Editor's Note: Due to Big Tech's strict policies and the graphic nature of the content, there are no ads on this article. Please join Townhall VIP to support our investigative reporting and ensure stories like this one are told.

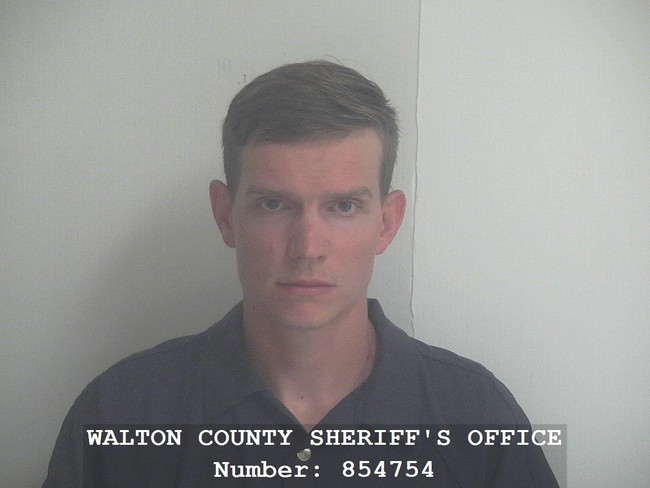

For the first time following Townhall's bombshell investigation into a suburban LGBTQ pedophile ring near Atlanta, gay activists turned-alleged child rapists Zachary and William Zulock, who are accused of sexually abusing their adopted sons, made physical appearances in the courtroom for separate motion hearings on Feb. 1 as the Georgia child-prostitution case gears up for trial.

There, during back-to-back court proceedings, Judge Jeffrey Foster considered Walton County District Attorney Randy McGinley's motion for the restriction of "extrajudicial statements," commonly referred to as a gag order, and cautioned that the same-sex couple's not-so-private communications from behind bars have been made public by a family whistleblower of sorts.

The judge's warning came after Townhall published Zachary and William's recorded jailhouse calls and text conversations with a concerned family member, who shared the material exclusively with Townhall to shine a spotlight on the Zulock case that has seen an all-out media blackout—at the local and national level—since news of the married men's arrests broke over the summer.

TAPES: @MiaCathell investigated a suburban LGBTQ pedophile ring. Here's what she discovered. pic.twitter.com/O7NWtx5Q8K

— Townhall.com (@townhallcom) January 17, 2023

"My instinct is that much of what is out there was conversation that was assumed to be in confidence that, obviously, was not held in confidence," Foster, alluding to the leaked calls and chats, stated. "I'm sure, after discussions with counsel, the nature of any exchanges and conversations with family members would probably be much more guarded, in light of the circumstances now anyway." The judge underscored: "But, I can't compel third parties who would become aware of information to not say anything."

Recommended

Immediately after Foster warned the Zulock men against speaking about their criminal case to third parties, the co-defendants—left dumbfounded by the prosecution dangling the threat of a gag order—both blabbed anyways in spite of the judge's advice.

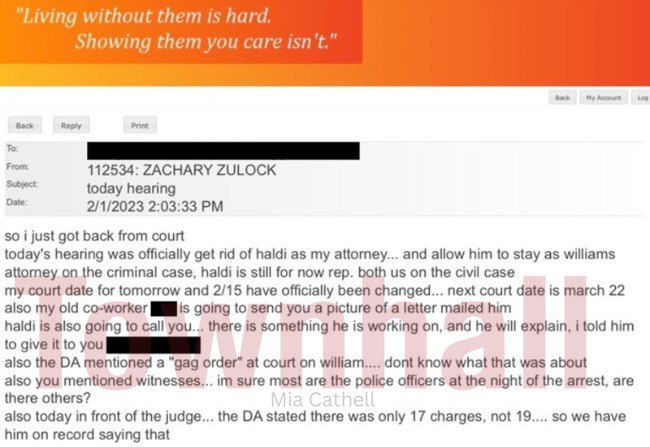

Zachary logged into his digital tablet and typed lengthy tell-all texts to the very relative who's been providing Townhall with copies of their conversations, about two hours after the judge forewarned the Zulock co-defendants to be wary of any outside contact.

