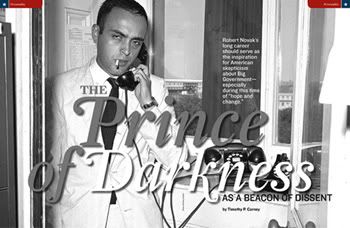

Editor's Note: This special feature on Robert Novak first appeared in the March 2009 issue of Townhall Magazine.

Robert David Sanders Novak has been called many names. His close friends call him “Bob.” Most people call him “Novak.” His wife calls him “Robert.”

Keith Olbermann has called him “The Worst Person in the World.” His more petulant critics have viler names for him. Many critics and admirers have called him “The Prince of Darkness.”

I have had the honor of calling him “Boss.” Since I went to work for him at the end of 2001, Novak has been a mentor and a friend. I learned a lot at his side, but all journalists—and all Americans, for that matter—could learn important lessons from this man, now retired and ill.

Recommended

In these days of single-party rule and a media that fawns over the president, we can all stand a dose of his pervasive skepticism, distrust of those in power and doggedness to dig up the hard facts

A REPORTER ON THE OPINION PAGE

Many people know Novak primarily from his long stint on CNN, but I think it bothers Novak—it always bothers me—when people describe him as a television commentator instead of as a columnist.

To some extent it’s understandable: People watch television more than they read newspapers. Even when people read your work in print, they often don’t bother checking the byline. On TV, they can’t help but see your face.

So, while Novak’s fame primarily resulted from his on-screen work, his real vocation was the written word. And although his work was found exclusively on the opinion pages for the last 45 years of his career, he was a political reporter more than anything else. Sure, he has always had his opinions—and over his life, he has become progressively more pro-life, more pro-market and more anti-interventionist— but so do all reporters. Novak was different from the news-page reporters because he didn’t hide his opinions.

But the commentary in his columns was usually secondary. His aim in each column was to include at least one previously unreported fact. Sometimes it was a trivial tidbit. Sometimes it was a major scoop.

What did this mean in practice? It meant burning up the phone lines and wearing out some shoe leather.

Novak’s life as a columnist began in 1963 when he got a call from veteran journalist Rowland Evans. Evans was offered a six-times-a-week column by the New York Herald-Tribune, and as a condition for accepting it, Evans asked the paper to hire Novak as his partner. Evans’ strength was being an insider. He was a society man friendly with the Kennedys and from the same circles as those in power. Novak was something different. He had sleuthed the halls of the Capitol during his years with the Associated Press and the Wall Street Journal, prying lawmakers and staff for intelligence and keeping his ears peeled. It wasn’t too different 40 years later when I worked for him.

Novak kept an office half a block from the White House, with a staff of three. Kathleen, his assistant, spent most of her time as a scheduler. She was constantly getting congressmen, senators, White House staff, cabinet secretaries, agency heads and political operatives on the phone. At least a couple times a week, he had breakfast, lunch or a meeting with some politico or another. I almost never had the pleasure of sitting in on these meetings—Novak’s aim was always to make the source as comfortable as possible so that the source would talk.

Making people talk, listening well, remembering everything and following up were Novak’s real skills.

How did he do it? For one thing, he left the tape recorder in the office and the notepad in his back pocket. This sets your interlocutor at ease, making the meeting feel less like an interview and more like a conversation. For another thing, he operated, at almost all times, on background.

In journalism, there’s “on the record” and “off the record.” If you’re talking “on the record,” you can be named and quoted. “Off the record” information cannot be reported at all, unless the reporter gets an on-the-record source. “On background” is the large grey spectrum in between. Typically, Novak would talk to sources, promising only to vaguely identify them (such as “a senior administration official”) and often looking more for dirt than for quotes.

Most of the occasions during which I got to watch Novak work were in the Washington dinner-and-cocktail-party circuit. One educational moment came in a pre-dinner cocktail hour at the Willard Intercontinental Hotel in 2004. Ralph Reed approached us to talk to Novak. Reed was the former chairman of the Georgia Republican Party and was planning a run in 2006 for lieutenant governor.

After they greeted one another, Novak introduced Reed to me, and the two men traded pleasantries about the wife and kids, and then Novak asked Reed about Georgia politics. Reed gave some details and background on congressional races and 2006 statewide contests. I had been following some of these contests closely, and so I piped up with some of my insights. Soon, Novak subtly but definitively changed the topic from my insights back to Reed’s views on the political scene. I stood there blushing, but wiser.

As the conversation went on, I realized it was really an interview. Novak didn’t come across as an interrogator, but just an interested partner in a cocktail-hour chat. But he was collecting political intelligence—again, not for quotes or gotcha moments, but just intelligence. He simply wanted to understand better what was going on. While I was eager to share whatever wisdom I had collected, Novak gave his opinion only as much as he had to in order to extract more from the other person.

It’s a funny thing to say about a man with such strong opinions and immense self-confidence who was paid to give his opinions on national television, but Novak has always been far more interested in hearing what others had to say than in chiming in himself.

