Has America reached the point where, once Washington has expanded a program, not even the new spending's most vociferous critics dare to cut it back?

President Donald Trump's efforts to "repeal and replace" the Affordable Care Act shout that the answer is yes.

Before Trump won in November, the GOP House had voted repeatedly to terminate Obamacare; the Senate passed a repeal measure in 2015. When President Barack Obama was around to veto their handiwork, Republicans saw little downside in voting to repeal Obama's signature legislation.

Now that Republicans control the White House, Senate and House, there is no one standing in their way but themselves. House Speaker Paul Ryan corralled the votes needed to pass a measure in the House. It wasn't easy.

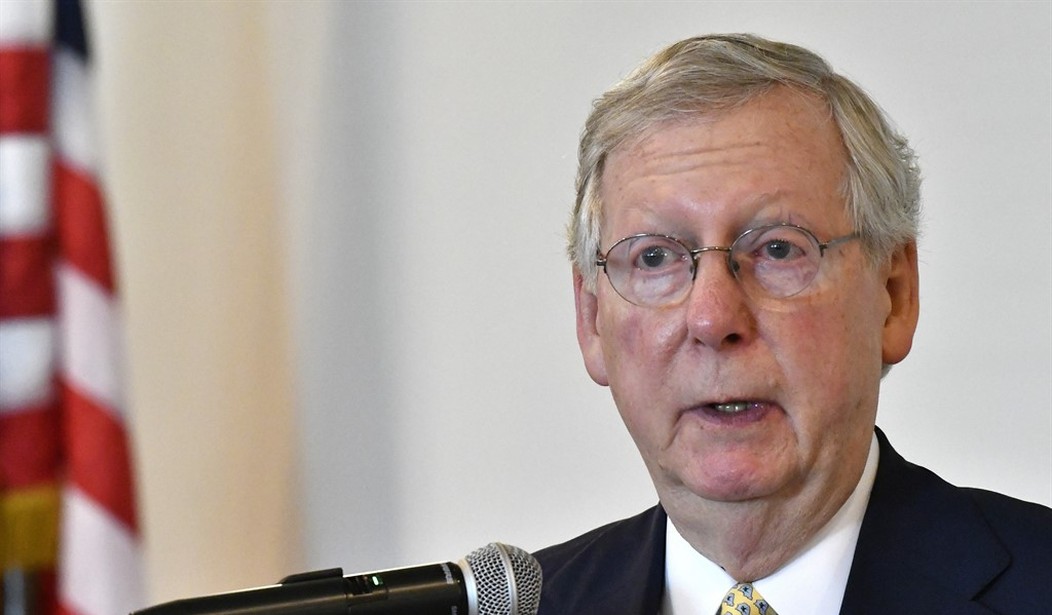

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell tried to herd 52 GOP senators behind a Senate version of Trumpcare. Like Ryan, he watched as what was done to woo moderates cost support from the GOP base. What pleased the hard-liners horrified the moderates. Four senators announced they'd oppose the Better Care Reconciliation Act, and that was that.

So McConnell proposed a vote on a straight-up repeal of Obamacare. That should be a smart move -- 52 Republicans passed such a bill in 2015. But Tuesday three GOP senators scotched that idea, including two senators -- Lisa Murkowski of Alaska and Shelley Moore Capito of West Virginia -- who voted to repeal Obamacare in 2015. Still, McConnell is expected to put a repeal-only measure to a vote next week and it is expected to fail.

"In some ways, it took everyone by surprise" that the GOP efforts failed, said Center on Budget and Policy Priorities senior fellow Aviva Aron-Dine, but "in other ways it seems baked in." Voters "overwhelmingly didn't want to see it repealed and replaced."

Recommended

Over the last six months, voters started to like the formerly unpopular package. The Kaiser Family Foundation found that 51 percent of voters viewed Obamacare favorably, and 41 percent did not.

"It's hard to get rid of everything," Tea Party Express chief strategist Sal Russo observed. "Every program has something for somebody."

Galen Institute senior fellow Doug Badger explained the two facets of the Affordable Care Act -- "what you're taking away from roughly 16 million people who are gaining coverage or what you're doing to the tens of millions of people" who are priced out of the market or are paying more for less coverage.

"It's a fight about money," said Badger.

Democrats shrewdly gave federal dollars to states that expanded Medicaid coverage to able-bodied childless adults -- that assured the support of governors who opted into that plan. Nevada Gov. Brian Sandoval signed on in order to get coverage for 210,000 Nevadans.

Sandoval joined 10 other governors in a bipartisan statement that urged the Senate to "immediately reject efforts to 'repeal' the current system and replace some time later." At a joint press conference with Sandoval in June, Sen. Dean Heller, R-Nev., announced his opposition to the Senate bill. Once legislation has been given life, it is hard to kill.

"I'm all for jockeying to get your position and holding out for one thing or another," Russo opined, "but at the end of the day, you've got to succeed. People will accept progress. What they don't accept is doing nothing."

Trump invited all 52 GOP senators to lunch Wednesday at the White House. Maybe he's learning he needs help to get these things done.

At last year's Republican National Convention, Trump derided a dysfunctional Washington, and crowed, "I alone can fix it."

Tuesday, Trump ceased to be a solo act. Deputy Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders chastised the minority party for refusing "to join in fixing the health care problems."

Trump told reporters, "I'm not going to own it. I can tell you, the Republicans are not going to own it."

It was an odd admission coming from a president who threw a celebration in the Rose Garden when the GOP House passed its Trumpcare bill, only to call the measure "mean" a month later.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member