Hindus and Sikhs to the lower-tax Conservatives.

Democrats face competing demands from teacher unions and poor parents; Black Lives Matter protesters and environmental cultists; and from skeptics about the Iran deal and pacifist-leaning doves.

What these constituencies have in common is an angry rejection of the center-left political formula that only recently produced impressive party victories. The first black president was able to corral 51 percent for re-election and retains enough loyalty

to keep most Democrats from grumbling about his performance.

But the leftward lunge so visible at Sanders rallies and Corbyn hustings pushes their parties to extreme positions and splinters what were majority coalitions. The strange death of the center-left threatens to make Britain solidly Conservative again and consign the Democratic Party to unanticipated minority status.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member