PUT NOT YOUR TRUST IN PRINCES

“Always love your country,” Novak loved to tell students when he spoke to them, “but never trust your government.”

For saying this, critics would sometimes accuse Novak of being a conspiracy theorist or chastise him for sewing cynicism among the young. Certainly in these days of “hope and change,” when such skepticism is low supply on most news pages, Novak’s words are needed direly.

Novak’s exhortation to “never trust your government” is not just a free-market rallying cry or a libertarian mantra. It’s also a pragmatic conclusion after years of witnessing in action the men and women who make our laws and regulations.

People who knew Novak in the 1960s—when he voted for Lyndon Johnson over Barry Goldwater, fearing Goldwater would move the Republican Party too far to the right—point out that he hasn’t always been as conservative as he is now. On the social issues, Novak’s late-life conversion to Catholicism helps explain his rightward shift. On economic issues and the size of government, his increasing conservatism is partly the result of his having a front-row seat at the sausage factories that are Capitol Hill and the executive branch.

Recently, a student asked Novak which politicians he admires. Novak paused, and thought—for a while. “Not very many at all,” he finally responded. Oklahoma Republican Tom Coburn has topped Novak’s list for the past two decades, and Novak actually penned a forward to Coburn’s 2003 book, “Breach of Trust.” But one day, walking down Pennsylvania Avenue back to our office, Novak told me about his model politician, William Purdy.

When Novak met Purdy in 1957 in Omaha, Neb., the cub AP reporter had little regard for the retired farmer. Novak wrote a profile of the freshman in the unicameral Nebraska Legislature, and it was not a flattering picture. Purdy, after giving up farming, ran on a few promises: He would serve only one term, he would give no floor speeches, he would propose no legislation and he would vote against every item that would increase taxes or government spending. Novak’s AP profile of Purdy was “as snide and dismissive as AP style would allow,” Novak wrote in his 2007 memoirs, “The Prince of Darkness.” Why was Novak so down on Purdy? It was symptomatic of a typical malady among legislative journalists—a malady Novak would, over the years, shake off entirely.

If your job is to cover what the legislature does, self-respect and ego compel you to believe that the legislature is very important. If a problem arises, the legislature should respond. You can see this bias in Novak’s recap of the 1957 legislative session in Omaha in which he assailed the state Legislature’s “striking lack of important legislation.”

This emphasis on “accomplishments” is a systemic bias among legislative or presidential correspondents. But when you stop covering just the debates and fights and start peeking behind the curtain, unearthing the intrigues and motivations behind the legislative process, it’s hard to maintain the romantic vision that republican lawmaking is a noble process. That’s why, today, Novak counts William Purdy as a hero and considers that unaccomplished 1957 unicameral session in which Purdy served a great success.

Novak shared with me the same disposition towards presidents. Most of the media judge presidents by some standard of “greatness” that amounts to: “How much did the man change the country?” Novak has a different standard, which involves living up to the oath of office and not messing up the country, which is why Calvin Coolidge is his favorite president.

One “great” president whom Novak dislikes immensely is Teddy Roosevelt. “If you go into a Republican congressman’s office,” he told me once, “you’ll probably see one of two portraits hanging on his wall: Thomas Jefferson or Teddy Roosevelt.” One problem with the Republicans, Novak argued, was the pro-TR leanings. Roosevelt believed in using his White House perch to intervene both in the U.S. economy and abroad. Teddy Roosevelt believed in himself and was willing to wield whatever power he could get his hands on.

We’ve seen plenty of Roosevelt Republicans in recent years trying to use Congress, the tax code and our military to craft a better world. The fruits of this have been ballooning deficits, spending increases under Republican government and, finally, Democratic control of all branches.

“Remember,” Novak was sure to remind me. “Roosevelt coined the word ‘muckraker’ as a term of derogation.” Those in power, he said, really do resent as troublemakers those who critique, expose and question their grand plans.

THE PLAME AFFAIR

It’s unfortunate that any account of Novak’s career has to include Joe Wilson and Valerie Plame, but it’s a fact. And I suppose I owe the reader my account of the whole affair because I was there—sort of.

On the summer day when Novak’s assistant Kathleen scheduled the interview with Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage, I was probably in the office. Around Novak’s office, we used to get excited about talk of Armitage or when he appeared on our television sets, because he bore an uncanny resemblance to a CNN producer who was a favorite in the office, Bob Kovach. But aside from that, nothing about an Armitage-Novak meeting piqued my interest. (I didn’t know that Armitage had been denying Novak interview requests for two-and-a-half years.)

Like Novak, I had opposed the Iraq invasion. But also like Novak, I suspected the late-arriving Democratic critics of the invasion of acting in bad faith for political gain alone. So when former Ambassador Joe Wilson penned an op-ed in the Sunday, July 6, 2003, New York Times titled “What I Didn’t Find in Africa,” further hammering home the notion that the Bush administration was off-base to claim Saddam Hussein was on the verge of attaining nuclear weapons, his account seemed likely to me—but the liberal celebration of Wilson and his column made me wince.

