Researchers have edited the genes of an embryo in a process called “germline engineering,” for the first time in the U.S.

Scientists hope the controversial practice will lead to correcting genetic diseases in embryos, that will continue to pass on the modified genes to offspring. According to the MIT Technology Review, the researchers used a technique called CRISPR.

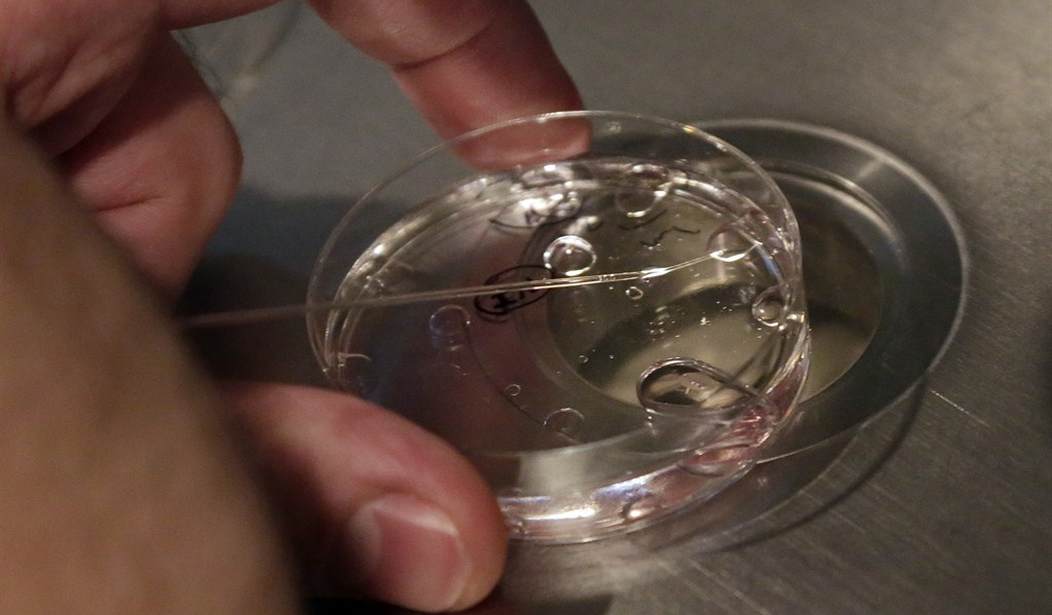

The Review wrote scientists used donated sperm with inherited mutations to create multiple IVF embryos for the sake of the experiment. The embryos only developed for a few days, the scientists not intending they survive or be implanted.

The Portland, Oregon, team was led by Shoukhrat Mitalipov, from Oregon Health and Science University. Mitalipov’s work has been controversial in years past, cloning animals, but also cloning human embryos in 2013.

The advisory committee would not allow embryos to go through genetic enhancements. Alta Charo is a law and bioethics professor at University of Wisconsin-Madison and co-chair of National Academy of Sciences’ study committee. She said, “Genome editing to enhance traits or abilities beyond ordinary health raises concerns about whether the benefits can outweigh the risks, and about fairness if available only to some people.”

Still, many object to genetic editing. According to a Pew Research Center study published a year ago, 28 percent of adults in the U.S. think gene editing is morally acceptable, to reduce "risk of serious diseases and conditions."

Recommended

Last year, James R. Clapper, former director of national intelligence, listed the practice in his “Worldwide Threat Assessment for the US Intelligence Community,” under the category: "Weapons of Mass Destruction and Proliferation."

He writes on genome editing, “Advances in genome editing in 2015 have compelled groups of high-profile US and European biologists to question unregulated editing of the human germline (cells that are relevant for reproduction), which might create inheritable genetic changes. Nevertheless, researchers will probably continue to encounter challenges to achieve the desired outcome of the genome modifications, in part because of the technical limitations that are inherent in available genome editing systems."

Clapper says that harm is increased when conducted in countries that do not have the same standards as "Western countries," and that the quick development, low cost, and the accessibility of the technology could be misused to the detriment of security and economy.

Not only is genetic editing itself controversial, but so also the method of experimentation. According to a YouGov poll conducted near the time an unborn child was murdered in 2015, 52 percent of Americans believe that life begins at conception. Yet, during the experiment, the Portland researchers allowed tens on tens of fertilized embryos to die.

Congress has blocked efforts for an embryo with genetic editing to be implanted and brought to term, turned "into a baby."

While this is the first case in the U.S., MIT Technology Review said previous experiments have been done in other parts of the world, with scientists in China publishing three instances of editing embryos.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member