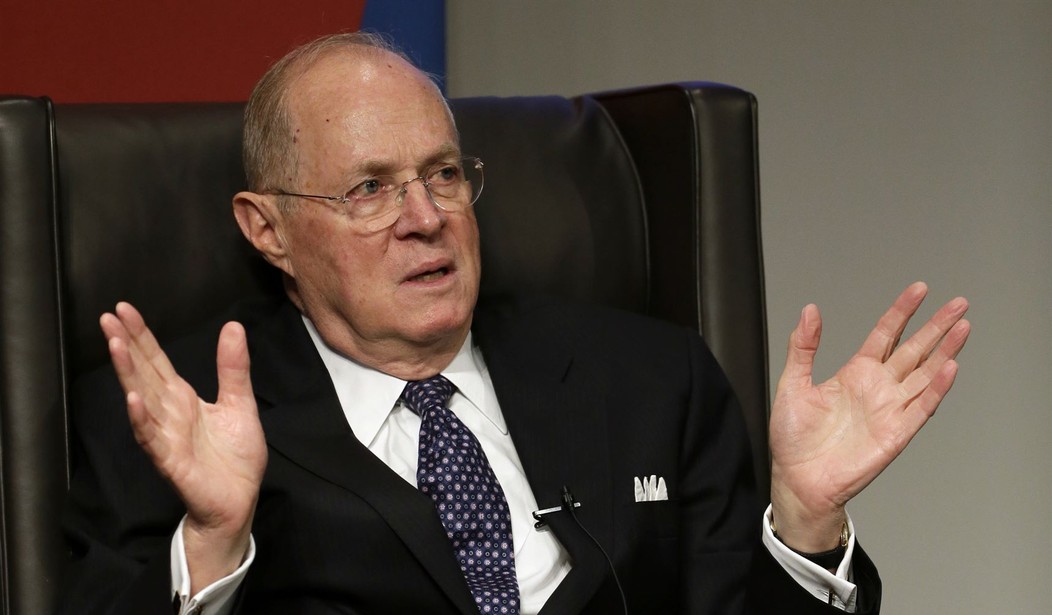

History will remember Justice Anthony Kennedy for advancing an illogical argument to deny a God-given right.

That places him on the opposite side of a fundamental question from the great Roman senator Cicero -- as well as from Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton and Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

In 1825, an 82-year-old Jefferson wrote a letter putting the Declaration of Independence in context.

He wanted people to know: There was nothing unique or new about the philosophy it embraced.

"Neither aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, nor yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the American mind," Jefferson said.

"All its authority rests then on the harmonizing sentiments of the day," he wrote, "whether expressed in conversation, in letters, printed essays, or in the elementary books of public right, as Aristotle, Cicero, Locke, Sidney, &c."

Cicero was murdered in 43 B.C. What might he have said that enlightened the Declaration of 1776?

"There is a true law, a right reason, conformable to nature, universal, unchangeable, eternal, whose commands urge us to duty, and whose prohibitions restrain us from evil," Cicero wrote in about 54 B.C.

"It is not one thing at Rome and another at Athens; one thing today and another tomorrow; but in all times and nations this universal law must forever reign, eternal and imperishable," Cicero said. "God himself is its author, its promulgator, its enforcer."

What did Hamilton think of this argument?

"The sacred rights of mankind are not to be rummaged for, among old parchments, or musty records," Hamilton wrote in 1775. "They are written, as with a sun beam, in the whole volume of human nature, by the hand of the divinity itself; and can never be erased or obscured by mortal power."

Recommended

That Jefferson, a hypocritical owner of slaves, understood that the inalterable God-given natural law prohibited slavery is demonstrated by some of the inscriptions now carved into his memorial in Washington, D.C.

They include these Jeffersonian words: "God who gave us life gave us liberty. Can the liberties of a nation be secure when we have removed a conviction that these liberties are the gift of God? Indeed, I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just, that His justice cannot sleep forever. Commerce between master and slave is despotism. Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate than that these people are to be free."

In 1963, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was unjustly jailed in Birmingham for protesting the immorality of segregation.

King, the president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, rightly offered no repentance for nonviolent resistance to unjust laws. In the true spirit of America, he explained why that resistance was necessary.

"A just law is a man-made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God," King wrote in his Letter from Birmingham Jail.

Speaking of those who engaged in nonviolent resistance against segregation, King declared: "One day the South will know that when these disinherited children of God sat down at lunch counters they were in reality standing up for the best in the American dream and the most sacred values in our Judeo-Christian heritage, and thusly, carrying our whole nation back to those great wells of democracy which were dug deep by the founding fathers in the formulation of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence."

In 1992, Justice Kennedy joined with Justices Sandra Day O'Connor and David Souter in writing the Supreme Court's opinion in Planned Parenthood v. Casey.

Kennedy defended what he called "the right of the woman to choose to have an abortion before viability and to obtain it without undue interference from the state."

He argued that this "right" was protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

"It declares," Kennedy said, "that no state shall 'deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.' The controlling word in the cases before us is 'liberty.'"

If the right to kill an unborn child, as Kennedy argued, is protected by the "liberty" recognized in the Fourteenth Amendment, what is the ultimate source of that "liberty"?

Is, as Cicero said, "God himself ... its author"? Are men, as Jefferson wrote, "endowed by their Creator" with it? Is it, as Hamilton declared, written "by the hand of the divinity itself"? Does it, as King would ask, square "with the moral law or the law of God"?

No.

In Kennedy's opinion, the "rights" that constitute "liberty" are something each person -- or Supreme Court justice -- can make up for themselves.

"At the heart of liberty is the right to define one's own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life," Kennedy wrote. "Beliefs about these matters could not define the attributes of personhood were they formed under compulsion of the State."

However, though Kennedy gave to each person the authority to determine what "liberty" is, he nonetheless limited a women's liberty to kill her unborn child to only that time which precedes the child's "viability."

Viability, of course, is a mutable thing -- subject to advances in machinery and drugs.

But then, in Justice Kennedy's world, all rights are mutable -- subject to whomever holds five votes on the Supreme Court.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member