This recent storyline on the typically cartoonish primetime drama "Scandal" was perhaps its most realistic -- even mundane. This is the air many young people breathe. Writing about the idea of temperance in a new book of essays, "The Seven Deadly Virtues," Andrew Stiles, himself a millennial, describes routine conversations as "often just an endless discourse on the question: 'How drunk was I last night?'"

This Snapchat-like snapshot of America in 2014 underscores how deeply complicated the work of renewing, rebuilding, repairing and replenishing family life is today.

Jonathan Last, editor of the "Virtues" essay collection, argues that these are "the seven cardinal modern virtues": freedom, convenience, progress, equality, authenticity, health and nonjudgmentalism. The problem with having these as our organizing framework is that they are largely superficial, concerned with "the outer self ... the part of ourselves that the world sees most readily," Last writes. They certainly are "insufficient" in fostering the moral supports a democracy needs.

For the fictional first daughter on "Scandal," her escape from the Secret Service was a desperate girl's declaration of independence, echoing a familiar staple of our times: the "good girl gone wild" that does no daughter any favors. In fact, judging by "the received wisdom, chastity is the thick-ankled stepsister of virtues," Matt Labash writes on his assigned virtue, with a flair for humor. "With an identical beginning and ending, along with the same number of syllables, chastity has the phonetic ring of the sexier virtue, charity. Except when you practice charity, you get pats on the back and deductions on your taxes. Being chaste just gets you odd looks and suspected of being a weirdo."

Recommended

The TV character's drug-addled transaction with two boys that night was taped by one of them, because that's the way we are now. Instead of encountering one another and creation, we click a photo or record the scene. "We increasingly live amid the ether of 'the cloud' and the pixelation of the screen, forgetting that our greatest tools for communicating with each other as human beings are not our sleek smartphones and laptop computers, but our less-than-perfect faces, gestures and voices, even when we are at our most annoying," Christine Rosen writes in promoting fellowship. "It is only when we are face-to-face and physically present with one another that we can experience the kind of genuine fellowship that has been the hallmark of civilization."

Where, of course, do we traditionally learn how to love one another "at our most annoying"? In the family, of course. And today's family is not helped by the modern "virtues" rewriting, undervaluing and poisoning the wellsprings of human flourishing: life itself, marriage, the uniqueness of man and woman.

Talk of the family so often today gets wrapped up in debates about these contentious issues. But work is also an essential element of the family. Pope Francis often talks about unemployment being an evil we face today, even saying recently that there is no family without work -- speaking to both the hard work of family life and the practical and even spiritual need for work in the life of a family.

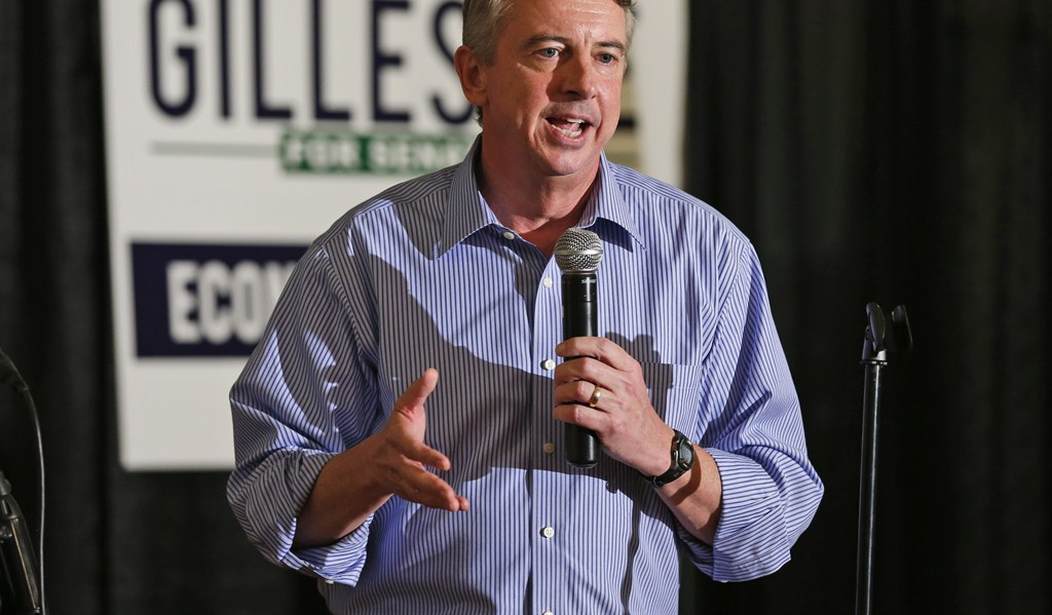

In Virginia, Republican Senate candidate Ed Gillespie has worked to promote a conversation about the dignity of work in his campaign stops and speeches.

"I don't think we make the case strongly enough from a conservative perspective that true social justice is enabling people to have the dignity of work, to be able to provide for themselves and their families, and that our policies make that possible," Gillespie told me in a recent visit to his Lorton, Virginia, campaign office. Economic polices need to help, among others, "a single mother who is facing the challenges of being a sole provider and a single parent," he said. "And that's particularly important if you believe in fostering a culture that respects and protects innocent human life," he said.

Work is never the sexiest of topics, but it is essential to our lives, and the life of the family. It's a scandal when we don't insist that it be taken more seriously.

Gillespie worries, among other things, that we may be losing our work ethic, and expressed gratitude for his parents' example of hard work.

Last writes of gratitude in his book: "It is gratitude that allows us to appreciate what is good, to discern what should be defended and cultivated." Facing a culture of changed values, what's old can be key to our renewal.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member