of Buenos Aires.

Not the greedy streets

jostling with crowds and traffic,

but the neighborhood streets

where nothing is happening,

Advertisement

almost invisible by force of habit,

rendered eternal in the dim light of sunset,

and the ones even farther out,

empty of comforting trees,

where austere little houses scarcely venture,

overwhelmed by deathless distances,

losing themselves in the deep expanse

of sky and plains.

--Jorge Luis Borges

"The Streets"

Some places are empty not because what was there is gone, but because nothing was ever there. Other places present legendary ruins that never fail to move us. Still others have been replaced by cities of the same name but changed to such extent that what gave them character is gone, never to be retrieved except in memory and imagination. And then there are the places that never took shape outside some developer's failed plans and ambition.

Such a place is the Villages of San Luis, a grand dream of suburban living outside of Little Rock -- just off I-40 at Exit 42 where it meets Arkansas 365. Only the flamenco names of the already crumbling streets and curbs now speak of the dream that was as they wind past the few little houses left adrift as hope retreated into bankruptcy. The streets have grandiose names, but the modest houses here are anything but.

You can almost hear the guitars and stamping feet in the background as you read the names of the roads that never lived up to them: the boulevards Salinas de Hidalgo and San Luis. Olé! But all is quiet here. There are not even any ghosts, for this place has no past. And an uncertain future. By now the dream has gone through Chapter 7 bankruptcy and, like Detroit, is in Chapter 9.

Recommended

Advertisement

The largely empty development is covered with a poignancy as thick as the dust. There is nothing to be heard but the quiet. In a field far down the road, cattle are lowing. The straggly lots stretch into the deep expanse of Borges' deathless distances. Such a place cannot be said to have died. For it never lived.

Other places live only in remembrance and literature. For their successors bear no real resemblance to the cities that once occupied their locales and cast their spell there. Think of Cosmopolitan Alexandria, which by now has become the standard term for that period of its history somewhere between the construction of the Suez Canal and the rise of Gamal Abdel Nasser and the Arab Street. How could such a fabled city last? Permanence could not be expected of the city of Cavafy and E.M. Forster, a place that existed in literature more than life. On the first page of the first volume of Lawrence Durrell's four-part love song to that Alexandria, the city is recalled to life:

"At night when the wind roars and the child sleeps quietly in its wooden cot by the echoing chimney-piece I light a lamp and limp about, thinking of my friends -- of Justine and Nessim, or Melissa and Balthazar. I return link by link along the iron chains of memory to the city which we inhabited so briefly together: the city which used us as its flora -- precipitated in us conflicts which were hers and which we mistook for our own: beloved Alexandria! ... what is this city of ours? What is resumed in the word Alexandria? Five races, five languages, a dozen creeds: five fleets turning their greasy reflections behind the harbor bar...."

Advertisement

Not that the face of the beloved is that of some perfectly coiffed beauty: "Streets that run back from the docks with their tattered rotten supercargo of houses, breathing into each others' mouths, keeling over. Shuttered balconies swarming with rats. ... I wish I could imitate the self-confidence with which Justine threaded her way through these streets toward the café where I waited for her ... and smiling at her I inhaled the warm summer perfume of her dress and skin--a perfume which was called, I don't know why, Jamais de la vie." Never in this life.

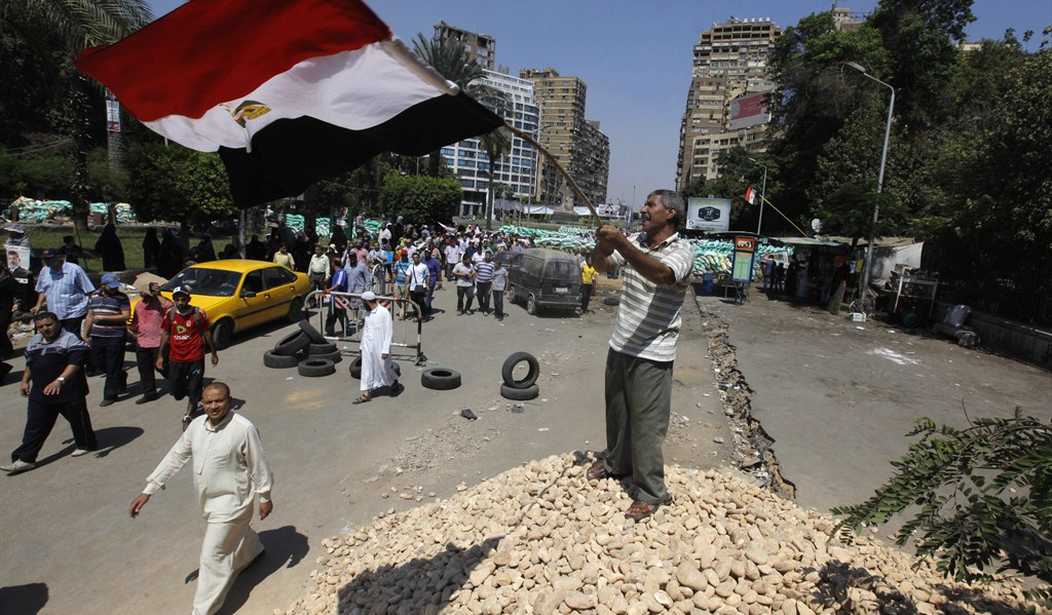

One can imagine, but would prefer not to, what Alexandria has become in today's anarchic Egypt -- just another prize contested by the fanatics of the Muslim Brotherhood, the ever present generals, and that rarest of phenomena in the Egyptian cauldron: idealistic young liberals. Only the sordidness remains the same.

Lucette Lagnado, an Egyptian-born reporter for the Wall Street Journal, and one more of that country's many exiles, referred to Lawrence Durrell's magnum opus just the other day:

"I have found myself wondering what Durrell would have said about Egypt today, where the tolerant, inclusive society he depicted has been almost utterly obliterated. In his time, beauties of every nationality -- French, Greek, Italian, Armenian, Egyptian-Jewish and Egyptian-Muslim -- would preen in their bathing suits along 'the sand beaches of Sidi Bishr,' as he calls one popular seafront enclave. These days, the foreigners and Jews are gone, and women who venture to the public beaches must go into the water covered from head to toe. Could Durrell ever have envisioned such a dark destiny for his city--for all of Egypt? 'Jamais de la vie,' I can hear him reply."

Advertisement

Durrell's cosmopolitan Alexandria is gone with pre-Katrina New Orleans, or pre-yuppie Austin, or old San Antone. They all live only in memory now. Perhaps that is why empty places that never were offer a kind of comfort. They are nonplaces, to adapt a term of Walker Percy's, and are spared the pain of memory as they recede into sky and plain.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member