In a recent article, in celebration of Black History Month, I revisited a black American whose shattering of PC icons has gotten him all but flushed down the memory hole of history.

That man is George S. Schuyler (1895-1977).

In addition to being a superb and prolific writer, Schuyler was a daring and genuinely free thinker. Unlike most of his contemporaries and ours, Schuyler refused to acquiesce in the fashions of the times.

Schuyler was unabashedly, passionately opposed to communism, and for the methods and national leaders of the Civil Rights movement he was contemptuous.

Take as but two notable examples Schuyler’s thoughts on Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X.

In “Dr. King: Nonviolence Always Ends Violently,” written in the wake of King’s murder, Schuyler remarks that the innumerable “mass demonstrations” that King spearheaded throughout his career—demonstrations that were initially designed to “advance a good cause”—have resulted “in clashes with police, looting, vandalism and killing rather than the goodwill and understanding originally intended.”

Schuyler admits to sharing King’s ends. It is the means that King appropriated to which Schuyler vehemently rejects. “From Dr. King’s original effort [the Montgomery bus boycott]…he contributed very little to the solution of the touchy problems of race relations in the United States.”

Schuyler’s identification of the problem is to the point: “If these problems are to be solved, it must be in moderation and through innumerable compromises rather than by use of abrasive tactics that produce irritation and ill will rather than understanding and cooperation.”

Recommended

In an especially cutting stroke of the pen that is sure to enrage the believers in “White Privilege,” Schuyler writes: “Wherever the Negro lives in the United States, he prospers only to the extent that he has the goodwill, tolerance, and acceptance of his white neighbors and fellow-workers.” This “process” is “necessarily…slow” and, thus, “cannot be speeded by razzle-dazzle tactics [of the sort that Schuyler attributes to King] which arouse suspicion and lend support to the propaganda of Negrophobes.”

Schuyler specifies what he takes to be several of King’s missteps in places like Alabama, Chicago, and Florida. He also takes King to task for linking his agenda—an ostensibly “civil rights” agenda—to the so-called “peace movement” that arose in response to the Vietnam War. “In short, as Dr. King’s influence waxed, his judgment seems to have waned.”

The larger King grew, the more reckless he became. “No more was said about praying en masse for white folks [,] but there was much talk about civil disobedience and defiance of the powers-that-be.”

After drawing readers’ attention to the tremendous progress that blacks at the time were making, Schuyler concludes his epitaph on King’s life with a warning: “It will not speed the process [of progress] to continue tactics of harassment and annoyance, but may cause a retrogression in race relations to the disadvantage of all.”

King “never learned this,” Schuyler tells us. But his “followers had better.”

