My goal in life is very simple. I want to promote freedom and prosperity by limiting the size and scope of government.

That seems like a foolish and impossible mission, perhaps best suited for Don Quixote. After all, what hope is there of overcoming the politicians, interest groups, bureaucrats, and lobbyists who benefit from bigger government?

But I don’t think I’m being totally irrational. I’ve pointed out, for instance, that we can make progress if we simply restrain the growth of government so that it expands slower than the private sector. Surely that’s not asking too much, right? Heck, we’ve done that for the past two years!

Moreover, while much of Washington is a fact-free zone, I’m encouraged by the wealth of evidence showing that big government is bad for growth.

I’ve cited research on the negative impact of excessive government spending from international bureaucracies such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and European Central Bank. And since most of those organizations lean to the left, these results should be particularly persuasive.

Recommended

I’ve also cited the work of scholars from all over the world, including the United States, Finland,Australia, Sweden, Italy, and the United Kingdom.

I’ve also cited the work of scholars from all over the world, including the United States, Finland,Australia, Sweden, Italy, and the United Kingdom.

And I share additional compelling data in this video, including a comparison of the United States and Europe.

Now we have some more evidence to add to our collection. Here are some excerpts from a study by two European economists. We’ll start with a blurb from the abstract that tells you everything you need to know.

The aim of this paper is to analyze the impact of government spending on the private sector, assessing the existence of crowding-out versus crowding-in effects. Using a panel of 145 countries from 1960 to 2007, the results suggest that government spending produces important crowding-out effects, by negatively affecting both private consumption and investment.

But if you want to understand how they did their research, here are some methodological details.

While most of the tests of the “crowding-out” versus “crowding-in” hypothesis that have been carried in previous papers focus on a time series or cross-country approach, this work extends such analysis to a panel data set of 145 countries from 1960 to 2007. The results show that government spending produces important crowding-out effects, by negatively affecting both private consumption and investment. …In addition, we analyze possible asymmetries of the effect of government consumption on private consumption and investment. In particular, we test: i) whether the effect varies among regions; and ii) whether it depends on to the phase of the economic cycle. We find that the effect varies substantially among regions, but it does not seem to depend on the phase of the economic cycle. …we study the impact of changes in the ratio of government spending to GDP on the growth of real per capita private consumption and private investment.

Here are some of the key results, starting with how government spending impacts consumption.

Starting with the analysis of the effect of government consumption on private consumption (Table 5a), we can immediately see that it is negative and statistically significant. The results also suggest that not only contemporaneous changes in the government consumption-GDP ratio matter, but also its past lags (specifically, the 2nd and 3rd ones). In particular, the cumulative effect of government spending on private consumption is about 1.9 %, of which about 1.2% captured by contemporaneous changes in the government consumption-GDP ratio and 0.7 % by its lags. This result can be interpreted as follows: an increase of government consumption by 1 % of real GDP immediately reduces consumption by approximately 1.2%, with the decline continuing for about four years when the cumulative decrease in consumption has reached approximately 1.9 %.

And here’s the data on how government spending affects investment.

Similarly to what we obtained for private consumption, both current and lagged changes in government consumption-GDP ratio have a negative and significant effect on private investment, with a cumulative effect of approximately 1.8%. The main difference between the effect on consumption and investment is that, while contemporaneous change in the government consumption-GDP ratio seems to have a bigger effect on consumption, lagged changes are more detrimental for investment.

Interestingly, the economists find that the harmful impact of government spending varies by region and country.

But is the effect similar for different regions and countries? To answer this question, we replicate the estimations for specific geographical areas and countries. …The results show that the effect varies substantially between areas. In particular, while we find statistically significant crowding-out effects in Africa, Europe and South America, government spending does not seem to have (statically) significant affects in the other areas considered. We also assess whether the effect is different between developed (OECD) and developing countries. The results suggest that the impact of government spending on both private consumption and investment is more detrimental in the OECD group. …it emerges that the “crowding-out” effects of government consumption are largest in relatively less developed countries (such as Mexico and Turkey) and in those countries with a high share of government spending (such as Finland, Sweden and Norway).

While I’m always cautious about drawing sweeping conclusions from any single piece of empirical research, these results make a lot of sense.

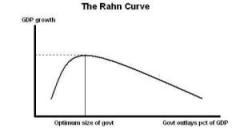

The Rahn Curve (which is sort of a spending version of the Laffer Curve) is based on the theory that a very modest level of government, focusing on providing core public goods, is associated with better economic performance. But once government gets too big, than the relationship is reversed and higher levels of spending are associated with weaker performance.

The Rahn Curve (which is sort of a spending version of the Laffer Curve) is based on the theory that a very modest level of government, focusing on providing core public goods, is associated with better economic performance. But once government gets too big, than the relationship is reversed and higher levels of spending are associated with weaker performance.

So it’s no surprise that bigger government has particularly bad effects in nations that already have bloated public sectors. Here’s the video I narrated on the Rahn Curve, which provides additional analysis.

Last but not least, it also makes sense that bigger government has a pronounced negative effect in less-developed nations. Those are countries that generally have serious problems with corruption, cronyism, and the rule of law (i.e., Argentina), so the budget often is simply a tool for transferring funds to those with power and political connections.

For all their flaws, the Nordic nations at least are reasonably honest and well run. That being said, the fact that they can endure a larger level of government doesn’t mean it’s a good idea.

P.S. Someone did a video attacking my analysis of the Rahn Curve. Except it isn’t really an attack since I agree with the criticism.

P.P.S. For those who want to argue that the relative prosperity (by global standards) of Western Europe is evidence that big government is good for growth, I invite you to look at this chart. Simply stated, Western Europe became rich when government was very small.

P.P.P.S. Just as there’s lots of evidence about the damaging impact of government spending, there’s also a lot of research showing that high tax rates are economically destructive.

P.P.P.P.S. While I sometimes myopically focus on fiscal policy, remember that there are many other policies that determine economic performance.