"So I just got back from court," wrote Zachary, promptly upon returning to Barrow County Detention Center where he's being held apart from William. "also the DA mentioned a 'gag order' at court on william....dont know what that was about," Zachary pondered.

Zachary also questioned who the state's witnesses are and suspected that most were part of the armed SWAT team that raided the Zulock mansion in the late July rescue mission. "are there others?" Zachary wondered in his initial message on Feb. 1.

The state's current list of witnesses includes the 9- and 11-year-old boys that the adoptive fathers allegedly raped, filmed their violent and "routine" sexual abuse of, and offered up to other strange men in the area; special agents with the Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI)'s Child Exploitation And Computer Crimes (CEACC) Unit; and the sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) who performed the forensic rape examinations on the two children—one of which endured extensive injuries from the anal rape.

Zachary immediately reacted to the Feb. 1 motion hearings

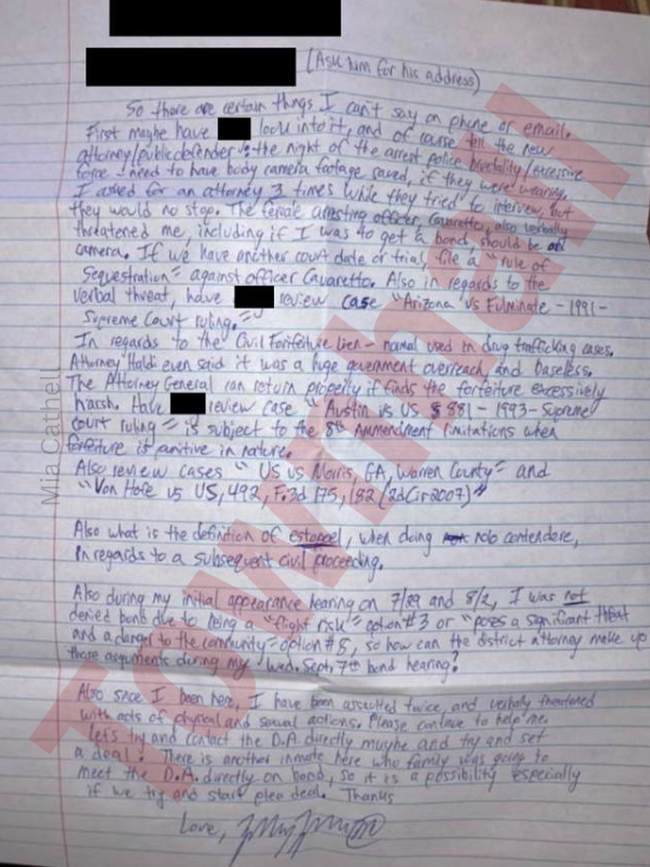

While in pre-trial detainment, Zachary also contacted an "old co-worker" on the outside by passing a handwritten letter to a fellow inmate, who then screenshot and forwarded along the message via email, in an apparent attempt to circumvent the county jail's surveillance of correspondence beyond its walls. Zachary's confidential note jotted down in blue ink on lined notebook paper contains a series of instructions that reveal his legal strategy, according to a copy of the undated letter Townhall has obtained.

"So there are certain things I can't say on phone or email," Zachary wrote to his former colleague, who has a legal background. He first beseeched that the associate asks an old roommate to "look into" obtaining the police body-worn camera footage on the night of the raid when officers "slammed" Zachary on the floor of their foyer, leaving the jailbird with a bruise on his left cheek.

William was simultaneously arrested bare-naked in bed and sat nude in the back of a patrol car as the children were rescued.

