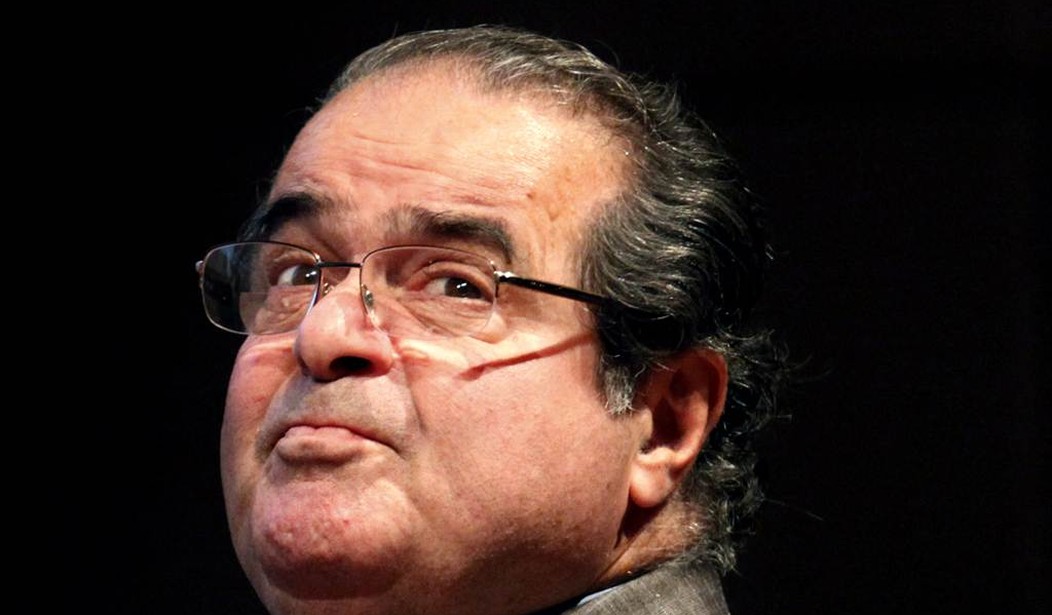

Call it a “Scalia moment.” You are reading the latest opinion of Supreme Court Associate Justice Antonin Scalia and come across a witty line or turn of phrase that makes you laugh aloud, an insight or observation that makes you nod your head in agreement, or a caustic barb that makes you wince for the target. Since his appointment in 1986, Scalia has been the Court’s premier conservative, intellectual gladiator, and chief wordsmith. More than anyone who has served on the High Court in recent history, Scalia has given life to Aristotle’s injunction that “it is not enough to know what to say—one must know how to say it.”1

His words can be pointed. “Today’s opinion has no foundation in American constitutional law, and barely pretends to,” he charged in one case.

Scalia’s opinions can also be witty and humorous. Explaining why he did not think the Court should try to create a standard for defining “literary or artistic value” in an obscenity case, Scalia said “... in my view it is quite impossible to come to an objective assessment of (at least) literary or artistic value, there being many accomplished people who found literature in Dada and art in the replication of a soup can.”3 In another decision, he explained why the Court could comfortably rely on the testimony of witnesses who saw the face of an alleged killer: “Facial features are the primary means by which human beings recognize one another. That is why police departments distribute “mug” shots of wanted felons, rather than Ivy-League-type posture pictures; it is why bank robbers wear stockings over their faces instead of floor-length capes over their shoulders; it is why the Lone Ranger wears a mask instead of a poncho; and it is why a criminal defense lawyer who seeks to destroy an identifying witness by asking ‘You admit that you saw only the killer’s face?’ will be laughed out of the courtroom.”

His humor is often subtle. Consider his explanation of the proper meaning of the term, “modify.” “‘Modify,’ in our view, connotes moderate change. It might be good English to say that the French Revolution ‘modified’ the status of the French nobility—but only because there is a figure of speech called understatement and a literary device known as sarcasm.”5

Recommended

Scalia can use words to create vivid images that help communicate his arguments. In one case, rather than simply admonish the Court for its selective use of the oft-criticized Lemon test, which was created to identify government action that violates the religious Establishment Clause (see chapter seven), Scalia wrote, “Like some ghoul in a late night horror movie that repeatedly sits up in his grave and shuffles abroad, after being repeatedly killed and buried, Lemon stalks our Establishment Clause jurisprudence once again, frightening the little children and school attorneys of Center Moriches Union Free School District.”

In addition, Scalia has a talent for putting complex arguments about fundamental principles in easy-to-understand terms. Slicing through the various First Amendment analyses that might be applied to determine the speech rights of the religious, Scalia concluded, “A priest has as much liberty to proselytize as a patriot.” In another case, while arguing for freedom of political parties to set their own rules of organization, Scalia wrote, “A freedom of political association that must await the Government’s favorable response to a ‘Mother, may I?’ is not freedom of political association at all.”

Finally, as even casual followers of the Supreme Court know, Scalia’s words can reveal his outrage at the decisions reached and lack of judicial restraint demonstrated by his colleagues on the High Court. Scalia concluded one opinion, “The Court must be living in another world. Day by day, case by case, it is busy designing a Constitution for a country I do not recognize.”

Scalia’s way with words is what makes this possible. His opinions—though full of legal arguments and analyses only a lawyer could love—are highly readable. His entertaining writing style can make even the most mundane areas of the law interesting. It is no small feat.

Justice Antonin Scalia is a verbal craftsman. His mastery of language and respect for words carry over into his judicial philosophy. That philosophy is fairly simple and straightforward, and he has explained and championed it in his opinions, public speeches, and even a book. As with his memorable opinions, the primary focus of Scalia’s philosophy is words.

Scalia is a self-proclaimed “textualist.” He believes laws—and especially that supreme law known as the Constitution of the United States—say what they mean and mean what they say. In short, when interpreting the Constitution, Scalia thinks judges should focus on the text. If someone claims he or she is being denied the exercise of a right or if the government asserts it has authority to take a given action, courts must make certain there is specific textual support for each assertion.

In applying his unique judicial philosophy, Scalia bucks some modern trends in constitutional interpretation. Chief among those theories is that of a “living” Constitution. The idea is that the document’s meaning changes from age to age to accommodate the evolving values of the American people.11 This view of constitutional interpretation, which is shared to some extent by nearly all liberal legal scholars, gives judges tremendous power. After all, it is the judge who gets to decide which rights and responsibilities are valued by the public and which ones can be discarded. The obvious danger in such an approach is that the rule of law becomes rule by lawyers.

In politically incorrect splendor, Scalia says he likes his Constitution “dead.” He argues that only a fixed and enduring charter can keep judges from reading new fads into the Constitution and less popular mandates out.

Editor's note: This column is an exclusive excerpt from "Scalia Dissents: Writings of the Supreme Court's Wittiest, Most Outspoken Justice."

Join the conversation as a VIP Member