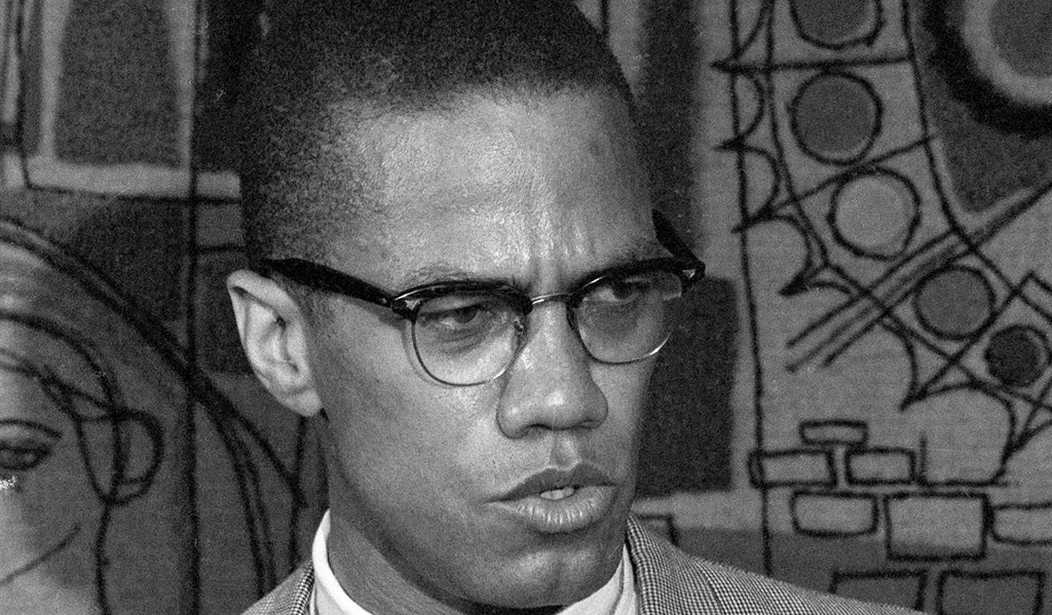

For all of his criticisms of King, Schuyler nevertheless commended him for what he thought was King’s sincerity of belief, genuine commitment to a worthy cause, and his talent of being “adroit.” However, for Malcolm X, another figure to emerge (eventually) from the 1960s as a Civil Rights giant, Schuyler had nothing but contempt.

Schuyler once debated Malcolm (along with James Baldwin and some others). Looking back on the event in 1973, eight years after Malcolm’s murder, Schuyler confesses to having been “initially astonished” by Malcolm’s “wide ignorance.” During that debate, Schuyler informed Malcolm—who was a spokesperson for the Nation of Islam, at the time—that there existed throughout the world many white Muslims and that Muslims were enslaving Africans for centuries before Europeans stepped foot on the continent.

Appearing genuinely unaware of these facts, Malcolm had no reply. Nor did it matter, for Malcolm, “like his father, a Baptist preacher who had been a follower of the late Marcus Garvey,” suffered from what Schuyler calls, “the all-Black complex [.]”

At the point at which Schuyler was penning his remarks on Malcolm X, the movement to eulogize him “as a great Negro leader” was afoot. It would be “better to memorialize Benedict Arnold,” Schuyler insists. “Malcolm was a bold, outspoken, ignorant man of no occupation after he gave up pimping, gambling, and dope-selling to follow Mr. Muhammad [the leader of the Nation of Islam who would eventually orchestrate Malcolm’s murder].”

Schuyler continues: “Like most of the loud-mouthed black leaders, he had but a tiny following…and all equally ignorant, if not more so,” than Malcolm himself.

Schuyler laments that over “the past generation,” “the black ‘leaders’ afflicting the nation have been mediocrities, criminals, plotters, and poseurs like Malcolm X.”

The common revisionist narrative today is that Malcolm X left the Nation of Islam after he had a change of heart and realized the wrongness of its anti-white ideology. Yet Schuyler saw then what in fact happened.

Muhammad ordered his ministers to refrain from uttering a syllable to the media in the wake of John F. Kennedy’s assassination. Malcolm, though, couldn’t resist characterizing this as a case of “the chickens coming home to roost.” In response, Muhammad terminated his premiere minister. Malcolm retaliated by spreading the word that Muhammad had been fathering children out of wedlock and, from that moment on, became a hunted man.

Desperately in need to remain relevant, Malcolm embarked on an eleven day trip that included a pilgrimage to Mecca. Upon returning, he claimed to have achieved a kind of racial enlightenment while abroad: He now recognized what Schuyler had schooled him about years earlier—that not only were whites people too, they could even be Muslims!

“It was good to know that Malcolm” learned “after that one little trip,” Schulyer asserts, “that…whites were human beings.” However, he “did not learn in eleven days that slavery was widespread in Arabia; nor about the slave traffic from Africa to Mecca where ‘pilgrims’ are still sold for payment of their passage to the Holy City.”

Schuyler adds that neither did Malcolm mention on his return home to the States “that he had visited radical and black racist groups in Africa, some of them Peace Corps workers.”

And Malcolm’s Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) continued to espouse “the same old racist bilge” in its newsletters.

Schuyler was having none of it: “It is not hard to imagine the ultimate fate of a society in which a pixilated criminal like Malcolm X is almost universally praised [.]” It is a society that has sown the seeds of its own destruction.

Let us revisit the work of George S. Schuyler this Black History Month—and every month.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member