Imagine a time when liberals dominate the late night talk show circuit, American society is ripped apart by politics and issues, and a Republican hated by the media launches a campaign for president.

And then the Republican enjoys help from some of the most famous entertainers in the land.

In his autobiography, For Laughing Out Loud, Ed McMahon described himself in 1968 as a “great admirer” of Hubert H. Humphrey. Today, younger generations may know Humphrey as the namesake of a huge, drafty, and retired covered stadium. In the 1960s, however, Humphrey played the role filled by Henry Wallace before him and George McGovern after. He represented the far Left of the Democratic Party.

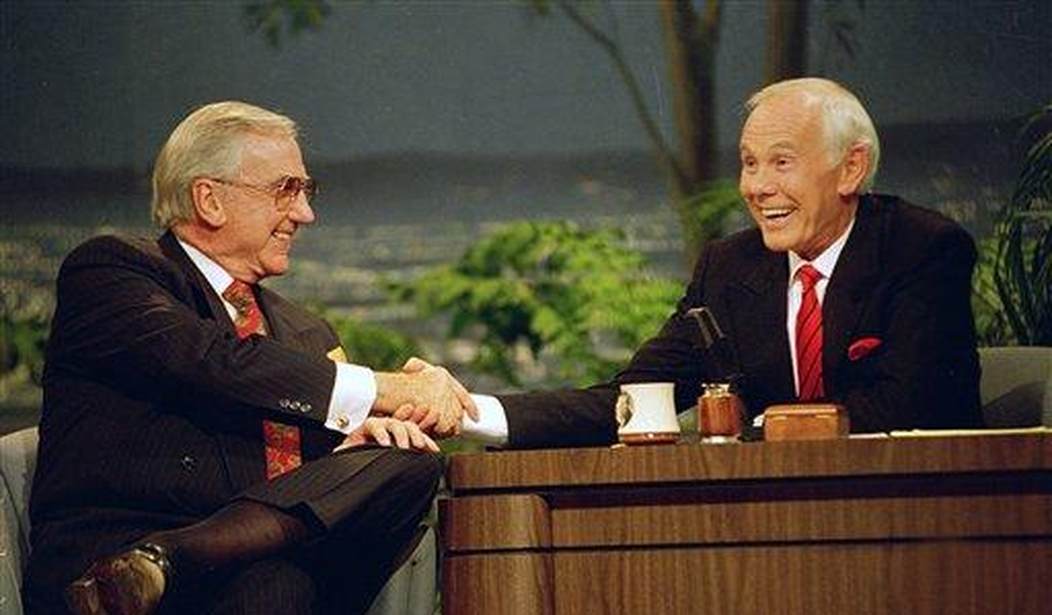

Johnny Carson leaned to the political left himself, despite having treasured friendships with figures such as Ronald Reagan. He and his legendary sidekick McMahon understood that their success depended on entertaining all Americans, or at least as many as possible. Politics then and now tended to slice into an entertainer’s popularity. They used their comedic carving knives to great effect on both sides, never alienating over politics or policy.

Even handedness meant inviting political figures on their show and giving them a chance to shine.

Before he announced his candidacy for president in 1968, Richard Nixon was a guest on The Tonight Show. Since the 1950s, the media had enjoyed an adversarial relationship with the occasionally caustic, but still popular, former congressman.

Conscious of the political impression left by his infamous 1960 debate appearance, Nixon invited McMahon to his Fifth Avenue office and asked his advice on how to succeed in television.

John F. Kennedy had used the same show while Jack Paar was hosting to boost his chances in 1960. Nixon needed the same effect eight years later.

Recommended

Contrast that to today. Imagine a controversial Republican asking a celebrity liberal for advice. And then consider the celebrity liberal giving him helpful tips.

As McMahon remembered in the late 1990s, “today, media consultants are paid thousands of dollars to answer that question.” He offered advice, such as “the most important thing to do on television is to include everybody” and that includes viewers at home.

“Find common emotions” and reaffirm connections with the audience as well as the host.

The last bit of advice was personal. McMahon discussed how the working man audience related to him as one of the working men of the show. “The last thing I told him,” McMahon wrote, "was that when he walked out from behind the curtain, he should shake hands with me.” He added “When Barry Goldwater was on the show, he didn’t bother to shake my hand. Now Barry Goldwater is a nice man, and he certainly didn’t mean to slight me, but people noticed and they didn’t like it.”

The political journalist Theodore White remembered that in 1960, Nixon seemed “banal, his common utterances all too frequently a mixture of pathetic self-pity and petulant distemper.” Those who knew the man elected president in 1968 and again in 1972 assured him that behind the aggressive persona lay “the real Nixon,” a man White later found to have a “voracious, almost insatiable curiosity of mind,” and was also “a jovial, relaxed anecdotist.”

Nixon’s appearance showed warmth, humor, and self-deprecation. When asked if he was running in 1968, Nixon encouraged Carson to try. “You’re young . . . you come over on television like gangbusters. And boy, I’m an expert on how important that is."

Carson asked “you’re not gonna lend me your makeup man are you?” Nixon replied quickly, “No, I’m going to lend him to Lyndon Johnson.”

And then he hired the makeup staff from The Tonight Show for his presidential run.

Ed McMahon enjoyed the honor of an invitation to organize and direct the inaugural ball. “I agreed to do it,” he remembered, “I mean, this was a request from the president-elect of the United States – and I put together a wonderful show.”

The social divisions were no tougher in 1968 than today. In fact, the divisions between ideologies, people of different backgrounds, and generations were far deeper and broader in those days than today.

But the entertainment industry in many cases tried to rise above and beyond it.

At its peak under Johnny Carson, The Tonight Show could regularly pull in nearly 20 million viewers in a nation with a population of around 200 million in 1970. Since then, the nation’s population has nearly doubled and the same program pulls in approximately less than 2 million viewers per night.

Carson and McMahon achieved something virtually unknown in today’s media climate: complete objectivity. Political jokes were spread evenly and never hit too hard below the belt. They gave all equal treatment, and even extended advice and help as a courtesy. Audiences of all beliefs trusted in the respect these performers had for them.

And that is the quality that is missing today: respect. Even President Reagan and House Speaker Tip O’ Neill would take a break from political barbs to hit the links together. Reagan even performed during a 1986 roast of O’ Neill, where the two sons of Ireland traded good natured insults about their roles in American politics.

For over a generation, the entertainment and news media have grown bitterly partisan. The same vitriol aimed at the rhetorically feisty Donald Trump is not too far beyond that directed at the laid back and gentlemanly George W. Bush or Mitt Romney. In that same time, their industries, not the GOP, have lost respect and credibility. Trump’s treatment of them reflects a decision to not take insults and half-truths lying down, as he feels his Republican predecessors have.

Returning to respect and civility means going back in time and learning what made men like Carson, or Cronkite, for that matter, more successful and trusted than their modern counterparts.

And that starts with basic respect.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member