Do you remember the 1957-58 Asian flu? Or the 1968-69 Hong Kong flu? I do. I was a teenager during the first of these, an adult finishing law school during the second. But even though back then I followed the news much more than the average person my age, I can't dredge up more than the dimmest memory of either.

I don't have any memory of schools closing, though apparently, a few did here and there. I have no memories of city or state lockdowns, of closed offices and factories and department stores, of people banned from parks and beaches.

Yet these two influenzas had death tolls roughly comparable to that of COVID-19. Between 70,000 and 116,000 people in the U.S. died from Asian flu. That's between 0.04 percent and 0.07 percent of the nation's population, somewhat more than the 0.03 percent of the COVID-19 death rate so far.

The Asian flu, unlike COVID-19, was rarely fatal for children and was more deadly for the elderly -- and pregnant women.

The Hong Kong flu, the Center for Disease Control & Prevention says, had more precisely an estimated U.S. death toll of 100,000 in 1968-70 (years that included the Woodstock festival), 0.05 percent of the total population. Both flus had high death rates among the elderly but, apparently, not as high a proportion as COVID-19 has had.

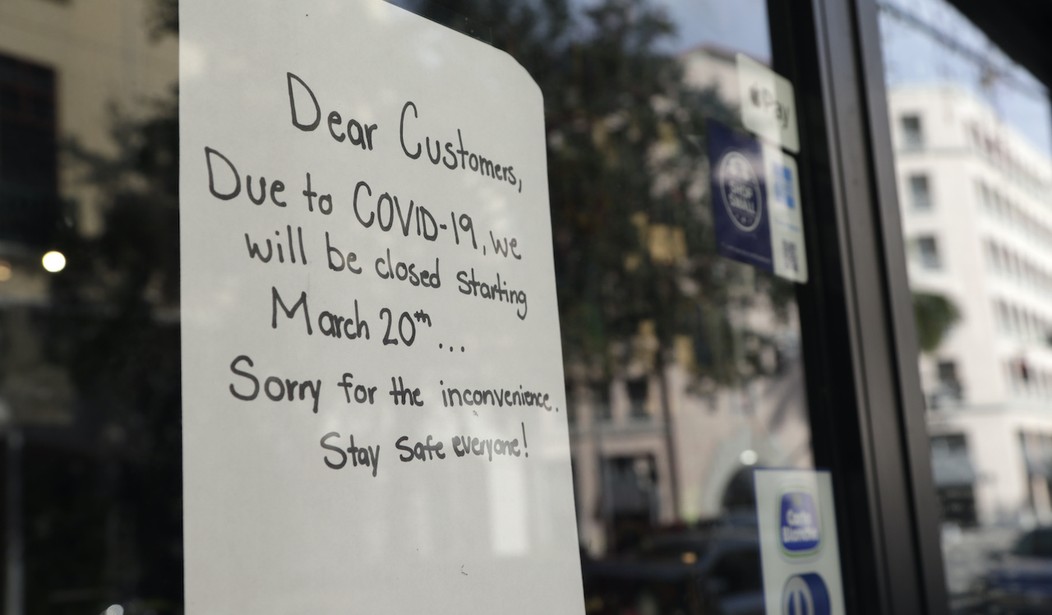

Once again, there were no nationwide school closings, no multi-month lockdowns, no daily presidential news conferences. Apparently, neither the nation's leaders nor the vast bulk of its people felt that such drastic measures were called for.

Perhaps some of this calm reaction can be ascribed to confidence that a vaccine would be developed, as other flu vaccines had been developed after the 1918-19 Spanish flu pandemic. But flu vaccines are never entirely effective, and none were widely available until after the Asian and Hong Kong flus had swept over the nation.

Recommended

Fundamental attitudes can change in a nation over half a century, and the very different responses to this year's coronavirus pandemic and the influenzas of 50 and 60 years ago suggest that Americans today are much more risk-averse, much more willing to undergo massive inconvenience and disruption to avoid marginal increases in fatal risk.

At least some of this can be explained by different experiences. The Asian and Hong Kong flus arrived in an America amid and at the end of what I call the Midcentury Moment. That's my name for the quarter-century after World War II when Americans enjoyed low-inflation economic growth, and a degree of cultural uniformity and respect for institutions that some yearn for today.

Midcentury Americans had living memories of World War II, with its 405,000 American military deaths. They were troubled not so much by the number of military deaths in Korea (36,000) and Vietnam (58,000) but by our leaders' failure, after years of effort, to achieve victory.

Contrast this with the shrillness of outcries over orders of magnitude fewer military deaths in Iraq (4,497) and Afghanistan (2,216). Yes, every death is a tragedy, but those numbers total less than the average number of deaths in America every day (7,707) in 2018. But today's Americans, beneficiaries of a victory in the Cold War that was almost entirely bloodless, seem to blanch at paying any human price.

They seem to also expect any competent leader to come up with policies that preserve every life at any cost. Thus the high approval of New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who said his lockdown is worth it if it saves just one life -- although if he really believed that, he'd impose and strictly enforce a five mph speed limit on the New York State Thruway.

You can argue that Americans in the Midcentury Moment were too willing to accept pandemic or battlefield deaths, just as they were too willing to accept racial segregation or to stigmatize uncommon lifestyles.

But there's also a strong argument that they had a more realistic sense of the limits of the human condition and the efficacy of official action than Americans have today -- certainly more than the governors stubbornly enforcing lockdowns till the virus is stamped out and deaths fall to zero.

Behind that stance is the assumption there's an instant and painless solution for every problem, rather than a need to weigh conflicting goals and make tragic choices amid unavoidable uncertainty.

Michael Barone is a senior political analyst for the Washington Examiner, resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and longtime co-author of The Almanac of American Politics.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member