Editor's note: This piece is excerpted from Hate Crime Hoax: How the Left is Selling a Fake Race War by Dr. Wilfred Reilly.

Chapter 7

Throwing Fuel on the Fire: Media Complicity with Hate Crime Hoaxes

One of the most remarkable things about the symbiotic relationship between the mainstream media and hate crime hoaxers is how long a particular pattern of reporting has been going on. When I first began my research, I half expected hate hoaxes to be a phenomenon unique to the social media era, the result of activists realizing that few things could get more likes than a YouTube video of a popular campus radical with a perfectly blacked eye ranting against racism. Not so. Laird Wilcox’s Crying Wolf, published in the mid-1990s, contains nearly as many cases of note as the data set I collected over a similar length of time. In fact, it would appear that the rate of hate crime hoaxes has been fairly consistent for at least the past twenty to twenty-five years. For that entire time and longer, mainstream media coverage of hoax incidents has followed the same template.

The general pattern of media coverage of fake or questionable hate crimes is (1) get wind of a sensationalist allegation of a hate attack; (2) dramatically report it, often on the front page or during prime time; (3) ignore growing evidence that the allegation is a hoax; (4) finally receive indisputable proof that the allegation is a hoax; and (5) run a retraction of the original front-page story on page twenty-six of the Leisure and Pet Cats section. This template accurately describes the coverage of Yasmin Seweid’s false claim that Trump supporters attacked her for wearing a hijab—but also the reporting on the infamous rape accusations against the Duke lacrosse team in 2006 and the 1992 claims of Azalea Cooley that “Burn N*gger Burn” had been painted on her house along with a swastika. Though this has been going on for at least three decades, it has apparently never occurred to many reporters and media executives to be suspicious of wildly unlikely hate crime allegations.

Recommended

To the extent that a single beginning point for this phenomenon can be pinned down, it all started with Tawana Brawley.

The First and Still the Biggest: The Tawana Brawley White Gang Rape Hoax

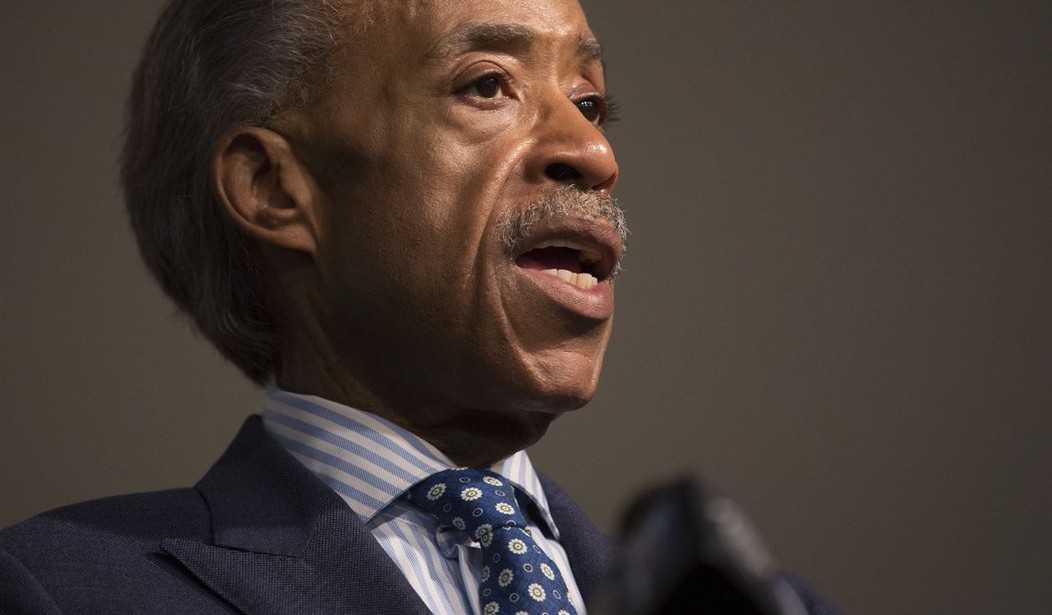

Probably the most famous hoax hate crime of all time, which made Al Sharpton into a national figure and demonstrated the shocking level of media credulity given to openly absurd hate crime claims, was the Tawana Brawley case. This sleazy case spawned the famous slogan, “Tawana Told the Truth!” But she didn’t.

The Brawley case began on November 28, 1987, when a fifteen-year-old African American student—who had been missing for four days from her home in suburban Wappingers Falls, New York—was found “unconscious and unresponsive” lying in a trash bag a few feet from a New York City apartment where she had once lived. The young woman seemed to have been brutally attacked. Her body was smeared with what appeared to be stinking human feces, and her clothing had been burned and torn. After Brawley had been taken to a local emergency room, it was discovered that the words “KKK,” “N*gger,” and “b*tch” had been written all over her body in charcoal. During a subsequent interview with the police—Brawley would only communicate with a Black officer, and only via “gestures and writing”— she claimed that she had been taken to a wooded area and raped repeatedly by three white males, one of whom she described as a police officer, apparently in uniform.