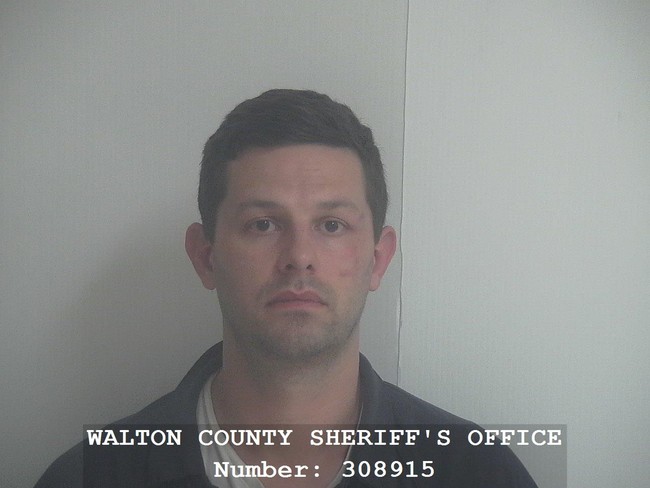

Zachary's bruised face is visible in his Walton County Jail mugshot

Zachary claimed he's a victim of "police brutality" and that the swarm of law enforcement officers used "excessive force."

"I asked for an attorney 3 times while they tried to interview, but they would not stop," Zachary alleged in the six-paragraph letter. "The female arresting officer, Caveretto, also verbally threatened me, including if I was to get a bond, should be on camera."

Zachary demanded that the rule of sequestration, which prevents a witness's testimony from influencing another witness who has not yet testified, be invoked against Det. Kristilee Cavoretto, the Walton County Sheriff's Office (WCSO) detective leading the Zulock investigation and a name placed near the top of the state's 21-person witness list, among the other WCSO investigators.

In regards to "the verbal threat," Zachary exhorted that his friends review Arizona v. Fulminante, a 1991 U.S. Supreme Court ruling, which found that a convicted child murderer, whose conviction relied on confessions he made to a paid Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) informant who promised the defendant protection from vigilante inmates in exchange for the truth, was coerced to confess for "fear of physical violence," affirming the state's Supreme Court judgment reversing the man's conviction.

Police statements allege that, in a Mirandized confession, Zachary identified himself as the cameraman who produced the child pornography and distributed it to nearly "a dozen people." During an audio-video police interrogation, William admitted to forcing their 11-year-old son to perform "oral copulation" with the intention to "satisfy his own...sexual desire," a sworn affidavit says.

Zachary's handwritten letter to an "old co-worker"

Regarding the lien on their two-acre mansion and the state's civil complaint seeking to forfeit the house, Zachary claimed that Georgia's attorney general can return forfeited property if he finds the forfeiture "excessively harsh." The couple's defense attorney John E. Haldi has told the court that he's "never seen anything like it outside the drug trafficking context," deeming the move "a huge government overreach" and "baseless," as Zachary recalls. Georgia state law O.C.G.A. § 16-14-7 stipulates that property used in "a pattern of racketeering activity" shall be subject to forfeiture and any assets are declared to be contraband.

Before a grand jury returned the 17-count indictment in the Zulock case, prosecutors were possibly proceeding forward under the child sex trafficking statute of the state's Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act, although RICO Act violations weren't charged. Two counts of human trafficking for sexual servitude have been recently added to the slew of felonies Zachary is already accused of, according to an order summoning the co-defendant to the Walton County courthouse on Feb. 1.

Two felony counts of human trafficking for sexual servitude have since been tacked on to the 17 other child sex crimes Zachary is already accused of committing against his special-needs adopted sons. pic.twitter.com/coxZXV0FGo

— Mia Cathell (@MiaCathell) February 1, 2023

Along with the handful of other cases, Zachary wants his chums to analyze the 1993 U.S. Supreme Court ruling Austin v. United States, which held that the Eighth Amendment's Excessive Fines Clause did apply because the forfeiture was punitive in nature.

Zachary also inquired about estoppel, a principle that precludes an individual from asserting something contrary to what is implied by a previous action or statement, in the context of a nolo contendere plea, a.k.a. a no-contest plea, where a defendant decides not to contest the charges and to accept the punishment as a midway between pleading guilty or not guilty—the latter of which the Zulock co-defendants have pled. Zachary specified he means applying the judicial device in a follow-up civil proceeding.

Imprisoned on a bench warrant, Zachary has repeatedly begged for Haldi to "work a deal" with the district attorney to bond him out of jail. "I want an ankle monitor, and if required, a low bond," Zachary insisted in November, though at the September bond hearing, Judge Foster denied both of the Zulocks bond, determining that the men are flight risks, "a risk of danger to children in the community," and could intimidate the witnesses or victims. Zachary alleged that DA McGinley "made up these arguments."

