“Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God.” (Matthew 5:9)

On May 25, 2020, George Floyd would become the victim of a horrifying homicide that has now been seen the world over. The brutality of Derek Chauvin, Thomas Lane, J. A. Kueng and Tou Thao is revolting to any person with a semblance of conscience left in their soul. This was an act devoid of all humanity and unrecognizable in its cruelty as an action worthy of a law-enforcement officer.

The pursuit of justice for George Floyd is not only justified but also necessary, lest our society succumb to the destructive notion that might makes right and that human life, already so devalued in America, would become so trivial a matter that homicide in broad daylight is just another thing we simply have to get used to. This is therefore not only an issue for the black community but one that assails the conscience of humanity. Justice must therefore be pursued.

But how to achieve justice is a mandatory requisite to keep before us. For not only the end but also the means to that end must be held firmly in the path of light, lest we contribute to the darkness that is currently gripping our nation. Difficult though it may be, departing from a righteous pursuit of the end—justice—will only stain the result.

Those who “hunger and thirst for righteousness” must ensure that the means do not bring about greater evils than we seek to repair.

Distinctions need to be made about the events that now grip our nation. It is a false equivalency to equate the seekers of justice with the looting, rioting and violence taking place across the country. For those with their head still in the sand, who refuse to understand a valid claim by the black community and the tens of thousands of Americans seeking justice, this easy out is inconceivably myopic. It is also increasingly difficult to identify who is who. Therefore, all should consider their further actions with the greatest of care.

Recommended

It is accordingly ever more important to affirm and clarify that the pursuit of justice can never be achieved through illicit means. One must also dispel the notion that other police officers, who also have families and are equally appalled by what took place, cannot see or feel the protestors’ pain. Is it really possible that in our pursuit of justice we should participate in the abuse of those who are also our brothers and sisters, just because they seem to be on the other side of the conflict? Is it rational to destroy people’s livelihood, loot, violently attack innocent bystanders, or deface city property on our way to justice?

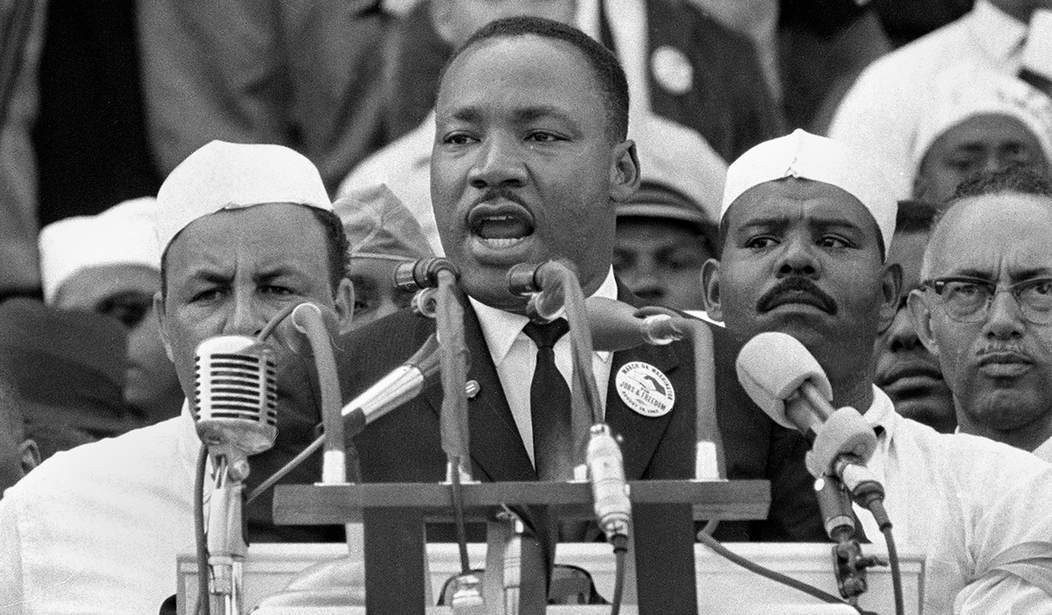

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s teaching about his own “pilgrimage to nonviolence” should echo in our souls and be etched in our minds as we move forward. He wrote about his own struggle with injustice and the danger he faced: “I had come perilously close to resenting all white people.” This holds true regarding white people, but also police officers, government officials and our neighbors, regardless of race. Avoiding resentment holds as a maxim that measures all, black or white. Injustice has more to do with the lack of a moral compass than the color of our skin.