Unsurprisingly, Brawley’s allegations caused an international firestorm. The Wikipedia account of the case describes it as having captured almost every “headline across the country” during portions of 1988. Multiple major rallies were held to denounce the attack and demand justice for its “victim.” Actor Bill Cosby, years before he himself would be accused of sexual assault by more than two dozen women, helped organize a legal fund for Brawley that raised a substantial amount of money. At least some of this cash wound up paying the legal fees of flamboyant and race-baiting lawyers Alton Maddox and C. Vernon Mason, who rapidly began handling Brawley’s public relations alongside civil rights activist Al Sharpton.

It is fair to say that Sharpton, Maddox, and Mason took the Brawley matter to a level of spotlight-seeking rarely seen in American jurisprudence, before or since. On separate occasions, members of the trio claimed that the New York state government was trying to protect potential defendants in the Brawley case, none of whom would ever be found “because they were white,” and accused the assistant district attorney Steven Pagones of being one of Brawley’s rapists. Black Muslim minister Louis Farrakhan also became involved with Brawley’s cause around this time, leading a march of more than a thousand activists through a working-class New York neighborhood in support of Tawana.

While all of this entertaining libel and rioting was going on, Brawley’s actual legal case was falling apart. A sexual assault kit administered the night of Brawley’s admission to the hospital came back negative, turning up no DNA or other evidence of sexual assault “anywhere on (Brawley’s) body.” More broadly, the young woman had shown no sign of exposure to the elements or to inclement weather, something even the New York Times drily noted would be quite unusual for a victim “held for several days in the woods at a time when the temperature dropped below freezing.”

As a result of all this, the grand jury refused to indict any of the accused. On October 6, 1988, they went further and took the highly unusual step of issuing a 170-page legal report noting that Brawley was probably lying. According to the grand jury, there was essentially no medical possibility that Brawley had been “abducted, assaulted, raped, (or) sodomized.” They explicitly condemned the “unsworn public allegations against Dutchess County ADA Steven Pagones.” Among several other findings, the grand jury report pointed out that the epithets on Brawley’s body had all been written upside down—a strong indication that she had written them herself—and that the feces on her body had been traced by forensic experts to a neighbor’s large dog. The grand jury also pointed to a probable motive for Brawley’s lies. Like Yasmin Seweid almost two decades later, she apparently wanted to avoid discipline at home. Brawley seems to have spent at least the first night of her four-day disappearance with a boyfriend, and she feared violence from a strict step-father who disapproved of her spending nights with young men.

The fallout from the collapse of Brawley’s case was significant, though it notably did not include the mainstream media’s examining its own role in promoting a transparently absurd hate crime narrative for more than a year. Consider what I just said. Brawley accused a uniformed police officer and the assistant district attorney of taking her to the wilderness and raping her for days . . . and became a cause célèbre. If these claims could be believed, are there literally any allegations that could not be?

Even after her story was exposed as a fake, the activist Left essentially refused to believe that Brawley had lied. Generally speaking, even those liberal thinkers who conceded that her actual story was false argued that something similar must actually have happened. In any case, no one should doubt the Continuing Oppression Narrative that her original accusations had played into. Well-known legal scholar Patricia Williams opined that Brawley “obviously was the victim of some unspeakable crime.” Issues of racial and gender violence remained to be dealt with “no matter how she got there. No matter who did it to her—and even if she did it to herself.” It would be hard to come up with a better short summary of the “ctrl-left” worldview. If a Black woman falsely accuses a group of white men of rape, she must have done so because she was a victim of racism, and whites as a group need to figure out how best to apologize to her.

In contrast, most normal tax-paying citizens of all races were outraged and disgusted by the behavior of Brawley and her legal team. On May 21, 1990, Alton Maddox actually had his license to practice law indefinitely suspended by the state’s supreme court following a disciplinary hearing “regarding his conduct in the Brawley case.” District Attorney Steven Pagones, for his part, demonstrated

why it is generally a bad idea to accuse a government prosecutor of being a rapist and a pedophile; he sued Sharpton, Mason, and Maddox for defamation and won a $345,000 judgment after a series of lengthy procedural delays. Cynical readers may be amused to know that Sharpton’s $65,000 obligation to Pagones was not taken care of until 2001—when supporters such as Johnnie Cochran paid it, in order to retire a long-standing embarrassment to the “civil rights icon.”

That brings us, two decades after her allegations, back to Tawana Brawley. Pagones also successfully sued Brawley, who apparently did not bother to show up in court and contest his charges. He was awarded a judgment of $187,000 against her, but the New York Post noted in 2012 that she had never paid him a dollar. It would appear that at least one judge read the article; roughly one month after the piece appeared, Brawley’s wages were ordered garnished, forcing her to at least get started on paying Pagones—although it is unlikely she will ever be able to pay him the entire sum owed.

Some lost income aside, Brawley seems to have escaped any serious fallout from the false allegations that made her globally famous. According to a well-received documentary about her case, The Tawana Brawley Story, she works as a nurse in Virginia, has a relatively happy and stable life, and recently converted to Islam. A Daily News feature on the twentieth anniversary of her case mentions that she and her parents still contend that the attack on her actually happened. In fact, they recently “asked the New York State Attorney General . . . and Governor . . . to reopen the case,” so that Brawley can finally receive the justice she deserves.

What a marvelous idea. Let us hope that someday she gets exactly that.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member