"...[S]ince I have been here, I have been assaulted twice, and verbally threatened with acts of physical and sexual actions," Zachary wrote to the old co-worker. Part 4 of Townhall's investigation captured a glimpse of the jail justice Zachary is receiving in the slammer. In his own words, Zachary has vividly described the anti-"ChoMo" (child molester) treatment he's been experiencing at rock bottom of the inmate food-chain, claiming in October that a cellmate drugged him and sent him to the clink's infirmary.

"he needs to get me out," Zachary texted, pleading for his criminal defense lawyer to "work [out] a deal."

— Mia Cathell (@MiaCathell) January 20, 2023

"tell DA that I want an ankle monitor, and if required, a low bond," demanded Zachary, who was told that the judge would "laugh him" out of the courtroom. pic.twitter.com/Rrf4VbeEhI

Zachary, who is facing life in prison, appears to be considering negotiating a plea agreement for a reduced sentence. "Please continue to help me. Let's try and contact the DA directly maybe and try to set a deal," Zachary penned. "There is another inmate here who [sic] family was going to meet the DA directly on bond, so it is a possibility especially if we try and start [a] plea deal."

He signed the secret note: "Love, Zachary Zulock."

It seems Zachary was trying to take matters into his own hands by personally reaching out to McGinley to either arrange bond or a plea deal without a lawyer present. Haldi "did my [sic] ZERO justice over the months...only visited 4 times, and never discussed the case or charges or anything...he never even fought for a bond," Zachary later texted his family member in the following days.

"Mr. Zulock has attempted to contact my office numerous times," McGinley said in court. "And my office is not being rude by not responding, but ethically—he's indicated he wants to be represented. And so, therefore, it would be inappropriate of my office to speak to Mr. Zulock. I want to make sure he's aware of that." Foster affirmed that the bar rules prohibit such communication.

"But, you need to understand that in the communications that you make or that you relay are matters that, of course, if there's any statements or admissions in those, those things can be used against you in future proceedings," Foster instructed a fidgeting Zachary, who twiddled his thumbs. "So, proceed cautiously and speak little and wait for new counsel to get involved in the case."