As Dr. King taught us, “Constructive ends can never give absolute moral justification to destructive means, because in the final analysis the end is preexistent in the mean.” He would come to see clearly that peaceful means of resistance are not nonresistance to evil but rather nonviolent resistance to evil and the “only morally and practically sound method open” to achieve justice and be pursued in civil society. He understood that nonviolent resistance “was one of the most powerful weapons available to oppressed people in their quest for social justice.”

In his book Stride Toward Freedom, Dr. King recalled how his reflection on injustice drove him back to the Sermon on the Mount, and that is where all sides should now march to. Recalling the fruits of his “pilgrimage to nonviolence”—which seem most needed at this dire hour—he concluded “… that nonviolent resistance is not a method for cowards… This is ultimately the way of the strong man.” Violence disempowers the cause of justice. He remarked that, although passive physically in the sense of not doing violence, his mind and emotions were fully engaged seeking to persuade his opponent that he is wrong.

According to Dr. King, nonviolent resistance “… does not seek to defeat or humiliate the opponent, but to win his friendship and understanding.” The nonviolent resistance seeks to awaken a sense of “moral shame in the opponent.” The nonviolent measures are “directed against forces of evil rather than persons who happen to do evil.” Crucially, he wrote, “If he is opposing racial injustice, the nonviolent resister has the vision to see that the basic tension is not between races.” He would explain in Montgomery that the tension was ultimately not “between white people and black people” but “…between justice and injustice, between the forces of light and the forces of darkness… We are out to defeat injustice and not white persons who may be unjust.”

This difficult path would require, according to Dr. King, “a willingness to accept suffering without retaliation.” The logic of faith here was critical: “…the realization of unearned suffering is redemptive… Suffering is infinitely more powerful than the law of the jungle…” This was necessary to convert the opponent and open “… his ears which are otherwise shut to the voice of reason.”

Dr. King also taught that mind and spirit must be engaged in the struggle for justice and that that the nonviolent resister “avoids not only external physical violence but also violence of spirit.” That is, love could overcome, and yielding to hatred of the opponent would only “…intensify the existence of hate… Along the way of life, someone must have sense enough and morality enough to cut off the chain of hate.” Without breaking this chain, the evil of racial tensions will never end. Love alone could break that hatred—a chain that enslaves all of its subjects.

He meant love in the profound sense of that word: agape—a love beyond simple self-interest and human calculation. Not that the oppressed would love their “oppressors in an affectionate sense” but rather that the oppressed would understand the meaning of

“redemptive goodwill.” Agape, the highest form of love, he argued, “is love seeking to preserve and create community.”

His elevated notion of agape reached its highest expression in the Crucifixion: “The cross is the external expression of the length to which God will go in order to restore a broken community. The resurrection is a symbol of God’s triumph over all the forces that seek to block community.” To respond to injustice with hate would “…intensify the cleavage in broken community. I can only close the gap in broken community by meeting hate with love.”

Dr. King also recognized the wider cause and hope for this higher plane of love: Nonviolent resistance “is based on the conviction that the universe is on the side of justice.” This faith that God, or a higher force for others, worked to bring reality into a “harmonious whole” was critical to the possibility of hope for a better future.

We must be aware, as we go forward, that indeed the stronger side of fortitude is endurance and peaceful perseverance in justice, not attack and violence as the means to conquer evil. Dr. King’s reflection calls for all of those agitating, inciting and fanning the flames that will lead to greater violence to cease and desist. Words matter greatly at this time, and the irresponsible threats and constant inciting will lead us all to great peril. We must resist these dark forces from all sides and seek the higher path of the One who once taught: “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God.”

Join the conversation as a VIP Member