The next day, when Novak actually went over to the State Department to sit down with Armitage, I was also in the office. But I didn’t notice anything about it—I didn’t notice his calls with Ambassador Wilson or President George W. Bush’s special assistant Karl Rove. I was busy writing two issues of the Evans- Novak Political Report so that things would be in place for my upcoming two-week trip to Ireland—my first and only true vacation during my three years in Novak’s office.

I was there Tuesday, July 8, when Novak filed the first column to come out of the Armitage meeting, about appointee Frances Fragos Townsend. It was on this topic of Townsend’s liberal Democratic past that Novak called Karl Rove—the conversation in which Novak, as an aside, also asked for and received confirmation that a certain ambassador’s CIA wife had secured the ambassador a mission to Niger.

But on Friday, July 11, when Novak wrote and filed the fateful column about Joe Wilson, mentioning Wilson’s wife, I was in a pub in Dublin, Ireland, just off the cricket pitch on the campus of Trinity College. When the column ran on Monday, July 14, I was driving a left-hand-shifting manual-transmission car through the hilly and crowded streets of Tipperary. That column’s sixth paragraph read:

“Wilson never worked for the CIA, but his wife, Valerie Plame, is an Agency operative on weapons of mass destruction. Two senior administration officials told me Wilson’s wife suggested sending him to Niger to investigate the Italian report. The CIA says its counter-proliferation officials selected Wilson and asked his wife to contact him. ‘I will not answer any question about my wife,’ Wilson told me.”

Today, we know those “two senior administration officials” were Armitage and Rove. When Novak wrote, “The CIA says,” he was referring to his conversation with CIA spokesman Bill Harlow.

It was weeks before a real uproar ensued. That is when the Washington Post revealed that the FBI was investigating whether anyone broke the law in telling Novak the fact about Wilson’s wife.

For months, the big question was “Who told Bob Novak?” Novak never told me, and I never asked. But I spent plenty of time speculating. From his Oct. 3 column, in which he wrote his source was “no partisan gunslinger,” I had two top suspects: Armitage and Secretary of State Colin Powell. But in late September, Armitage had spoken at an off-the-record Evans-Novak Political Forum hosted by Novak for paying attendees. I thought it was unlikely Armitage would have shown up had he been the cause of the whole uproar. So, until it all came out years later, I had thought Powell was the guy.

This story was overplayed in the media—probably because it fed the widespread Bush-and-Cheney-are-criminals mania, but also because it involved the media itself—so I won’t rehash the well-worn details.

But being at the scene, I know there were some interesting details missed by the media swarm. First was the absurdity of the odd line that even if Novak found Wilson’s wife’s employment relevant enough to report, he shouldn’t have reported her name. The irony is that he didn’t really report her name—he reported her maiden name, which his staff researcher found in Wilson’s entry in “Who’s Who in America.” But “Who’s Who” lists entrants’ wives by their maiden name (for example Elizabeth Dole is listed as “Elizabeth Hanford”). Valerie hadn’t gone by “Plame” since her marriage, and many of her neighbors knew her only as Valerie Wilson.

So, writing “Joe Wilson’s wife” would not only have obscured her identity from those without access to “Who’s Who,” but also, Novak may have permanently changed this woman’s name from Wilson back to Plame.

Of course, the lasting impact on Novak of this incident was added vitriol from the Left. Liberal journalists and politicians unthinkingly or dishonestly advanced the idea that Novak had been an accomplice to the White House in outing Plame as revenge for Wilson’s critiques of the Iraq War. Of course, both Novak and Armitage opposed the Iraq invasion and distrusted Bush’s claims of Iraqi WMDs, taking most of the air out of that argument. But when it comes to maligning public figures whose views are at odds with your own, most commentators, bloggers and politicians have little room for details.

LEARNING A LESSON

In 2009, for the first time in decades, Novak didn’t host an inauguration party. He was too ill. While the brain tumor with which he was diagnosed in July has been well-contained by surgery, chemotherapy and radiation treatment, the whole process has left him utterly exhausted. At this writing, Novak is in physical therapy, gaining back his strength.

But I thought of Novak during President Barack Obama’s inaugural address. “Now, there are some who question the scale of our ambitions,” the president intoned, “who suggest that our system cannot tolerate too many big plans.” Obama dismissed these doubters as “cynics” with “short memories.”

In these days of “hope and change,” you can get in trouble for doubting the wisdom of Big Government. Questioning the ability of bright, well-intentioned politicians and public servants to make our lives better is assailed as “hoping for failure” or, if the doubter is a Republican, as being a sore loser.

Our Hollywood celebrities are reciting pledges to serve our new president and enlisting the masses to follow. MSNBC anchor Chris Matthews has declared it his job to make sure the president succeeds. Leaders of the congressional majority are circulating a petition denouncing Rush Limbaugh because he said he hopes Obama fails. This same majority is agitating for a Fairness Doctrine regulation that would silence many critics.

In the minds of our elites, dissent, once patriotic, is now sedition.

At this time, more than ever, Novak’s example is needed. Dogged contrarianism and skepticism is the needed attitude. Actual reporting is the needed work. And Novak’s long career is the needed inspiration.