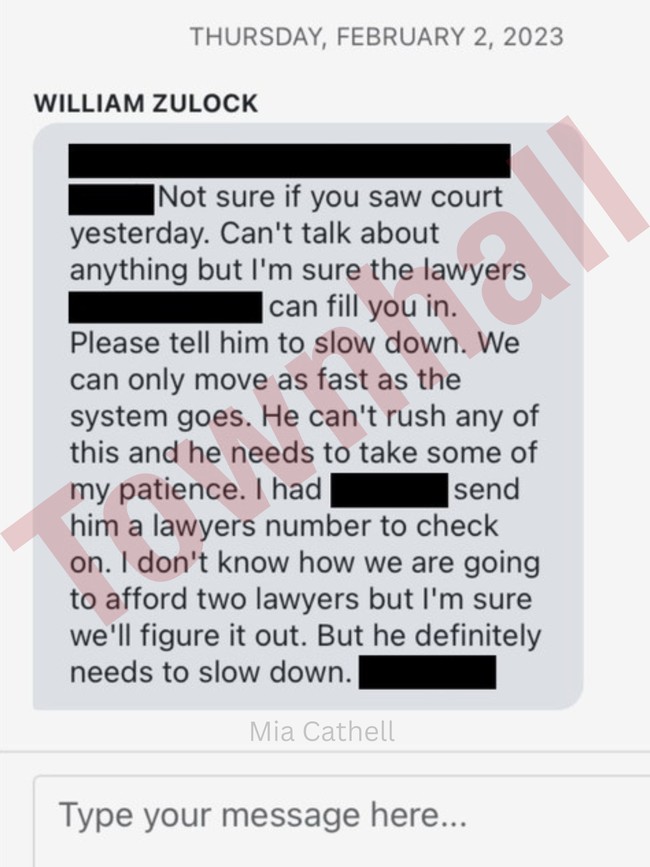

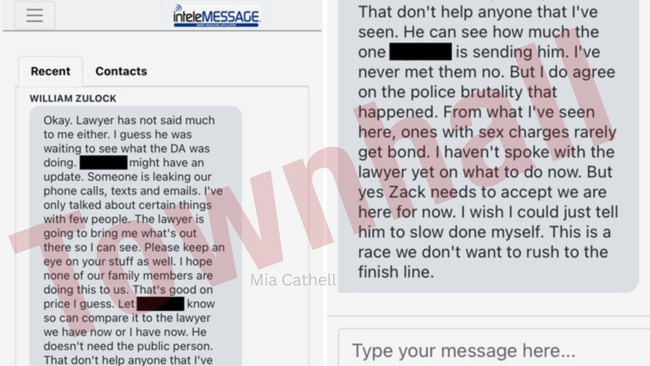

Zachary's jailed husband William, too, ran his mouth to Townhall's anonymous source within the Zulock family. Initially unbothered by Foster's advisory, William was more concerned about Zachary's panicked state of mind than heeding the judge's guidance.

"Please tell him to slow down..." William said of Zachary. "He can't rush any of this and he needs to take some of my patience."

William's Feb. 2 text expressing concern for Zachary's mental state

"...Zack needs to accept we are here for now. I wish I could tell him to slow down myself. This is a race we don't want to rush to the finish line," William wrote in another Feb. 2 text to the relative on the inmate-messaging app where he, then, expressed disbelief that "Someone is leaking our phone calls, texts and emails." Unbeknownst to William, he was texting that someone.

William's booking photo taken at Walton County Jail

"I've only talked about certain things with [a] few people. The lawyer is going to bring me what's out there so I can see. Please keep an eye on your stuff as well," William told Townhall's informant. "I hope none of our family members are doing this to us."

William's Feb. 2 text discussing the leaked conversations

When asked if he knew any of Zachary's confidants he addressed in the letter, William said, "I've never met them no." But, William believes that the police officers "brutalized" him and Zachary in their hours-long midnight bust at the Zulock mansion.

These are just a sample of Zachary and William's jail texts Townhall has been provided in the aftermath of the gag-order threat.

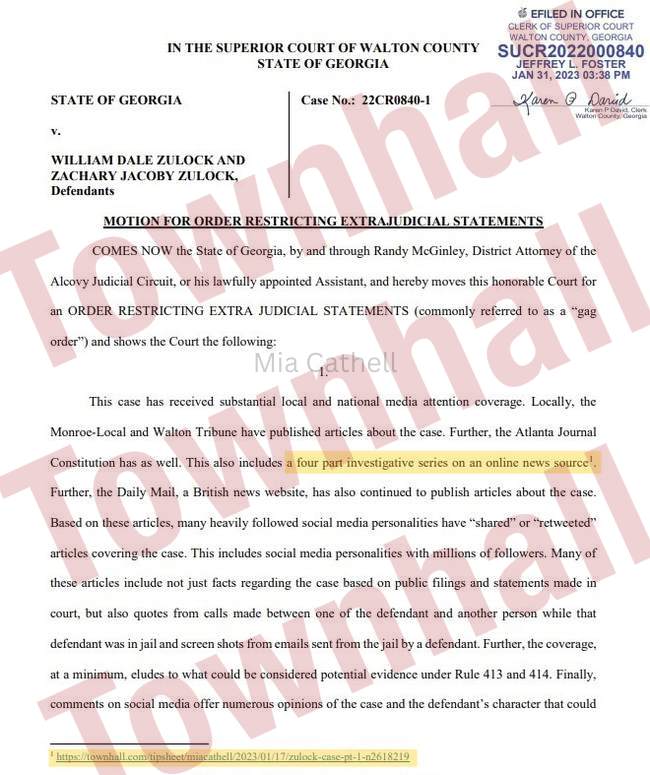

DA McGinley's motion for a gag order cites Townhall's four-part investigative series and points to "heavily followed social media personalities" that have shared or retweeted articles covering the Zulock case, per a copy of the request Townhall has acquired.

Many of the reports not only include facts of the case that Townhall gathered from public filings and statements made in court, but also quotes from the taped calls and screenshots of the text messages between Townhall's family insider and the locked-up Zulock co-defendants, McGinley mentions, linking the first installment of Townhall's explosive exposé in the motion's footnotes.

