In her brief press conference at the United Nations, Hillary Clinton led off with a denunciation of the letter to Iranian leaders signed by 47 of the 54 Republican senators. This was in line with Democratic talking points -- a sign that the former secretary of state was, perhaps a bit nervously, taking care to curry favor with the Obama administration.

Clinton's criticism was more muted than that of many Democrats, administration spokesmen and the president himself. Democrats encouraged supporters around the country to sign an online petition calling the letter "treason."

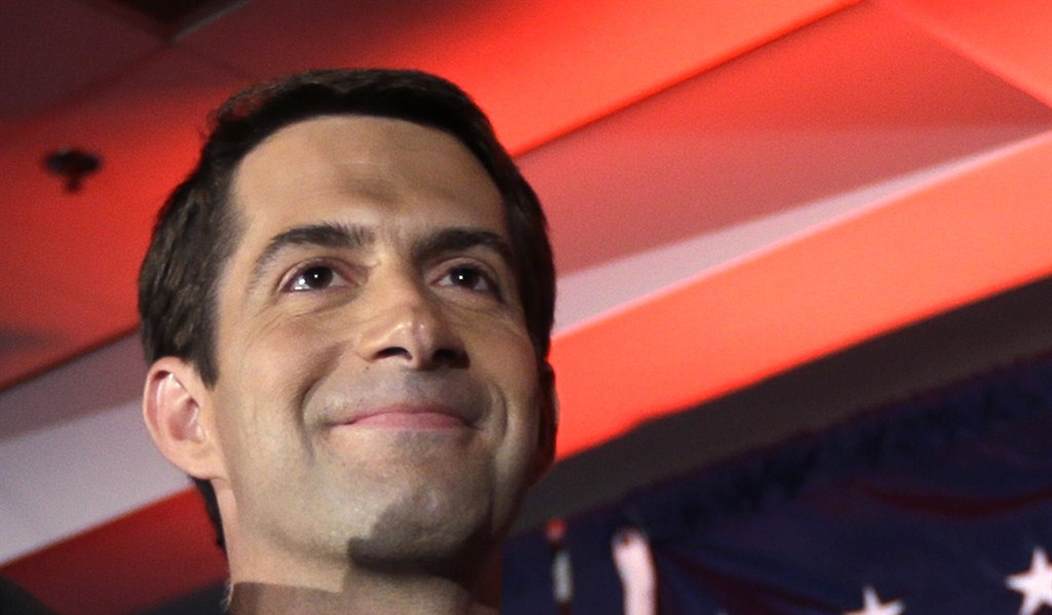

The letter in question, spearheaded by freshman Tom Cotton, simply pointed out that any agreement signed by President Obama but not approved by Congress would not be binding on the next president.

That shouldn't be controversial. As Secretary of State John Kerry noted in a Senate hearing, such an agreement would not be "a legally binding plan." Just as George W. Bush's written assurances to Israel's prime minister in 2004 have not been considered binding by Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton.

This is of course not the first time members of Congress in disagreement with administration policies have reached out to foreign leaders. There was Speaker Nancy Pelosi's 2007 visit with Bashar al-Assad in Syria, for example. Or Edward Kennedy's behind-the-scenes reach-out to Soviet leaders on how to resist Ronald Reagan's policies.

All these were sparked by nontrivial disagreements on foreign policy between elected members of Congress and elected presidents. So it is here. The disagreement now is not just over negotiating tactics but over the nature of the Iranian regime.

Obama supporters have called Cotton "Tehran Tom" and said that the letter strengthens the position of Iranian "hardliners." This makes sense if you believe, as Obama apparently does, that some current leaders of the Iranian government yearn for a grand bargain with the United States and want to make Iran a normal country.

Recommended

The 47 senators who signed the letter and many other members of Congress -- including many Democrats as well as Republicans -- take a different view. They might concede that Iranian President Hassan Rouhani and Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif have been uttering honeyed words to American negotiators behind the scene.

But they note that the final say in Iran belongs to the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei. And they remember that for more than 35 years, Iran has been a leading sponsor of terror, an armed and deadly enemy of United States military forces and a nation whose leaders contemplate with pleasure the destruction of Israel.

They see Iran extending its influence across the Middle East, bucking up Assad in Syria and supporting Hezbollah forces on the border of Israel. They see Iran's military forces leading in battle against the Islamic State in Iraq, and note that administration spokesmen view this with equanimity.

That's not the view of most members of Congress. They see expansion of Iranian power into an Iraq from which U.S. forces withdrew when Obama refused to push for a status of forces agreement as profoundly disturbing. In this case, at least they agree with Benjamin Netanyahu's statement, in his speech to Congress, that the enemy of my enemy is my enemy.

The president has made it clear he won't submit any agreement to Congress for approval, and his spokesmen have made feints at suggesting he would seek approval, in the hopes of some measure of permanence, by the United Nations Security Council.

He is evidently ready to acquiesce to an expansion of Iranian power in the Middle East and a green light for Iran to obtain a bomb in 10 years, on the assumption that the character of the regime has changed sufficiently to render it tolerable.

Neither Saudi Arabia and other Arab neighbors nor Israel considers that desirable. Neither do most of members of Congress or, to judge from polls, most American voters.

This is not the first time a Congress has been at odds with a president's foreign policy and has tried to push back. That was the case in back in 2007 and 2008, when most members of the Democratic Congress opposed George W. Bush's surge strategy in Iraq, which contrary to their predictions, succeeded.

Barack Obama threw that victory away and now seems complacent about Iran's advances beyond its borders. Telling Iran's leaders that most in Congress and most Americans disagree and that an agreement may not last is just highlighting what should be obvious.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member