Most of us will never be directly impacted by the international provisions of the internal revenue code.

That’s bad news because it presumably means we don’t have a lot of money, but it’s good news because IRS policies regarding “foreign-source income” are a poisonous combination of complexity, harshness, and bullying (this image from the International Tax Blog helps to illustrate that only taxpayers with lots of money can afford the lawyers and accountants needed to navigate this awful part of the internal revenue code).

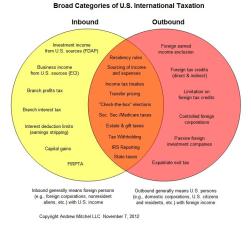

(this image from the International Tax Blog helps to illustrate that only taxpayers with lots of money can afford the lawyers and accountants needed to navigate this awful part of the internal revenue code).

But the bullying and the burdens aren’t being imposed solely on Americans. The internal revenue code is uniquely unilateral and imperialistic, so we simultaneously hurt U.S. taxpayers and cause discord with other jurisdictions.

Here are some very wise words from a Washington Post column by Professor Andrés Martinez of Arizona State University.

Much of his article focuses on the inversion issue, but I’ve already covered that topic many times. What caught my attention instead is that he does a great job of highlighting the underlying philosophical and design flaws of our tax code. And what he writes on that topic is very much worth sharing.

Recommended

The Obama administration is not living up to its promise to move the country away from an arrogant, unilateral approach to the world. And it has not embraced a more consensus-driven, multipolar vision that reflects the fact that America is not the sole player in the global sandbox. No, I am not talking here about national security or counter-terrorism policy, but rather the telling issue of how governments think about money — specifically the money they are entitled to, as established by their tax policies. …ours is a country with an outdated tax code — one that reflects the worst go-it-alone, imperialistic, America-first impulses. …the…problem is old-fashioned Yankee imperialism.

What is he talking about? What is this fiscal imperialism?

It’s worldwide taxation, a policy that is grossly inconsistent with good tax policy (for instance, worldwide taxation is abolished under both the flat tax and national sales tax).

He elaborates.

The United States persists in imposing its “worldwide taxation” system, as opposed to the “territorial” model embraced by most of the rest of the world. Under a “territorial” tax system, the sovereign with jurisdiction over the economic activity is entitled to tax it. If you profit from doing business in France, you owe the French treasury taxes, regardless of whether you are a French, American or Japanese multinational. Even the United States, conveniently, subscribes to this logical approach when it comes to foreign companies doing business here: Foreign companies pay Washington corporate taxes on the income made by their U.S. operations. But under our worldwide tax system, Uncle Sam also taxes your income as an American citizen (or Apple’s or Coca-Cola’s) anywhere in the world. …Imagine you are a California-based widget manufacturer competing around the world against a Dutch widget manufacturer. You both do very well and compete aggressively in Latin America, and pay taxes on your income there. Trouble is, your Dutch competitor can reinvest those profits back in its home country without paying additional taxes, but you can’t.

Amen.

Indeed, if you watch this video, you’ll see that I also show how the territorial system of the Netherlands is far superior and more pro-competitive than America’s worldwide regime.

And if you like images, this graphic explains how American companies are put at a competitive disadvantage.

Professor Martinez points to the obvious solution.

Instead of attacking companies struggling to compete in the global marketplace, the Obama administration should work with Republicans to move to a territorial tax system.

But, needless to say, the White House wants to move policy in the wrong direction.

Looking specifically at the topic of inversions, the Wall Street Journal eviscerates the Obama Administration’s unilateral effort to penalize American companies that compete overseas.

Here are some of the highlights.

…the Obama Treasury this week rolled out a plan to discourage investment in America. …the practical impact will be to make it harder to make money overseas and then bring it back here. …if the changes work as intended, they will make it more difficult and expensive for companies to reinvest foreign earnings in the U.S. Tell us again how this helps American workers.

The WSJ makes three very powerful points.

First, companies that invert still pay tax on profits earned in America.

…the point is not to ensure that U.S. business profits will continue to be taxed. Such profits will be taxed under any of the inversion deals that have received so much recent attention. The White House goal is to ensure that the U.S. government can tax theforeignprofits of U.S. companies, even though this money has already been taxed by the countries in which it was earned, and even though those countries generally don’t tax their own companies on profits earned in the U.S.

Second, there is no dearth of corporate tax revenue.

Mr. Lew may be famously ignorant on matters of finance, but now there’s reason to question his command of basic math. Corporate income tax revenues have roughly doubled since the recession. Such receipts surged in fiscal year 2013 to $274 billion, up from $138 billion in 2009. Even the White House budget office is expecting corporate income tax revenues for fiscal 2014 to rise above $332 billion and to hit $502 billion by 2016.

Third, it’s either laughable or unseemly that companies are being lectured about “fairness” and “patriotism” by a cronyist like Treasury Secretary Lew.

It must be fun for corporate executives to get a moral lecture from a guy who took home an $800,000 salary from a nonprofit university and then pocketed a severance payment when he quit to work on Wall Street, even though school policy says only terminated employees are eligible for severance.

Heck, it’s not just that Lew got sweetheart treatment from an educational institution that gets subsidies from Washington.

The WSJ also should have mentioned that he was an “unpatriotic” tax avoider when he worked on Wall Street.

But I guess rules are only for the little people, not the political elite.

P.S. Amazingly, I actually found a very good joke about worldwide taxation. Maybe not as funny as these IRS jokes, but still reasonably amusing.

P.P.S. Shifting from tax competitiveness to tax principles, I’ve been criticized for being a squish by Laurence Vance of the Mises Institute. He wrote:

Mitchell supports the flat tax is “other than a family-based allowance, it gets rid of all loopholes, deductions, credits, exemptions, exclusions, and preferences, meaning economic activity is taxed equally.” But because “a national sales tax (such as the Fair Tax) is like a flat tax but with a different collection point,” and “the two plans are different sides of the same coin” with no “loopholes,” even though he is “mostly known for being an advocate of the flat tax,” Mitchell has “no objection to speaking in favor of a national sales tax, testifying in favor of a national sales tax, or debating in favor of a national sales tax.” But as I havesaid before, the flat tax is not flat and the Fair Tax is not fair. …proponents of a free society should work towardexpandingtax deductions, tax credits, tax breaks, tax exemptions, tax exclusions, tax incentives, tax loopholes, tax preferences, tax avoidance schemes, and tax shelters and applying them to as many Americans as possible. These things are not subsidies that have to be “paid for.” They should only be eliminated because the income tax itself has been eliminated. …the goal should be no taxes whatsoever.

In my defense, I largely agree. As I’ve noted here, here, here, and here, I ultimately want to limit the federal government to the powers granted in Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution, in which case we wouldn’t need any broad-based tax.

Though I confess I’ve never argued in favor of “no taxes whatsoever” since I’m not an anarcho-capitalist. So maybe I am a squish. Moreover, Mr. Vance isn’t the first person to accuse me of being insufficiently hardcore.