It was 1918, and for America, the war had been going on since April 6th the year before. By the time it was over, some 2 million Americans would have served in some capacity, and by common counting, 116, 516 men died. Incredibly, fewer men died from combat—53,402 than disease—63,114.

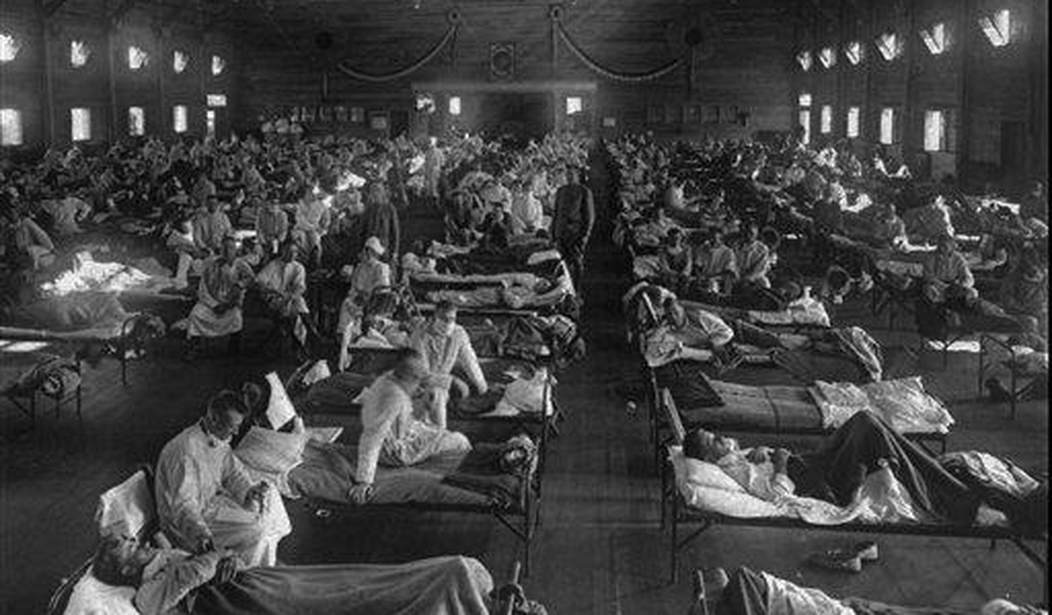

Another war began in March of that year, against an enemy we’d never fought before. Most historians agree that when an Army private reported sick one morning in Ft. Riley, Kansas, the battle was on, only no one knew it. More and more soldiers became ill. It was thought to be contained there by the end of April, by which time over a thousand soldiers were affected and 46 had died. Later, “it” became known as the Spanish Flu.

Highly contagious, the influenza showed up in a number of army camps, but no one was quick to understand its implications. There was no treatment for the flu, and notions of mitigation and containment were little understood.

By late summer, according to one source, the flu had mutated, and a second, deadlier wave struck Boston, where 4,000 people died in short order.

Pennsylvania, where I live, became one of the hardest hit states. Of the 675,000 Americans who died of the Spanish Flu, 60,000 were Pennsylvanians. In Philadelphia alone, nearly 20,000 people died within six months because the warnings of public health officials were ignored. Out of patriotic duty, civic leaders organized a fundraising parade in support of the war effort for late September 1918. By that time the spread of the flu, its contagion and its ravages had become well known. In fact, 600 sailors at the Philadelphia Navy Yard had come down with it, according to University of Pennsylvania Archives, which prompted the warnings from health experts. Some 200,000 people attended the parade, and within 72 hours, the first 12,000 were dead.

Recommended

By October, the second wave hit Western Pennsylvania, and while records are sparse, the city of New Castle may have been typical. Between October 1918 and January 1919, some 2,800 cases developed in the city, and 212 people died. On October 4th, a “Flu Ban” was ordered, which meant that, “all schools, churches, theaters, saloons, wholesale liquor stores, billiard rooms, dancehalls, fraternal lodges, and other public meeting places were closed until further notice.” Furthermore, “sick persons were ordered quarantined in a separate room in each afflicted house.”

The New Castle experience of a hundred years ago sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

Thirty days after the “Flu Ban” went into effect, there were over a thousand cases in New Castle, but it was thought the outbreak was under control. On November 10th, the ban was lifted, a move which turned out to be a deadly mistake.

The next day, November 11th, 1918, the Armistice was announced, and people celebrated in all the usual ways, as if there’d never been a flu epidemic. After a hiatus of only a week, more flu cases surfaced. Just before Thanksgiving, the number had reached 1,956. This pattern, no doubt, was reenacted in countless cities across the country.

A new “Flu Ban” was announced in New Castle, with even tighter controls amongst the populace. Street car operators were ordered to limit the number of passengers, and most importantly, to regularly clean the car interiors. The public was admonished about the “dangers of kissing,” amongst other things, and interestingly, “to keep their fingers out of their mouths when in public.” Quarantine signs were posted on houses where flu victims lived.

The second ban was lifted in mid-December, and still more influenza cases appeared, but to a far lesser degree. By early 1919, it was all but over. Lawrence County Memoirs included a rhyme that children made up for it:

I had a little bird, it’s name was Enza

I opened a window, and In-Flu-Enza.

Great takeaways from this century-old pandemic are that two weeks of a lockdown may not be enough and that sun and fresh air may be a most effective therapeutic.

In 1918, because there weren’t enough traditional hospitals, many patients had to be tented outdoors, and because they received far more fresh air and sunshine than in closed up, airless hospital rooms, doctors found, “If one report is correct, it reduced deaths among hospital patients from 40 per cent to about 13 per cent.” Whether that might be true today invites discovery.

There is little reason to believe that the world wide death toll from COVID-19 will reach the level experienced during the Pandemic of 1918—some 60 million people—but any number is too high, isn’t it?

Now Americans will do what we always do best: overcome any personal sacrifice, help one another, and face whatever is our enemy—inconvenient and difficult though it may be. Today, at our house, in our eighth day of self-quarantine, we are catching up on all that we’ve missed when out and about leading our usual, hectic lives. We can all do this!

Join the conversation as a VIP Member