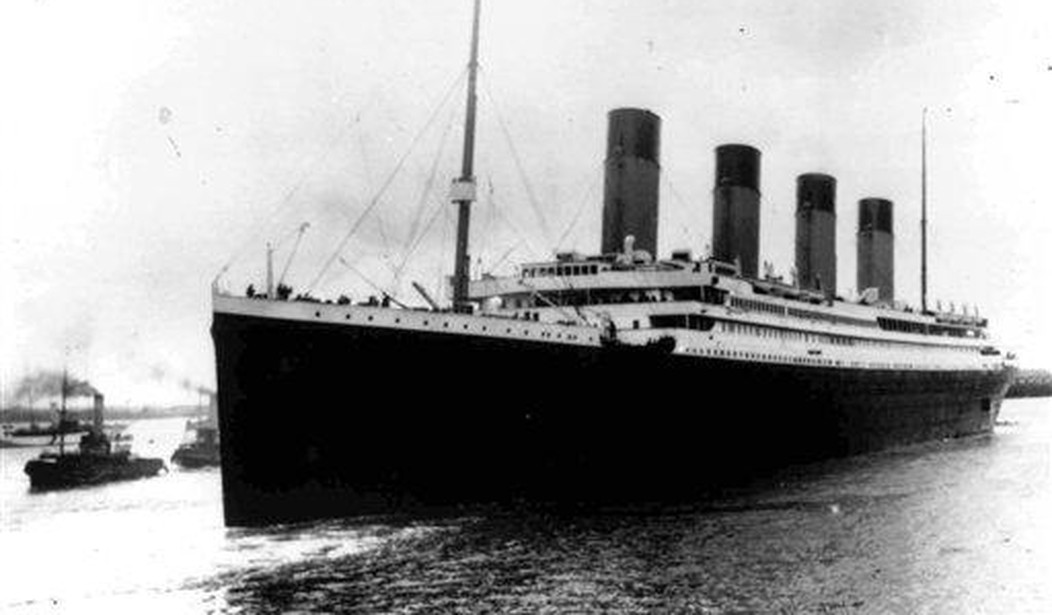

A video of violinists wearing life jackets in the toilet paper aisle of a grocery store went viral on St. Patrick’s Day—it exemplifies how people are experiencing similar fears to those who were aboard the Titanic on April 14, 1912. Many inspiring heroes emerged that night, and their stories are powerful lessons for us, 108 years later, during these uncertain days.

Margaret (“Molly”) Brown

In the Titanic lifeboats, and even in years after the disaster, one of the most remarkable heros was Margaret (“Molly”) Brown. In August 1987, about 453 miles south of Newfoundland, a diver found a gold nugget necklace. Some believe the necklace belonged to Molly. As a little girl growing up in Hannibal, Missouri, Molly helped support her family by stripping tobacco leaves. Her father was an Irish immigrant ditch digger, and Molly married a man who worked in the silver mines. He struck gold shortly into their marriage, making them incredibly wealthy overnight, however Molly always said: “I’d rather marry a poor man that I love than a rich man that I didn’t.”

In Titanic lifeboat 6, Molly persisted in her care for others. Titanic quartermaster Robert Hichens was steering the ship when it hit the iceberg, and Molly would later say that he was a “bully” in the lifeboat. They quarreled over his reluctancy to pick up more passengers. However, Molly kept her focus while in the lifeboat, and helped women stay warm by encouraging them to row.

Aboard the rescue ship Carpathia, Margaret distributed food, handed out cups of drinks and passed out blanket after blanket. While still on board, she organized a fund drive for those who would be most in need when they reached New York City. The Survivor’s Committee raised nearly $10,000. Today, this would be worth almost $250,000.

Unable to testify in the U.S. Senate hearings, because she was a woman, she persisted in doing whatever she could. She helped establish the Titanic Memorial in Washington, D.C. and galvanized others in the fight for workers’ rights, women’s rights and education. She worked to start the first juvenile court and helped organize the National American Women’s Suffrage Association. Even before the Nineteenth Amendment, Margaret ran for office— for a seat in the Colorado state Senate in 1901, and in 1914, two years after surviving the Titanic, for a seat in the U.S. Senate.

Margaret organized an international women’s rights conference in Newport, Rhode Island in 1914 and started a support branch for relief for soldiers in France during WWI. She lived until 1932.

Charles Joughin

Weeks after the Titanic sank, head baker Charles Joughin told British inquiry officials that, at one point, he went down to his bunk to “have a nip.” The harsh reality he faced beforehand one of those final sips of what was possibly his own homemade concoction, distilled in his crew quarters, was incredible. Charles directed his crew to load the lifeboats and he assisted in loading the lifeboats with passengers. He had worked on ships since he was a little boy, and knew his disaster checklist well. He was assigned to crew lifeboat 10. But after he helped fill up lifeboat 10 he was not given the direction to board and staff it as crew. Realizing the grave peril of his situation, Charles sprang into action. He threw as many of the enormously heavy chairs from the deck out into the Atlantic. He threw them as far out into the water as he could– far enough away from the ship to hopefully avoid the suction that would occur when she went completely under. He sacrificed strength that he would likely need later in the water.

Charles survived the sinking of the Titanic. Back at home, he rarely talked about the Titanic, and when he did, he turned his story into a whimsical tale to shield the children – for whom he relished in making Christening cakes, chocolate eclairs and more. “I knew it was an iceberg,” he told the children, “because I saw a polar bear, and he waved at me.”

Charles went back to life at sea, and survived the fire on the SS Congress in Coos Bay, Oregon, on Thursday, September 14, 1916. Charles moved to Paterson, New Jersey and lived until 1956.

Veronica Hinke is the author of The Last Night on the Titanic: Unsinkable Drinking Dining and Style.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member