In addition, comments on social media "offer numerous opinions of the case and the defendant's character that could serve as a reasonable likelihood of prejudicing the right of a fair trial..." McGinley argues in the five-page motion he submitted on Jan. 31.

DA McGinley's motion for a gag order in the Zulock case

Acknowledging the right to freedom of the press under the U.S. Constitution and the state's constitutional protections, McGinley specifies that he does not ask the court, "in any form or fashion," to "restrict the First Amendment rights of the press or media."

Thus, the proposed order would not be imposed on members of the media, McGinley's motion declares.

McGinley urged the court to order that attorneys from all parties be barred from making out-of-court statements on the accused's character and criminal records, the possibility of a plea agreement, opinions on guilt or innocence, and a list of other topics the state wants to have restrictions on to "minimize the effects of prejudicial pretrial publicity." Public-record information is fair game.

"It'd be really hard to enter, in essence, a gag order against involving one co-defendant and one co-defendant's attorney in the state and not, you know, it's sort of like trying to set up a tripod without one of the legs. I don't know that my balance is that good," Foster went on, noting he isn't fully debriefed on the details of the Zulock case. "But I do have to compare it to the standards and the narrowness and the compelling interest [...] I, unusually for me, have not actually read the cases and prepped in advance."

As Townhall previously reported, Haldi moved to withdraw as Zachary's counsel of record in response to McGinley's motions to sever the jointly indicted Zulock co-defendants at trial and disqualify Haldi from representing both spouses. While the criminal defense lawyer was split at first on choosing his sole client, what guided the decision is likely the hefty $50,000 William's side of the family begrudgingly handed Haldi. Foster has formally released Haldi from Zachary's case following the Feb. 1 court date.

To date, the once-wealthy Zachary is lawyer-less, penniless, and in the process of retaining a private attorney despite his lack of funds. For now, Foster recommended that Zachary confer with the public defender's office, although there may be a conflict of interest there given another indigent defendant connected to the Zulock case is already seeking legal services through them.

Foster stressed that he doesn't "have a problem signing an order that says our obligations as professionals are court ordered, because that just means we don't have to wait to go to the bar, but that's our obligations anyway, so that's just sort of saying we all agree we're going to play by the rules we're supposed to play by." Regardless, the judge emphasized, "we're not the issue."

"I will abide by the Rules of Professional Conduct at all times," Haldi replied. "The order to me is a little bit like wearing a belt with suspenders." Foster, chuckling, said that "the only thing the order does" is instead of waiting for a bar complaint to address a matter, it allows the court to act quickly. "It's prophylactic," Foster reiterated. At another point in the back-and-forth discussion, McGinley said, "Mr. Haldi, I don't think has spoken to anybody. So, to make sure it's clear: I wasn't thinking he's done anything wrong at all. But it also just makes it easier for other people to respond in a way that keeps the fairness of the case intact."

Foster agreed that is "ultimately our goal" to be able to select a jury that is as fair and impartial as both parties can gather.

"So, I'm not going to rule on [the gag order] yet," Foster adamantly decided. "I do think opposing counsel probably needs to have in the intervening time period—I trust the agencies involved. Mr. McGinley, if you relay to them that the matter is under consideration [...] I think, largely, it makes it easier for them to say [...] 'We can't comment on a pending case at this point in time.' And we'll sort out what kind of order we need. We'll tailor it as narrowly as possible." Foster also highlighted the court needing input from Zachary's to-be-determined counsel when entered, since he or she "would come into the case and be bound by it."

If severed and limited immunity grants are approved, Zachary and William can be called upon to testify against each other.

Stay tuned for the next update in the Zulock case, to be released on Wednesday, February 22, 2023, revealing a lovers' quarrel brewing between the Zulock men and if the co-defendants could turn on each other. More jail texts to come.

Editor's Note: Townhall's investigative reporting exposing the disgusting, woke ideology of the left would not be possible without the support of our VIP members.

Join Townhall VIP and use promo code INVESTIGATE to support the vital work of Mia Cathell and help us continue to shed light on the darkest parts of the radical left.