In his article “Unraveling the Mindset of Victimhood,” the American psychologist Scott Barry Kaufman recommended taking the following short test to determine whether you have a “victimhood mindset”:

“Rate how much you agree with each of these items on a scale of 1 (“not me at all”) to 5 (“this is so me”):

- It is important to me that people who hurt me acknowledge that an injustice has been done to me.

- I think I am much more conscientious and moral in my relations with other people compared to their treatment of me.

- When people who are close to me feel hurt by my actions, it is very important for me to clarify that justice is on my side.

- It is very hard for me to stop thinking about the injustice others have done to me.”

If you scored high (4 or 5) on all of these items, you may have what psychologists have identified as a “tendency for interpersonal victimhood.”

I would add the following statement: “I define myself first and foremost as a member of a distinct social group (preferably a minority) that has been discriminated against all over the world and for centuries or millennia.”

The Israeli psychologist Rahav Gabay defines this tendency for interpersonal victimhood as “an ongoing feeling that the self is a victim, which is generalized across many kinds of relationships. As a result, victimization becomes a central part of the individual’s identity.” Those who have a perpetual victimhood mindset tend to have an “external locus of control”; they believe that one’s life is entirely under the control of forces outside one’s self, such as fate, luck or the mercy of other people.

Recommended

External locus of control means: I don’t see myself as the shaper of my own destiny, I always blame external forces. I blame society, discrimination, capitalism, etc. for defeats and setbacks. If other people are successful, I envy their success and put it down to “luck” or “social injustice.”

This attitude renders people powerless and helpless. Radical movements that cultivate this victim myth and promise that only an overthrow of society will change their personal situation then provide supposed strength.

The stories of successful people with disabilities that I tell in my book Unbreakable Spirit show that it is not external circumstances, but above all one’s own inner attitude, the “mindset,” that has a decisive influence on a person’s life:

As the book shows, Ludwig van Beethoven applied his incredible willpower to far exceed his own ambitions and overcome his supposedly limited physical possibilities and composed some of his greatest symphonies when he was already deaf. As Beethoven said: “Strength is the morality of the man who stands out from the rest, and it is mine.” Frida Kahlo, who was struck by polio as a child and then further physically disabled in a serious traffic accident, still became the most famous painter in Latin America. The world-renowned physicist Stephen Hawking explored black holes and explained the universe to us, despite being confined to a wheelchair and communicating via a speech computer.

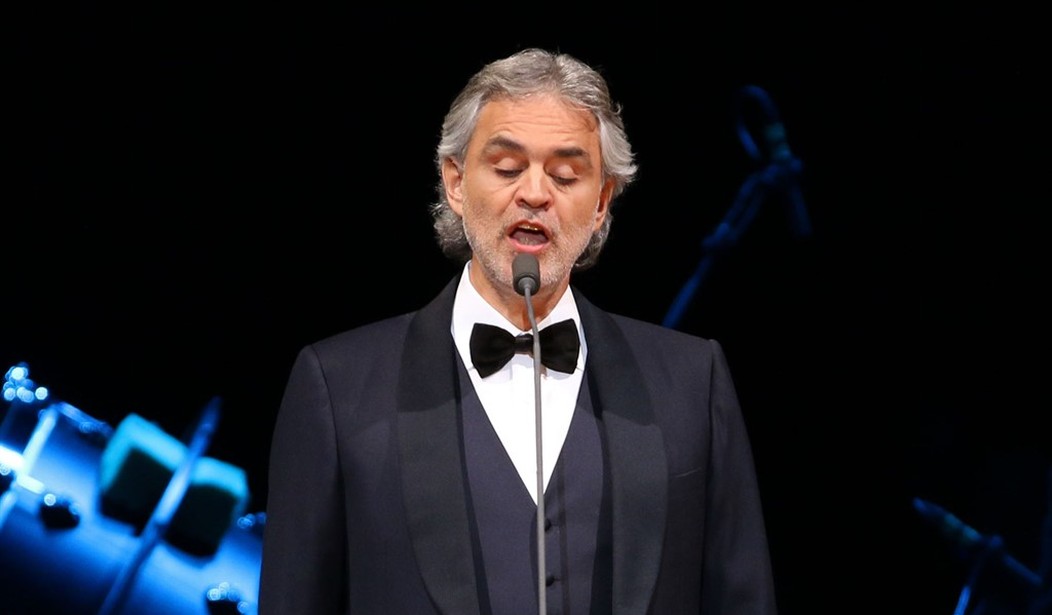

Ray Charles, Stevie Wonder and Andrea Bocelli became superstars of the music scene because they refused to accept their blindness as a disadvantage, and even succeeded in turning it into an advantage. Michael J. Fox had already achieved Hollywood celebrity when he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. That would normally mean the end of an actor’s career – but the Back to the Future star proved otherwise. In his early 20s, Felix Klieser had already become one of the world’s leading horn players, even without what is actually an indispensable prerequisite for playing the horn – arms.

Thomas Quasthoff is a thalidomide survivor and was born with severe malformations of his arms and legs – he became one of the greatest living tenors. Nick Vujicic, who was born without any arms or legs, is a highly sought-after motivational speaker and has inspired millions of people in 63 countries and met 16 heads of state around the world. “I believe,” Vujicic says, “if you create the life you want in your imagination, it is possible to create it in reality minute by minute, hour by hour, and day by day.”

A powerful desire to overcome the limits set by body or mind is what drives each of these incredible people. And the blind mountaineer Erik Weihenmayer conquered the Seven Summits, the seven most formidable peaks on the seven continents – including Mount Everest. The mental strength of people like Weihenmayer was that they never saw themselves as victims or members of a “disadvantaged” minority, but as strong people who were in control of their own destiny.

Rainer Zitelmann is the author of the book “Unbreakable Spirit. Rising Above All Odds”

Join the conversation as a VIP Member